Nearly five decades later, someone’s still missing the point. When it comes to Jethro Tull’s seminal Thick as a Brick, it might be the listeners who fail to see its underlying nature, thinking it a developmental milestone for progressive rock rather than a parody of its excesses. On the other hand, it might be the album’s composer and lyricist, Tull frontman Ian Anderson, who, in his attempt to tweak a genre he considered too self-important, didn’t recognize that employing elliptical poetic bluster as a send-up of art that thrives on the overblown ultimately is just grabbing another tool from the same kit.

Nearly five decades later, someone’s still missing the point. When it comes to Jethro Tull’s seminal Thick as a Brick, it might be the listeners who fail to see its underlying nature, thinking it a developmental milestone for progressive rock rather than a parody of its excesses. On the other hand, it might be the album’s composer and lyricist, Tull frontman Ian Anderson, who, in his attempt to tweak a genre he considered too self-important, didn’t recognize that employing elliptical poetic bluster as a send-up of art that thrives on the overblown ultimately is just grabbing another tool from the same kit.

Either way, Thick as a Brick proved an extraordinary success that, ironically, is one of the few prog classics that doesn’t sound like a parody today. Equal parts ambitious and meticulous, it’s a smartly produced collage whose appeals remain undimmed.

It was late 1971, and Jethro Tull was enjoying the success of that year’s Aqualung, which had climbed as high as #7 on the Billboard album chart. As the band’s driving creative force, Anderson was nonetheless perplexed at the reaction to his group’s fourth record, which he believed was mistaken in calling it a “concept album”—to him, any through-line was coincidental, and people in search of greater meaning were reading too much into it.

Listen to “Tales of Your Life,” a track from Thick As a Brick

Progressive rock was in fashion, and to Anderson’s thinking, bands like Yes, Emerson. Lake and Palmer and Genesis were making music whose affectations bordered on pretentious. Anderson determined to answer those who thought Aqualung a concept record by giving them a real one—and, in the process, lampooning the pomposity of bands that were then making hay with outsized conceptual fare.

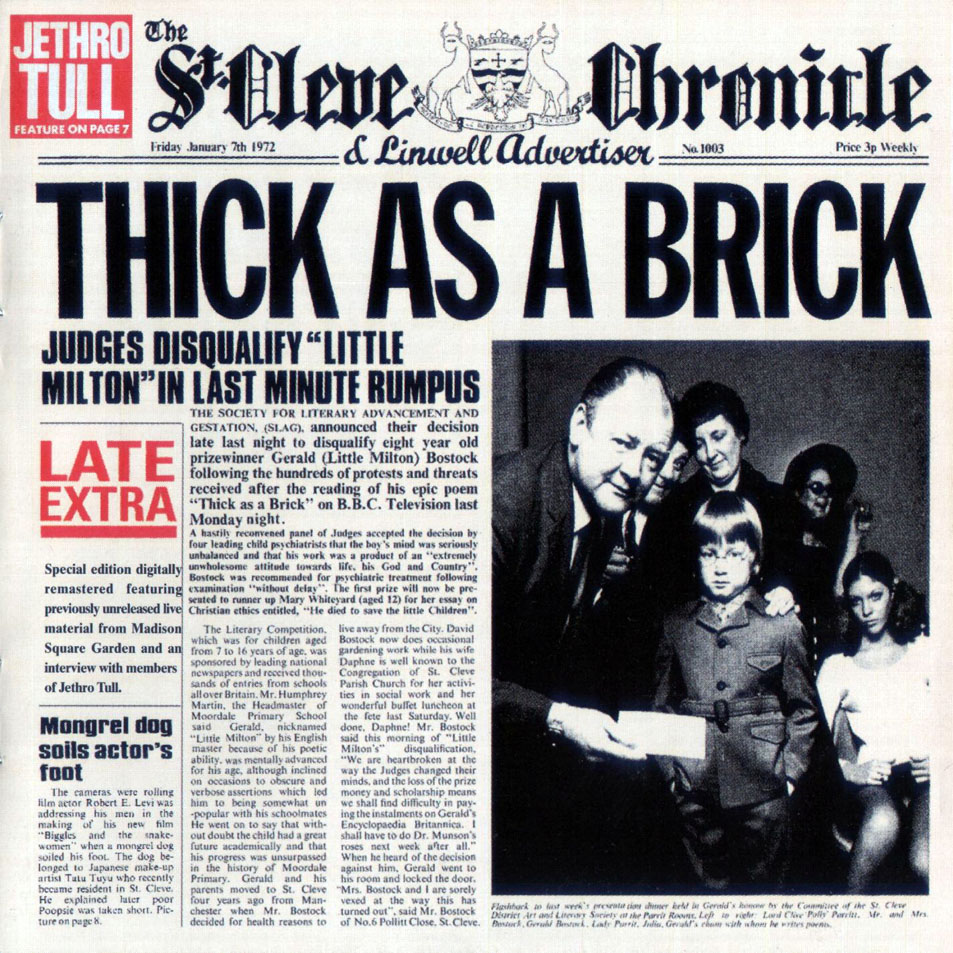

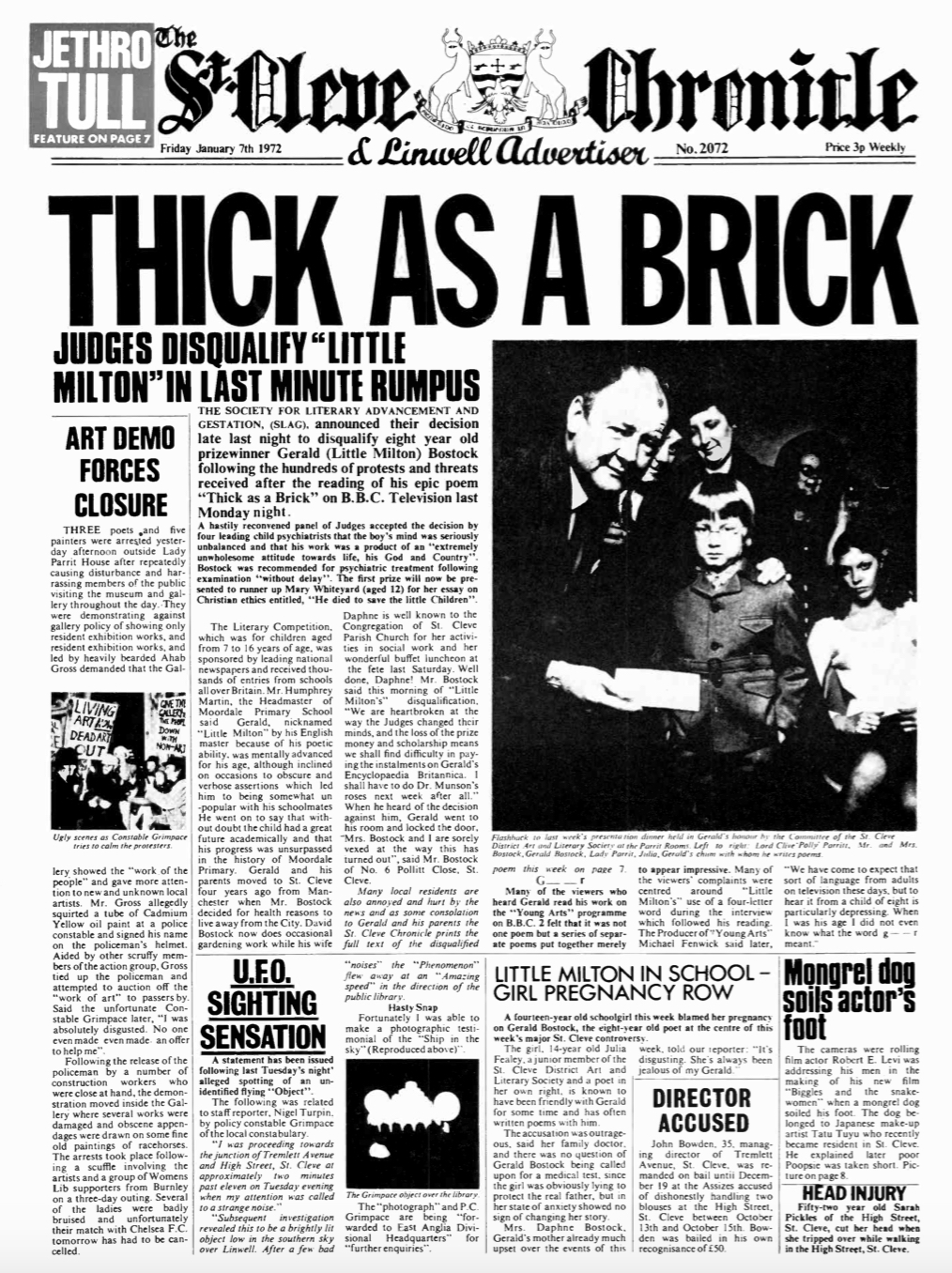

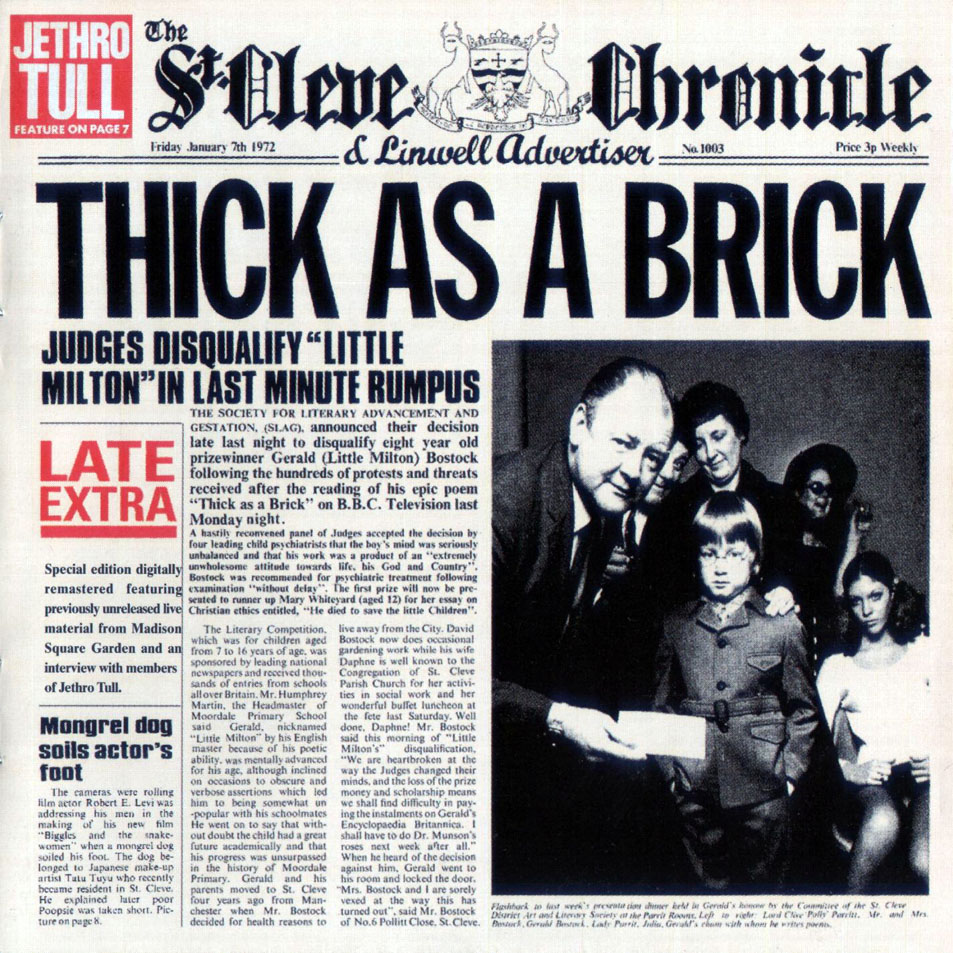

Thick as a Brick is multimedia circa the Stone Age, music married to a newspaper. The album’s sleeve was printed as a custom (and wholly fictional) 16-page paper, the January 7, 1972, edition of The St. Cleve Chronicle & Linwell Advertiser. Anderson drove its articles as personally as he did the vinyl’s contents, writing most with help from Tull keyboard player John Evan and bassist Jeffrey Hammond. Its primary feature is the story of eight-year-old boy Gerald (Little Milton) Bostock, who, after using inappropriate language on BBC Television, is stripped of a poetry award and declared to possess an “extremely unwholesome attitude towards life, his God and Country.” The unsuitable poem, printed on page 7, is the album’s lyrics.

Listen to “You Curl Your Toes in Fun/Childhood Heroes/Stabs Instrumental”

While amusing for its content and relative extravagance, the newspaper is ultimately of minor importance to the record’s overall experience. Designed as individual songs but delivered as a single assembly of suites with connective tissue between, Thick as a Brick was created in two weeks of recording in late 1971, during which Anderson wrote material between sessions, starting with lyrics and then developing accompanying music, and the band learned a new piece each day, stacked upon what it had previously worked out. Although the work found its way in real time, the ultimate product is not loose, perhaps because the process used even more time for overdubs and mixing, where a lot of work clearly was done.

Released March 3, 1972, the album features two tracks by necessity: “Thick as a Brick (Part 1)” on one vinyl side, and “Thick as a Brick (Part 2)” on the other (even with the advent of CDs, the split remained in place—what’s done was done). A 40th anniversary reissue of the record separated the whole into eight pieces composed of 13 total sections, with individual titles that are useful for discussing specific sections.

The record introduces “Really Don’t Mind” with an easygoing acoustic guitar line, to which Anderson applies an equally matter-of-fact vocal. His lightly prancing flute soon affirms the band’s identity, adorning a folk-leaning jaunt alongside an acid lyrical edge. After three reasonably tranquil minutes, rock takes over with “See There a Son is Born.” Frenetic and propulsive, it’s a song in a hurry to get where it’s going, with Evan’s organ and the whining accents of Martin Barre’s guitar as fuel. An audio smorgasbord, it becomes a movable feast when Barre’s hearty electric dressing migrates from right to left in the mix just before the 4:30 mark, one of many tricks and techniques the production employs to keep attention piqued and shifting.

Listen to part one of the title track

Barriemore Barlow’s drums make a similar traipse across the sonic landscape in “The Poet and the Painter,” an interlude that highlights the problem of parodying a thing that embraces bombast. Before electric guitar pieces emerge from both sides of the stereo to propel a bounding romp, Anderson delivers an arch reading of image-rich lyrics, and even if it’s intended as a lampoon, it certainly seems serious enough. If he’s goofing on the worst habits of fellow artists, he also takes advantage of the same tropes, and not only on this record. His aggressive, biting poetry revels in highly personal obscurity and the sort of raw intensity served by his authoritative cadence, sometimes at the expense of what may be intended as bubbling satire: His reading of “Building castles by the sea/He dares the tardy tide/To wash them all aside” takes a back seat to no one when it comes to pure portentousness.

None of which is to say that the album isn’t remarkably listenable. The pleasant lilt of Renaissance Fair-ready pulsation in “What Do You Do When the Old Man’s Gone?” is alluring and cool, with an instrumental flow trimmed by Anderson’s always-pleasant flauting of rock’s conventions. “From the Upper Class” is a different sort of enticement, a haunting turn founded on a jagged-edged jig, where Anderson’s less-than-soothing violin accents enhance sonic tension.

Side one closes with the three-part sequence of “You Curl Your Toes in Fun/Childhood Heroes/Stabs Instrumental,” which runs the record’s gamut of appeals. From dreamy gentleness it shifts heartily, leapfrogging from one instrumental texture to another. Here there’s a xylophone, there a sprinkling of piano, with Anderson’s chipper flute doing substantial lifting as it marches forward. A coordinated throb of organ, drums and Jeffrey Hammond’s bass add punch as the instrumental draws to a close within a playful mix, which starts its fade and then pushes again at the listener’s ear with a fresh burst before evaporating as its last traces mix into the sound of wind.

Side two picks up right there, with gusts giving way to a hollow bell ring before bursting into “See There a Man is Born.” Mixing the formal and the frantic, it is a precise assembly of sounds that breaks into a racing Barlow drum solo before giving way to airy texture. Its stop-and-start journey lands all over the place, yet is cohesive. “Clear White Circles” follows, its flowing acoustic pulse dappled with thicker accents and slight rock trappings alongside Anderson’s deadpan recitation.

Listen to “Thick as a Brick (Pt 2)”

Any argument about the record’s place in the prog firmament is put paid with “Legends and Believe in the Day,” a mellow, contemplative arty hybrid rich with instrumental energy. Behind the likes of “The Dawn Creation of the Kings/Has begun, has begun/Soft Venus, lonely maiden brings/The ageless one, the ageless one,” it’s a tone poem made to sound literate, but ultimately proves most valuable in how it complements the music.

The pulsating “Tales of Your Life” is a carefully constructed swirl, constantly on the move. Traces of harpsichord along the way give it an earthy tone, while a couple of timpani thuds reset attention. The pieces coalesce into a mechanism that never sounds sloppy nor random, leading to a robust crescendo, and lest a listener’s attention drift while surveying its riches, the ring of an alarm clock is there to pull it back.

Wrapping the set with a thematic callback is “Childhood Heroes Reprise”; the pivot to it is abrupt, keeping some of the preceding section’s buildup before turning on a dime. Following one final step on the gas, there’s an acoustic cool-down, with Anderson in full contemplative mode, delivering the album’s final line (and title) with a knowing resignation. The road to that quiet closing is typical of the suite—when it empties into an almost incidental string bed for which there was no precedent on the record, it’s emblematic of an approach for which there is no real limit, where an established sonic palette never stops the production from choosing something new if it’s right for the moment.

Watch a homemade video of “Thick As a Brick Part 2” performed live in 1972

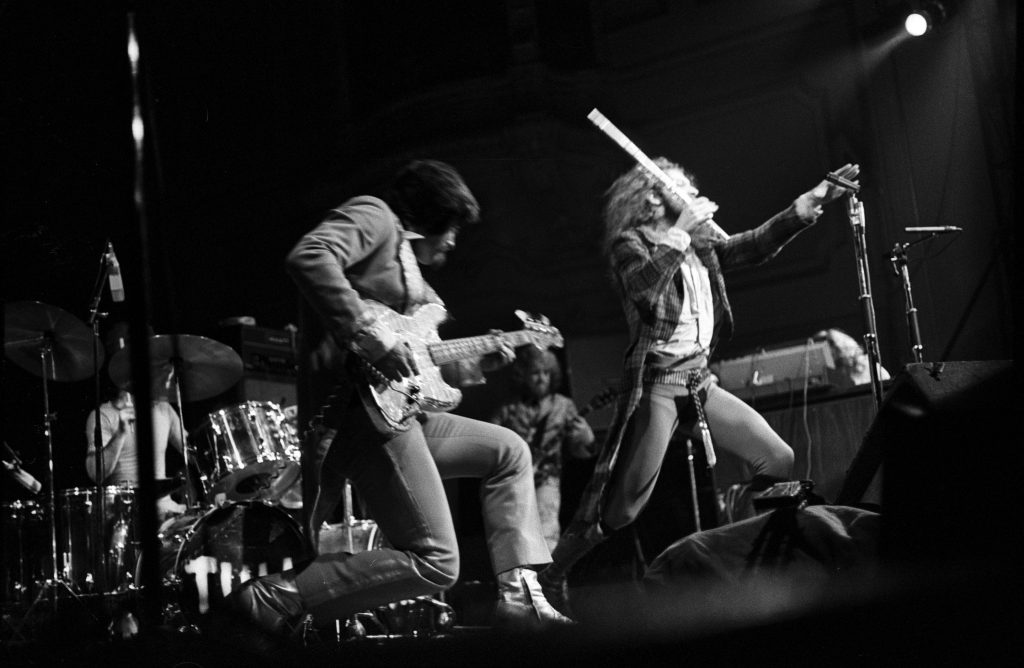

Hardly radio-friendly given its structure, the album nonetheless marked the band’s biggest U.S. success to that point. In June 1972, it spent two weeks atop the Billboard album chart, the highlight of its 46-week run. In the process, it secured Jethro Tull’s standing, transforming an intended jab at the genre into the act’s affirmation as a prog rock staple, an outcome which would be even funnier if everyone could agree on the joke.

Watch Jethro Tull perform “Thick As a Brick” live in London in 1977

[To celebrate its 50th anniversary, Thick As A Brick has been reproduced in its original format, inside a 12-page newspaper. The vinyl edition, released in 2022, is a half-speed master of Steven Wilson’s 2012 remix. In addition, the rare and coveted 40th anniversary CD/DVD special collector’s edition, out of print for nearly ten years, has also been made available. They’re available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Jethro Tull concert tickets are available here and here.

9 Comments

If you know the story about the record label misprints then you know that some early 45’s of “Sunshine Day” were issued under the name of Jethro Toe. If you have this mistaken issued label you’re in for a bit of cash. The original record cost about 99 cents but is worth about $1000. So go running to your 45 collection & see if you have the lucky label….

I preferred Heavy Horses

As a huge fan of Tull’s first four records, I was glad to have Ian’s permission to “sit this one out,” as I did, and, unfortunately, have remained sitting out ever since. I’ve tried, here and there over time, upon reading about this record of that, to re-enter as a fan but have been unable to find a Tull record that has made me want to play it again, as their early ones had. Plus, though the band has gone through various members over the years, replacing Martin Barre against his wishes pretty much put an end to any interest I had in Ian Anderson, under any name he wishes to put his records out under.

Liked the 1st 3 albums much better. I was more of a Mick Abrahams kind of guy. I definitely didn’t get it. I also didn’t much care.

My favorite record from Tull by far. Never liked the followup though.

To go back a few years in Tull time: “It’s an old day tomorrow”. “Brick” and “Passion Play” belong right where they were.

Listened to them once when they came out, and tried again a couple years ago by getting them from my local library.

Two hours I’ll never get back . . .

Do you mean “A New Day Yesterday”? Great song.

When CD box sets first came out, I got the 20 Years of Tull box. “A New Day Yesterday” was from a BBC broadcast. I remember the announcer speaking the intro something like “Don’t you know they’re the biggest thing since the Stones”? “Yesterday” is definitely on of my faves.

After “Thick as a Brick” and the less well received follow-up “A Passion Play,” Jethro Tull returned to “normalcy” (i.e. actual songs). But ever since that time they’ve been considered a “prog” band by progressive rock fans. (Certainly not a heavy metal band as the Grammies thought.) So be it.