It’s one of the iconic opening lines in rock music, set against one of its most distinctive riffs, the listener’s introduction to the world of Jethro Tull’s Aqualung, released in the U.K. on March 19, 1971 (and May 3 in the U.S.).

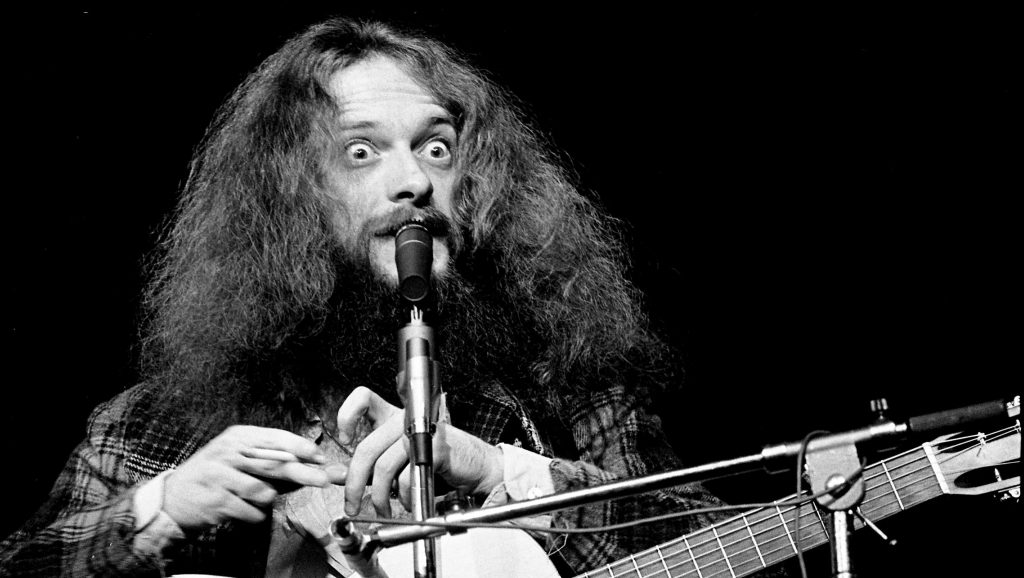

On Aqualung, Jethro Tull demonstrated the full range of their talents, infusing songs with hard rock, classical and progressive elements. Whether in brief ditties or multi-part epics, singer/songwriter/flutist Ian Anderson and the band introduce us to outcasts, sinners and those left behind, while delivering a harsh critique against societal constructs. It’s an ambitious album, one that remains relevant, timeless and infinitely accessible. In the world of progressive rock, that’s no simple feat.

The Blackpool-based band Jethro Tull had made a name for themselves mainly with blues-rock stylings on This Was (1968), Stand Up (1969) and Benefit (1970). But by the time work started on Aqualung they’d be revitalized: heavier, more insistent and even more compelling.

Aqualung features Anderson on his distinctive flute, acoustic guitar and vocals; Martin Barre on electric guitar; and Clive Bunker on drums and percussion for what would be his final album with the band. Rounding out the lineup were newer recruits John Evan on keyboards and Jeffrey Hammond, who learned how to play bass while in the process of joining the band at the tail end of 1970. They set up in Island Studios on Basing Street, London, to record an album with a theme.

As Anderson recalled, the band was essentially guinea pigs in the new space, working with brand new equipment that no one seemed to have been trained in. As it turned out, Led Zeppelin had booked the smaller, less lively sounding space in the studio complex to make Led Zeppelin IV so Jethro Tull was left with a cavernous converted church better suited for orchestral recordings, giving the album a distinct sonic fingerprint. Though the album’s creation may not have been easy, the effortlessness of Jethro Tull’s musicianship and the excellent material shone through on this landmark album.

Side one explores the role of misfits and the systems that cast them aside. It opens with the ultimate vagrant’s tale: “Aqualung.” Here, we get glimpses of an unsavory and disheveled tramp, greasy, unwanted, casting glances at girls, all against some of the best rock Tull ever laid down. But the mood switches in the B-section, where Anderson uses the moment to introduce an element of pathos: “Aqualung, my friend, don’t you start away uneasy,” the narrator directs. “You poor old sod, you see it’s only me.”

The contrast between the tramp’s socially unacceptable behavior and the descriptions of his condition—his “leg hurting bad as he bends to pick a dog-end” and his reliance on the Salvation Army for comfort—is mirrored by the musical complexity. Anderson’s vocals are at once grisly and howling, then delicate and soft. Meanwhile, the band channels heavy rock, with Barre delivering searing riffs and solos. They point to their blues roots, then alternate to folksy intimacy. That’s not to mention the stark contrast between heavy rock instrumentation and Anderson’s flute. As an opener, it’s an introduction to the revitalized Jethro Tull, to their story-based songs, and to the themes that would carry on through the album. That’s made evident by another misfit’s story set to hard rock, “Cross-Eyed Mary,” whom Anderson described as a woman who “was willing do the things the nice girls wouldn’t…Aqualung’s pal.”

The middle of the first side presents a more stripped-down sound, influenced by the likes of Scottish folk and singer-songwriter styles. “We had some good models as songwriters around us,” Anderson recalled in 2011. From Simon and Garfunkel and Bob Dylan to acoustic guitarist Bert Jansch and “the whimsical and slightly philosophical Roy Harper,” Anderson was interested in “a kind of purity and a simple clarity of approach.”

Watch Tull perform “Cross-Eyed Mary” live at the Capital Center, Landover, MD, November 21, 1977

The brief “Cheap Day Return,” clocking in at just over a minute, shows off Jansch-like guitar figures, along with complementary orchestrations by Dee Palmer. “[It’s] about a day I went to visit my father in hospital in Blackpool,” said Anderson in 1971. “I caught a train at nine, spent four hours traveling, four hours with my father, and four hours to get back again. It was a long song mainly concerned with the railway journey, but the section on the record is about visiting my father. It’s a true song.” The lilting, Scottish-influenced “Mother Goose,” with its layered recorder lines and alternating time signatures, is pure surrealism. Bearded ladies, chicken-fanciers, elephants in Piccadilly Circus and scarecrows stealing from snowmen all make an appearance in the jaunty, Medieval-inspired tale.

Related: Our Album Rewind of another Tull concept album, Thick As a Brick

It’s followed by perhaps the most personal song on the album, a love ballad called “Wond’ring Aloud.” “We are our own saviors as we start both our hearts beating life into each other,” Anderson sings against his acoustic strumming, punctuated by orchestral swells and the occasional weaving piano line. The song was originally recorded as a seven-minute epic, leftover pieces of which can be heard on “Wond’ring Again” on the 1972 compilation album Living in the Past. A complete alternate version of the suite turned up as “Wond’ring Aloud, Again” on a 2011 expanded reissue of Aqualung. You can listen to it below.

Listen to “Wond’ring Aloud, Again” (Full Morgan Version) (Steven Wilson Stereo Remix)

The side closes with “Up To Me.” It’s a riff-heavy blues-rock burner featuring winding electric guitar leads against Anderson’s gentle acoustic guitar and snaky flute lines, a perfect contrast to the breezier songs that precede it and a primer for the heavier material to come.

Side two is centered around the theme “My God,” which is also the name of the first song on the side. It’s a slow-building and dramatic rock number critiquing organized religion, complete with a choir interlude. “It’s a lament for God,” said Anderson in a February 1971 interview. “Really within myself I’m referring back to the kind of ideas of God and religion with which I was brought up. In the context which I knew it, God is a highly personal thing, a feeling of righteousness and goodness.”

This was a bold move for a British band in 1971. Anderson knew he was likely to offend with lines like, “So lean upon him gently/and don’t call on him to save/you from your social graces/and the sins you used to waive,” not to mention “And the bloody church of England/in chains of history/requests your earthly presence/at the vicarage for tea.” But Anderson also stressed that his concern wasn’t with God or spirituality, but with the systems of authority that have used a relationship to a god “as an excuse” for inhumane behavior. “I wouldn’t want to take people away from God,” he told Disc & Music Echo ahead of the album’s release. “In fact, I don’t think you can get any further away from God than we are today.”

Listen to “My God” live at Palais des Sports, Paris, July 5, 1975

He continues to explore the theme with “Hymn 43,” a driving, gospel-tinged number that asks God for forgiveness for what man has done to Him. “If Jesus saves, well He’d better save Himself,” Anderson howls over Barre’s licks and John Evan’s frantic piano, “from the gory glory seekers who use His name in death!”

Then, on “Locomotive Breath,” Anderson takes stock of a different sort of impending doom. Thematically, the song deals with the dread of survival in a world that’s gone off the rails due to greed and corruption, personified as a runaway train. In 1971, Anderson could see the effects of technological advancement, social systems and a growing world outpacing itself, declaring in its refrain that there was “no way to slow down.”

“We’re still there,” he told a reporter in 2011. “We’re making a much more difficult habitat in terms of food and water and the quality of air we breathe, as people continue to take resources without a longer-term plan.” That danger is represented musically by the song’s dramatic builds. It begins with a declarative piano introduction, before transitioning into a blues vamp, then into that distinctive minor-keyed riff that carries Anderson’s frantic, yelped singing. The band is locked-in, with a driving, metronomic rhythm, yet it feels like it could speed off the rails at any point. But, like many other songs on the album, it fades out, leaving you to wonder if the intensity ever boiled over.

The closing track, “Wind Up,” is the culmination of all the ideas that had run thorough the album so far, but more directly a condemnation of organized religion as a charade and its influence on youth. As Anderson recalled in a February 1971 interview, “[My parents] sent me to Sunday school when I was young but I rebelled after the first visit and I was never forced back. I think my parents are the exception, though, and there is so much religion today forced onto children simply by virtue of their parents’ race or creed—and that in itself is inherently wrong.” Here, he describes religion as an action done to erase sins, something that becomes a performative ritual, but is never truly embraced as a pathway to enlightenment. “To me, religion is something that you grow up to find in your own way,” he said to NME in March 1971. “I am sure that a lot of other people believe in God the same as I do, that faith is a form of goodness around which you relate your life.”

Watch “Wind Up” live at the Capital Center, Landover, MD, November 21, 1977

These declarations did draw attention from those who felt rock was already a godless form and a bad influence on the youth. But Anderson defended himself, saying, “I am basically a religious person—I believe in the God concept for the individual and most of the songs on the album [are] pro-God. There are really no anti-God songs on the album.”

Ultimately, Aqualung proved successful, with the rock press heralding the album for its variety, seriousness and the unmatched musicianship. “Hymn 43” was selected as a single but only grazed the Top 100 singles chart. The album, however, was a worldwide success, reaching the top 5 in eight countries, peaking at #7 in the U.S. and #4 in the U.K. Since its release, the album has sold more than seven million copies and its songs have become FM radio staples.

Related: 1971, the year in rock

The acclaim brought the band its first real taste of stardom, and launched it into its next phase as prog-rock juggernauts. But Anderson is adamant that, despite its status, Aqualung is not your usual concept album. It may seem counterintuitive, especially as the band went on to make some of the most acclaimed examples of the genre, but it’s clear why Anderson feels that way about Aqualung. The canonical concept album includes one overarching story to draw in the listener. Too often, the concept bogs down the quality of the music as more and more subplots emerge, musical themes and variations play out and general audiences lose interest. Not so with Aqualung. Sure, there are stories and characters, and thematic threads are woven throughout, but the songs also exist perfectly on their own without an overarching story line.

In a 2016 interview, Anderson was asked why he was eager to write what he called his “adolescent emotions.” He replied, “I was worried I’d grow out of them.” Yet 50 years on, he still believes in the messages behind Aqualung. “It isn’t nostalgia for me…It still feels important.” Those universal, even prophetic themes of security, loss, spirituality and struggles with authority not only resonate with the front-man, but also with fans and newcomers—even all these years later. Indeed, on Aqualung, Anderson, Barre, Bunker, Hammond and Evan managed to rise to the occasion to create a true classic—an album that challenged convention and helped establish rock music as an art form—concept album or not.

Watch Jethro Tull perform “Aqualung” live on Rockpop In Concert in 1982

See Jethro Tull in concert. Tickets are available here and here. Tull’s vast catalog is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Related: 1971—The Year in 50 Classic Rock Albums

- Jethro Tull—’Aqualung’: The Ultimate Concept Album - 05/03/2024

- The Who’s ‘Face Dances’: After Tragedy, Transition - 03/16/2024

- Steely Dan Delivers Bite-Sized Gems on ‘Pretzel Logic’ - 03/02/2024

9 Comments

My very first concert courtesy of my older brother. And what a show/experience!

Music notwithstanding, I have always felt Anderson’s talents as a poet/lyricist don’t get as much praise. To be in his young 20’s writing these lyrics (and those to follow) is remarkable, to me anyway.

For me located in germany jethro tull was first considered as a hard rock band. the song locomotive breath was heavily played at school parties during my childhood.

Too true, Aqualung. Anderson’s lyrics, especially combined with his melodies, are quite remarkable, showing a level of intelligence, wit and ultimately, musicality that are incredible, to the point of amounting to an isolated incident of genius to be found in one package. What’s equally amazing is that he’s been able to find the crack musicians to aptly bring his visions to life, with such precision, over and over again over the years. At this point, I have absolutely no respect for the so-called “R&R Hall Of Fame,” and if you needed just one prime example of why it’s name and it’s actual operating premise are so misaligned, you could very easily cite the fact that Jethro Tull was not recognized by it for inclusion years ago, and hasn’t still.

Aqualung is not a concept album, as Ian Anderson has noted on multiple occasions. Thick As A Brick and Passion Play are concept albums and of the highest order.

Ian says it’s not a concept album, but it certainly has a lot of songs dealing with god and religion, which was unusual for rock albums at the time. Aqualung used to be my favorite album, and it’s still one of my favorites, but now I may like A Passion Play even better. This week I’m releasing my own album, A Pastiche Play, which is a collection of 12 original progressive rock songs joined into one long musical piece like on A Passion Play.

Interesting, I’ve always thought Passion Play was the most unique album ever made by this most unique band. Unique squared if you will. The band members don’t like it, but Tull fans like me view it as a seminal album along with Aqualung.

Ian Anderson has been very clear over the years that Aqualung is NOT a concept album at all. In fact, he wrote the next album, Thick as a Brick, as a parody of concept albums after reading reviews of Aqualung that thought it was one.

Aqualung was a collection of songs, not a concept album. Ian Anderson did not agree with critics who called it a concept album, and JTs next album was a concept album in response. The title, Thick as a Brick, captures what Ian thought of critics calling Aqualung a concept album.

I have fond memories of Aqualung resonating through the woods at night from a portable 8 track player, camping and drinking beer with friends. I always felt a cohesiveness of concept in the entire experience. Definitely a concept album, despite the naysayers, including Mr Anderson.