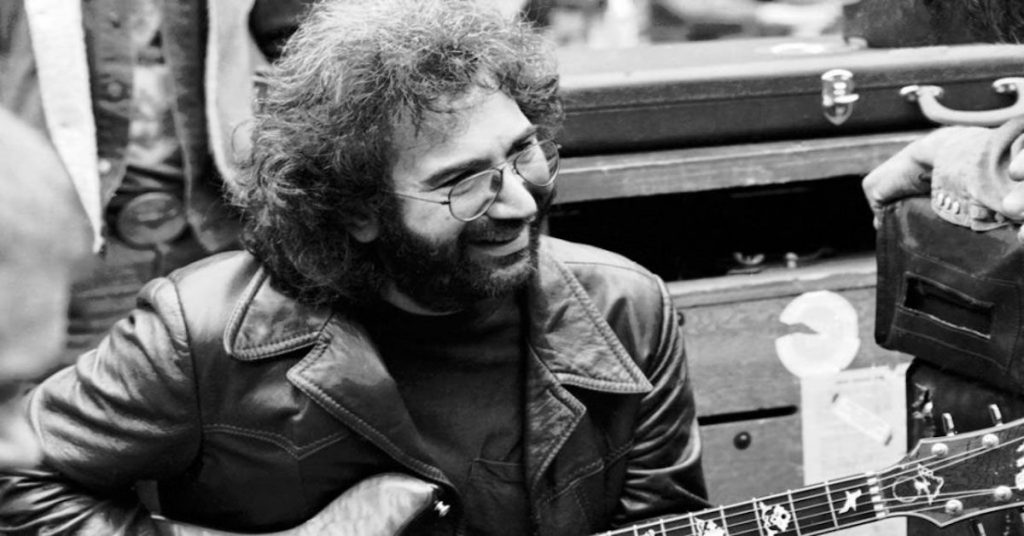

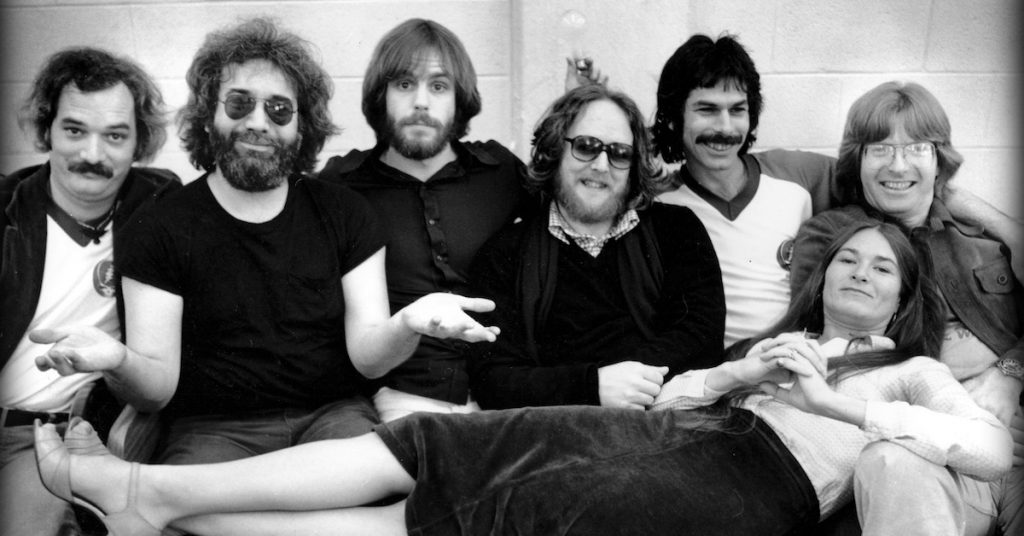

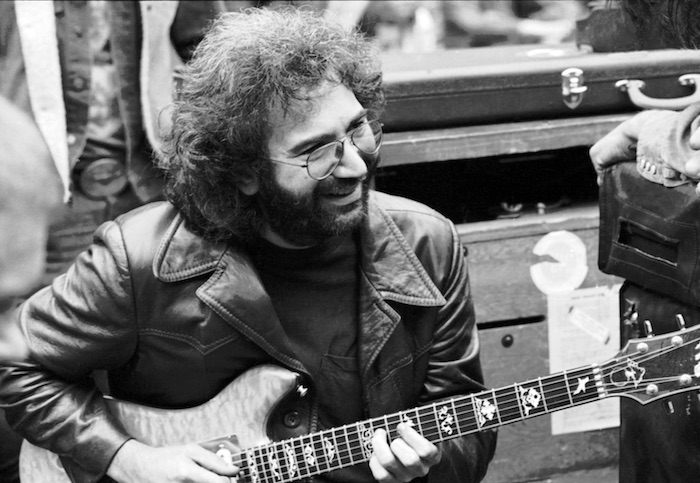

Back in 1976, this writer conducted a two-hour interview with Dead guitarist/singer/songwriter Jerry Garcia, at music promoter/producer Bill Graham’s house in Mill Valley, Calif. Garcia—who died on 1995 at age 53—was very accessible, showing an interest in me as well as discussing his own music and life. He wanted to know what music I dug, which books I had read, the kind of comics I collected. Garcia was born August 1, 1942.

“I met Jerry in 1965,” Graham (who died in a helicopter crash in 1991) told me about his own relationship with Garcia. “I thought he and his entire band were from another planet. I got to know him later on [but] there are times when I still really think the Grateful Dead are demented. Insane.”

The following is an excerpt from my Garcia interview from that day in 1976.

You and the Dead have helped create an ongoing music community and scene. When did you first notice that the Bay Area bands were starting to make an impact in other places?

Jerry Garcia: I really think the scene out here created the possibility for Woodstock to happen, [like] the Monterey International Pop Festival. The thing—the activity, music and people—the setup was out here.

In a business marked by one-hit wonders and trends, how do you account for your longevity?

We’re serious. One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike. I think each of us has dealt with it in various ways. Like, Carlos [Santana] has developed himself into a spiritual being from a completely different kind of person. For me, I know what I’m supposed to do, and I’ll do what I have to do to be able to play. I think almost all the people I’ve known around this area, involved around the music scene, have been faithful to that thing.

Watch the Grateful Dead perform Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away” in New York in 1976

Was there any added pressure, being a mouthpiece for the community?

Everybody knows who they are. No matter what you read about yourself in the paper, you know who you are. You don’t get any special breaks at the gas station. You can either be sucked in by that stuff, in which case it just eats you, or else just realize there’s a difference between what you read and who you are.

Did you ever feel you represented something special to the honest music community?

I always did. I think that the world has changed. I think the United States has changed very visibly in the last 10 years. A lot of it had to do with what happened in San Francisco. I can’t say how or why, but I also think it’s affected everything?

Like how?

Just all the interest in things like ecology. All the interest in the sense of personal freedom as expressed by all kinds of movements. All these things were designed to free the human. Social overtones, all that stuff. The communal spirit.

Related: One of our favorite clips, David Letterman teaching Garcia how to play “Proud Mary”

Have you always liked playing live? You strike me as a workaholic.

I like the live experience. That’s where it counts. That’s when music is real. It’s real in that situation. That’s the situation that I feel I have the greatest sense of personal responsibility about. I don’t mind putting out a bad record, but I really hate a bad concert. That really is depressing.

Listen to the Dead perform “Sugaree” from the Fox Theatre in St. Louis in 1971

You get into other musical avenues with solo projects away from the Grateful Dead. Has there ever been any conflict or compromise in doing a tune for the Dead or keeping it for future solo endeavors?

It’s not judgmental. You can’t deal with it in a yes/no kind of fashion. For example, my [solo] band could best be described as consonance and harmony. Conceptually, everybody in the band thinks pretty similarity. In the Grateful Dead, it’s a situation in which almost no two people have the same conception musically, which makes it harder. Nobody gets their way. However, what we all respect about that situation is that there is a potential of a larger central viewpoint which none of us, individually, are capable of perceiving, but which we all add to because of the diversity and the conflict.

Did you ever think, 10 years ago, that the Grateful Dead would get beyond the ballroom circuit and that rock and roll would be presented in baseball stadiums?

When the Acid Tests were happening, I personally felt, “In three months from now the whole world will be involved in this.” So, as far as I’m concerned, it’s been slow and disappointing. Why isn’t this paradise already? (laughs). My personal feeling has been one of waiting around.

Watch and listen to rare footage of the Dead at the 1966 “Acid Test Graduation Ceremony”

Being an elder statesman in the rock and roll world, how long do you feel you can continue the hectic pace?

I’ve learned that it requires a certain discipline for me personally. And I know I’ll approach it in a certain way. I’ll definitely burn out. For me, it’s a matter of surviving. This is the set of givens. You’re gonna be in airports, motels, exposed to any number of strange drugs, strange experiences, intensity of this sort, and so forth. Within that framework how do you stay even? What you do is learn so it becomes a thing of pace, vitamin C, protein. You try and stay alive. That’s a fundamental problem. I’m just the sort of person who deals with things on that level. Once I know things I have to cope with, it’s just a matter of adjustment. I just hate personal failure, being on stage and going through the changes and playing bad, because I’m either not well, tired, too stoned, whatever. To me it’s an aversion therapy thing. It’s the reason I’ve been able to survive.

Do you have high and low points that you best remember, looking back over the last 10 years?

Well, I can get into that real easy. The worst for us, and for me personally, was Woodstock. The ultimate calamity. First of all, we were really stupid in the way we dealt with it. It was raining and we went on just after it got dark. There was maximum confusion going on. Really weird. Plus, I was high, of course. And I went on stage in a state of confusion. Huge crowds of people over the stage. The stage had sheet metal and stuff on it, it’s wet, and I’m getting incredible shocks from my guitar. Pretty soon I started hallucinating a ball of electricity rolling across the stage, jumping off my guitar. Meanwhile, [there were] all these little citizen band radios and walkie talkies so there’s weird voices coming out of the amplifiers. It’s dark, and you don’t see any audience, but you know there are 400,000 people out there. Then somebody leans over across the stage, since everyone is ganged up, and says the stage is about to collapse. I’m standing there in the middle of this trying to play music. Then they turn on the lights, and the lights are a mile away. Totally blinding, and you can’t see anything at all. Here’s this energy and everything is horribly out of tune, ’cause it’s all wet, damp and humid. It was just a disaster. It was humbling (laughs).

Watch part of the Grateful Dead’s set at the 1969 Woodstock festival

Related: Rolling With Jerry: When Garcia welcomed a college kid to the Dead’s HQ

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

1 Comment

That may well be one of the most illuminating paragraphs I’ve ever read about the Woodstock experience from a performer’s viewpoint. Amazing!