James Marshall Hendrix made a lot of music and was filmed and photographed incessantly during a relatively short four-year career span that ended when he died in London on September 18, 1970, at the age of 27. Much has been written about his stature as, many believe, the world’s all-time greatest electric guitar player, but he was far more than just a guitarist as well as singer and songwriter. Jimi Hendrix, born November 27, 1942, was an avatar, a spiritual force in the universe, a philosopher and a cultural icon who personified the youth culture upheaval of the 1960s known as the Age of Aquarius.

James Marshall Hendrix made a lot of music and was filmed and photographed incessantly during a relatively short four-year career span that ended when he died in London on September 18, 1970, at the age of 27. Much has been written about his stature as, many believe, the world’s all-time greatest electric guitar player, but he was far more than just a guitarist as well as singer and songwriter. Jimi Hendrix, born November 27, 1942, was an avatar, a spiritual force in the universe, a philosopher and a cultural icon who personified the youth culture upheaval of the 1960s known as the Age of Aquarius.

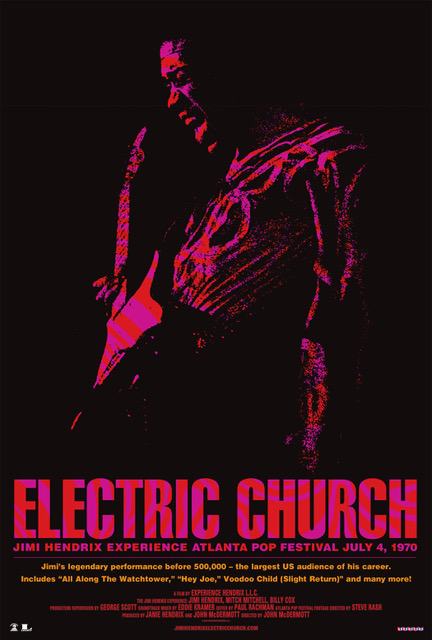

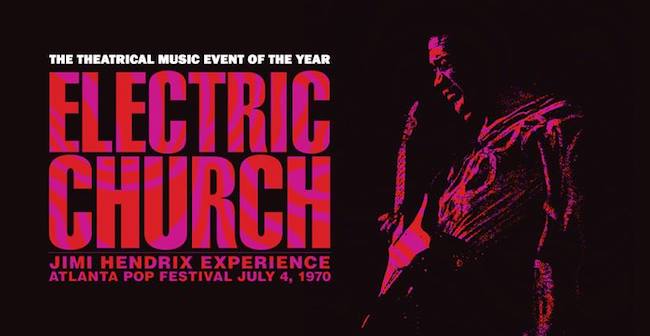

Much of Hendrix’s lore has come to light sometimes years after his death. And due to the compelling nature of the material, it’s always a revelation for music enthusiasts and Hendrix fanatics alike. Rare photos, lost and unearthed performances and minute details of the man’s life were often, say, buried in the files of some photographer’s attic or – as in the case of the 16mm performance footage seen in Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church – stowed away in a filmmaker’s barn.

Original footage director Steve Rash – who later made feature films like The Buddy Holly Story and Can’t Buy Me Love – intended the movie he shot about the 1970 Atlanta International Pop Festival to be a celebration of a down-south answer to Woodstock. He couldn’t line up a deal to finish and release it, and virtually all of the film lay undeveloped inside Rash’s barn for over three decades. Lucky for us, the keepers of the flame at Experience Hendrix LLC came calling in search of the visual record of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Independence Day 1970 appearance to go with the sole surviving multitrack soundboard master they were upgrading for a two-CD audio release, Freedom: Atlanta Pop Festival. The footage survived remarkably intact for being stored under less-than-ideal conditions, and is most definitely a worthy addition to the Hendrix canon.

How does documentary director McDermott do with this resurrected piece of history? He certainly had some great material to work with. Rash’s footage is compelling if not mind-blowing. And McDermott uses its advantages well: Hendrix at the height of his powers headlining a festival in front of an enthusiastic 300,000 or so people – his largest-ever American crowd – that was with him to the max. The disadvantages also serve the film well: The cameras focus on the stage with its psychedelic light show backdrop and Hendrix and Experience members bassist Billy Cox and drummer Mitch Mitchell, sans the usual de rigeur pans of the festival crowd in thrall. Because of a power shortage: the crowd was not lit, except for the thousands of cigarette lighters held aloft in tribute to Jimi.

The scene is set with footage of ultra-conservative Georgia Governor Lester Maddox railing against hippies and the counterculture, naked people dancing around smoking dope and being free, and photo montages of Jimi in various stages of his meteoric rise to fame. A soft-spoken, Gandhi-like Hendrix explains his politics of love, peace and harmony and the concept of the “electric church” to a bemused Dick Cavett as a vehicle for getting “our sound to go inside the soul of the people” in a clip from Cavett’s TV talk show.

The core performance material is fleshed out with talking head interviews with Paul McCartney, Steve Winwood, Rich Robinson, Kirk Hammett, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi, festival organizer Alex Cooley, Rash, publicist Bob Merlis, Mitchell and a very upbeat Cox, and a sweaty, sweetly funny Leslie West (who also played the festival with his band Mountain). They all marvel at Hendrix’ impact on them as musicians: “We all played guitar. We all knew a bit. But he seemed to know more than us” (McCartney). “There was no bullshit about him” (Trucks). “He made his Strat into a lethal weapon” (Hammett). Winwood kvells at the synchronicity of Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner” with the evening’s Independence Day pyrotechnics display: “They’re shooting off fireworks and he’s playing off of it.” Leslie West recalls the day’s conditions: “It was so fucking hot I couldn’t feel my fingers on the guitar” Merlis notes: “Hendrix was the biggest act of the time and in this performance he was at his peak.”

Jimi was a reactive performer. He felt the vibe of the audience and viscerally gave it back to them in how he performed. Watching this footage, that rings true in every frame. In the stage patter and excitement of the performance, in the power of the music. Jimi was on that night, and it shows in the band’s palpable give-and-take with the crowd. Cox sums up his army buddy’s mystique as: “The people were there and the love was there. Jimi made every night a magical moment.” And Hendrix seconds that emotion: “It was great to play for these people.”

A few quibbles: as filmmaker McDermott sums up Jimi’s history, photos appear in a Ken Burns-style montage that are out-of-sync with the periods discussed. And to display the crowd response he lacked, footage shows Jimi musically diddling stageside teenyboppers with his Strat. Viewers might think the sequence is from the Atlanta Pop performance, but it was borrowed but from an earlier one already commemorated on the excellent Jimi Plays Berkeley. It would have been helpful just to have chyroned subtitles on the images so the Hendrix fanatics don’t groan and the audience at large could place the historical visuals in the proper context.

But in the performance department, the actual playing of the music as shot by Rash’s multi-camera crew, and with the audio remastered by Hendrix sonic expert Eddie Kramer, this is a rare pleasure indeed. The audio performance was previously released on a CD box set called Stages, and it sounded pretty good. But the efforts of Kramer makes this show play so much better. The tone of Jimi’s guitar feels warmer and much more like it should, and you can hear the reverb now.

His version of “Red House” is edited down, omitting the two-and-a-half minutes where Hendrix was playing his Strat out of tune (as heard on Stages). “Hear My Train A Comin’” is a churning hunk of burning funk on here, with pungent notes of irony, sincerity and autobiographical je ne sai qua. “Foxy Lady” is so fine you wouldn’t believe he was playing this song for the N-teenth time, taking your breath away with his signature move of playing its solo with his teeth. “Foxy Lady” is a revelation in front of this crowd, who are totally in sync with the master showman up there on the handsomely lit stage.

On “Hey Joe,” Hendrix does his Wes Montgomery rhythm guitar voicing thing in a totally fresh and improvisational context, adding Beatles notes while Billy Cox, resplendent in red white and blue overalls, provides rock-steady counterpoint. “Purple Haze” is likewise is a jazzy workout with splashy altered chords and a revamped rhythm.

The crowning moments of the show are on “All Along the Watchtower,” which gets a full-on Hendrix “sky church” treatment – ascending to the mystical place where the music and the sacred spirit merge – with dizzying key changes, drum-and-bass duels and hearty shout-outs. And, of course, “The Star Spangled Banner,” with its segue into the experimental “Straight Ahead.” Right on cue , the holiday fireworks explode all around the band and are reflected in the light show behind them. It is a cosmic moment, and praise the Lord for the rewind button.

So in this respect, Electric Church shrewdly presents what was there on film, and did the right thing by stepping aside and letting the footage display the magic: you actually get to see Jimi playing his guitar, with no gratuitous cutaways to adoring audience members or distracted stagehands. So in the end I must give this uncovered artifact a hearty thumbs up.

Watch Hendrix talk to Dick Cavett about his “electric church”

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

- 11 Movies That Rock: Woodstock to Spinal Tap - 03/09/2024

- Meet Session Superstar Nicky Hopkins - 02/24/2024

- When the Mood Strikes: 10 Classic Rock Love Songs - 02/14/2024

4 Comments

I believe the bulk of this footage was already oficially released on VHS and Laserdisc in the Eighties, not sure why they say it was sitting in a barn unseen for years. I’m very happy to see it finally get an official DVD release though!

The problem with many music documentaries/biopics, is that you hear all kinds of buzz about it……..and then something happens….never seems to get it to the people that really want to see it.

Citing a few examples……the “An American Band” movie, about the Beach Boys, was supposed to be premiered at the fan convention, but the producers decided to deny showing it, at the last minute.

This basically killed any enthusiasm by fans for the movie.

In the case of the “Wrecking Crew” movie, you constantly heard things about the production…..music fans were anticipating the movie…..but many of the fans that wanted to see it, didn’t know it was out. Then it came and went.

The Hendrix biopic starring Andre 3000 was not handled well, either. Many people that wanted to see it in theaters(again) didn’t get a chance to.

These are but a few examples where music biopics and documentaries get all botched up, in promoting it to the audience that really wants to see such films.

I personally would like this one to do well, but I am not optimistic, given the track record of such films.

Yeah – El Paso, Albuquerque but not Denver??

what about Denver?