It was like that crossroads in a Robert Johnson song for me: The first time I had a chance to compare notes and record collections with the guitarist who then went by Jimmy Hendrix – the Jimi came later – was after a gig at the Gaslight Cafe in Greenwich Village that he played with John Hammond Jr. at the end of the summer of 1966. I didn’t know it then, but there on the steps leading down to that cave of a club was my first brush with a genius whose music became a central part of my life. Today, decades after his passing on September 18, 1970, Jimi Hendrix continues to mesmerize millions worldwide.

It was like that crossroads in a Robert Johnson song for me: The first time I had a chance to compare notes and record collections with the guitarist who then went by Jimmy Hendrix – the Jimi came later – was after a gig at the Gaslight Cafe in Greenwich Village that he played with John Hammond Jr. at the end of the summer of 1966. I didn’t know it then, but there on the steps leading down to that cave of a club was my first brush with a genius whose music became a central part of my life. Today, decades after his passing on September 18, 1970, Jimi Hendrix continues to mesmerize millions worldwide.

It was a heady if not utterly magical time in music as well as an underground culture that would soon erupt into the mainstream. And nowhere was that more evident than in the Manhattan bohemian enclave of Greenwich Village. It was already known as the nexus of a folk music revival that was yielding not only stars but soon-to-be legends like Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul & Mary and Simon & Garfunkel.

The popular myth is largely that Hendrix became the groundbreaking artist we now know after he decamped for England later that year. However, I can attest from having been there and known Jimi during his brief but critical time in the Village that it’s where he evolved into the artist and personality that would become a musical and cultural icon.

Mystical Artist in a Magical Place

I’d been frequenting Greenwich Village since 1963 when I attended high school on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, spending time in a far more educational milieu, given my interest in blues music.

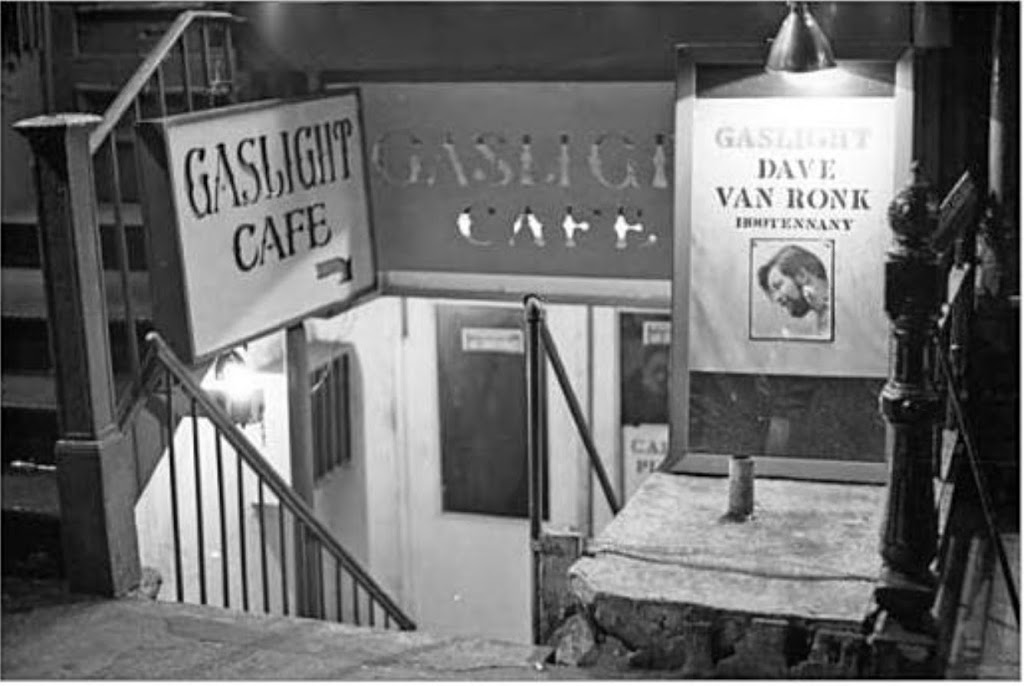

By 1965 I was worshipping every Tuesday night at the Gaslight, where Dave Van Ronk held court in a weekly residency. Known as “The Mayor of Macdougal Street” for his dominion over the epicenter of the Village music scene, Van Ronk had a wealth musical knowledge that went far beyond the sometimes narrow “folk” confines of that scene into a breadth of American styles.

The dark and intimate basement club was where I first saw Hendrix, sitting in with Hammond.

It was across the street from his customary perch at the Café Wha? – a “basket house” where Jimi played for spare change, riffing on all the Otis Rush and Albert King songs he’d studied off records – the same records that I had in my collection. The set by Hammond and “Jimmy James” – the moniker he adopted for his first group the Blue Flames with Randy Wolfe, aka Randy California, later of Spirit – was a nasty, amped-up performance of rural country-blues and deep Chicago blues songs from the repertoire of Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf. Most of them came off of Hammond’s seminal 1965 So Many Roads album, which Hendrix knew intimately, having studied it intensely. On it Hammond was backed by Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm and Garth Hudson – later to become The Band – along with Mike Bloomfield on piano (not guitar) and “Memphis Charlie” Musselwhite on harp.

It was across the street from his customary perch at the Café Wha? – a “basket house” where Jimi played for spare change, riffing on all the Otis Rush and Albert King songs he’d studied off records – the same records that I had in my collection. The set by Hammond and “Jimmy James” – the moniker he adopted for his first group the Blue Flames with Randy Wolfe, aka Randy California, later of Spirit – was a nasty, amped-up performance of rural country-blues and deep Chicago blues songs from the repertoire of Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and Howlin’ Wolf. Most of them came off of Hammond’s seminal 1965 So Many Roads album, which Hendrix knew intimately, having studied it intensely. On it Hammond was backed by Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm and Garth Hudson – later to become The Band – along with Mike Bloomfield on piano (not guitar) and “Memphis Charlie” Musselwhite on harp.

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

It was truly a privilege to be among the 30 or so people that night who were digging these two urban bluesmen playing the shit out of these songs on electric guitars. They worked out on a version of Muddy’s “Long Distance Call” that was so rockin’ yet fun at the same time. Hammond provided the rock-steady rhythm and the authentic vocals, and Jimi just wailed and wailed on his Stratocaster. What I remember most about that one was Jimi’s characteristic guitar talking technique.

They rocked the tiny house and got up a major sweat on the Johnny Shines version of “Ramblin Blues,” with no drum kit but a steady toe-tap from John providing the beat and Jimi, again, wailing on those distinctive 12-bar lead lines that punctuate the song. And they both got excited when they lit into Jimmy Reed’s “Big Boss Man,” with its “Can’t you hear me when I call” refrain. They were killin’ it that night.

They rocked the tiny house and got up a major sweat on the Johnny Shines version of “Ramblin Blues,” with no drum kit but a steady toe-tap from John providing the beat and Jimi, again, wailing on those distinctive 12-bar lead lines that punctuate the song. And they both got excited when they lit into Jimmy Reed’s “Big Boss Man,” with its “Can’t you hear me when I call” refrain. They were killin’ it that night.

After they set their guitars down for a break, I got up the gumption to have a conversation with Hendrix about the records we had in common. As gritty and fierce as he appeared on stage, the man I sat with that night was a study in contrasts. He had a mystical, soft-spoken air about him, and an intense gaze that kind of misted over when he was apparently reliving the epiphanies he’d gained from these pieces of vinyl. We were like two kids from opposite sides of the universe hovering over a stack of comic books.

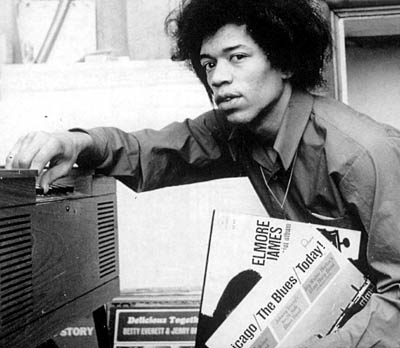

Jimi, born November 27, 1942, was into some of the same guys from the three-record Chicago/The Blues… set that I was, notably Johnny Shines, Otis Rush and J.B. Hutto & His Hawks. I was a budding blues harmonica player from the Bronx who used these same records to learn my licks and fills, and was partial to The Junior Wells Chicago Blues Band, featuring Buddy Guy on guitar, which was on Volume 1. Wells’ rendition of “Help Me (A Tribute to Sonny Boy Williamson)” was a constant on my record player, and Sonny Boy II was my master in much the same way as Muddy, Albert King, Elmore James and The Wolf were Jimi’s.

We also talked about our mutual love for John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Muddy’s The Real Folk Blues and More Real Folk Blues. He told me he loved the “real” folk blues of the title and inspired me to play from the heart so that I became my instrument.

“Sure, man, you know,” he said in that syrupy, not-quite stoned but beautiful voice, “‘Killin’ Floor’ is a revelation. It’s not about a slaughterhouse at all, you know. It really is about one of [Howlin’] Wolf’s wives who shot him full of buckshot. She had him down on the Killin’ Floor and he should have quit her a long time ago.”

Another bit of etymology he divulged was the origin of the term “freak.” It’s West Coast slang for doing the nasty in the back seat of a car. He later adapted the term to denote his hippyish appearance, as in “letting my freak flag fly.”

Stone Freedom

The evolution of his flamboyant style was happening then, and it flowered in the Village. Photos of Jimi as a sideman with these groups show him wearing the mohair suit and skinny-tie uniform, but Little Richard was his crucible. He dared to show up onstage with a fancy frilly shirt and got fined for it. “I am Little Richard. I am the King of Rock ‘n’ Rhythm and I’m the only one who’s going to look pretty on stage… you will please turn in those shirts or else you will have to suffer the consequences.”

Then there was another meeting about Jimi’s hairstyle. Jimi wasn’t going to let anybody cut his hair, so after five months with Richard, he was gone. When he landed in Harlem, his unique style was already developed, and his hair was really long. He suffered mightily from the taunts of the locals – “Oooh what is this, Black Jesus?” “Is the circus in town?”– to the extent that he had to flee, stung by the disrespect from his own people. He fled to the Village where he felt at home, soaking up everything like a sponge and hanging with the groovy people.

The Village was where his luck changed. John Hammond booked himself and Jimmy James and the Blue Flames into a two-week stint at the Cafe au Go Go in September of ’66. That was the next time I got to experience Hendrix in all his showman’s glory. I haunted that place, and on more than one night I got to witness the once and future king playing all his tricks coming from the heart, as he had told me to do. Hammond, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames were augmented by a revolving roster of keyboard players like Barry Goldberg and Al Kooper.

Listen to Jimmy James and the Blue Flames perform “I’m a Man” in 1966

The place had a low ceiling, and sometimes it seemed the neck of Hendrix’s Stratocaster was aimed like a rocket poised to go through the roof. I remember thinking – and telling my pals later – that he was some kind of amped-up incarnation of Muddy Waters in a slim, six-foot frame, somehow making all this beautiful noise and playing it straight from the heart. He was at that moment what he was on every stage until the day that he died: a genuine musician who was one with his instrument to the point that it spoke through him and all his ideas and spirit were laid bare for anyone to see.

The Cafe au Go Go gig proved to be historic – that was where members of the Beatles, Stones and Animals as well as Bob Dylan came down to check him out. And his all-too-brief life entered its next historical chapter, the one during which everyone else got to know the name Jimi Hendrix.

[Hendrix performed in New York City many times in 1967, including another run at the Cafe au Go Go from July 21-23.]

Adapted from the first chapter of Hendrix Now! Backstory of a Legend, a Jimi Hendrix Foundation project by Noe Gold, to come from a major publisher. Quotes from Starting At Zero © 2013, Gravity Limited, used by permission.

- 11 Movies That Rock: Woodstock to Spinal Tap - 03/09/2024

- Meet Session Superstar Nicky Hopkins - 02/24/2024

- When the Mood Strikes: 10 Classic Rock Love Songs - 02/14/2024

14 Comments

The process of writing this has brought me back to those more innocent times. Thanks for reading it.

On this day September 18, 45 years ago, James Marshall Hendrix left the planet for a more tranquil universe. While November 27 is a day I often celebrate, September 18 is for me to contemplate.

I know it could be interpreted as a plug but the writing of this article, an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Hendrix Now! Backstory of a Legend, was for me a spiritual experience. The insights gained from the process of going back in time to more innocent and vibrant times back in Greenwich Village – where I came of age in the same place as Jimi did – are still resonating all ’round my brain as I reach for my copy of the Red House: Variations on a Theme cd which I will listen to today. There are seven variations on this theme, one of them by John Lee Hooker.

Good theme music for today’s meditation.

– Noë the G

Founding Editor, Guitar World

Creative Consultant Jimi Hendrix Foundation

Please go to http://www.hendrixnow.com

@Hendrix_Now @DoctorNoe222

to express your feelings and support.

#JimiHendrixRestInPeace

Ten things about Jimi every one should know.

1. He served his country.

2. He played bass and other instruments as well as guitar.

3. He didn’t know how to read music.

4. It is said that he had perfect pitch.

5. He once sat in on guitar for Engelbert Humperdinck but didn’t want it to hurt his image so Jimi played behind a curtain.

6. When his family got the call in Seattle that he had passed away a rocking chair in the corner started to rock, and Jimi’s dog started to howl. His Grandmother said it was Jimi’s spirit.

7. He didn’t think he was the best, and he said compliments distracted him.

8. If he would have lived he had planed to attend Juilliard, an awesome music school. He also was supposed to record with an orchestra.

9. He hated Seattle and didn’t want to be buried there.

10. He saw Elvis Presley when he was fourteen and it changed his life.

–Thank you, Gary Slavin for this list

http://www.hendrixnow.com

How do you know that Gary quotes are valid? I’d be careful using another mans quotes in a forum such as this one

5. To the best of my knowledge, it was Noel Redding, bass player with the original Experience, who played guitar with Engelbert Humperdinck hidden behind a curtain.

Noel had been around the British music scene for a couple of years before he got the gig as Jimi’s bass player, and was primarily a guitarist. He sat in for Engelbert to earn a few extra pounds during a joint tour (Engelbert was the headline act, Jimi was support!).

This was the very early days of the Experience, and they were all pretty broke, so when Engelberts guitarist was unwell, Noel sat in, but hid behind a curtain so as not to spoil his image, or Engelberts. Noel’s afro perm and pink flares didn’t really blend with the rest of the band.

Pingback: Hendrix Becomes Jimi in The Village | Gotmymojoworkin.com

Thanks, interesting read. I was lucky enough to spend a week with Hendrix bassist Billy Cox ,soon after Jimi passed. Billy produced an album for me in Memphis. Poobah

A terrific article and a very unique article, citing as it does, solid, eye witness sources.

Quick note: though it wasn’t stated explicitly, Jimmy Page never saw Hendrix live.

Thanks for the great piece of work, Noe.

This made my day and truly informed me.

a truly great article …… note: that photo w/ the records is from ’66

also: there are no known recordings of Jimmy James & The Blue Flames

Ah but there is one in my brain.

– Noe the G

I was lucky enough to see Jimi in Central Park in July of 67. He opened for The Rascals I had seen a few times on Long Island. Jimi was not on the bill or ticket so you can imagine my surprise when The Experience came out & started playing. I was blown away. Who is this wild man? What’s his name? Where did he come from? All ran through my head. I left after Jimi’s set & the next day I went to a record store on Main St. in Flushing & asked the owner if he knew a 3 piece band wit a black guitarist with wild hair & 2 white guys playing along with him. I mentioned a song about “scuse me while I kiss this guy”…lol. He brought me right over to the “Are You Experienced” album which I bought for $2.98. I played the shit out of it, even to a point where my parents enjoyed some of the songs after 10 months of listening to it. From that day forward, I went to every show Jimi played in the NY area. All the shows at the Fillmore, New Years Eve w/Band of Gypsies. Hunter College & even his last American show at Randall’s Island. Jimi changed my life & taught me that you can make music in any different ways. I miss him, his kindness, his humility & his writing & playing. Every once in a while, God creates special people like Einstein, Disney & Hendrix who teach us to never stop imagining, creating & pushing the envelope as far as possible…Happy Birthday Jimi. I look forward to meeting you on the next level….Dolph

I don’t know if there’s much left to be said about Jimi, except to say that with all the accolades about him pioneering the sounds and styles of the electric guitar, his underrated vocals, and his unique songs, his greatest talent, that, in my opinion, is the most underrated was his ability to hear these songs sonically realized in his head and to actually be able to create them orchestrally with multi tracks of various instruments, and using the guitar to create parts and sounds, like no one before him, that wove together in amazing tapestries of songs throughout his four remarkable and individually unique studio LPs. I count “Cry of Love” amongst those Jimi created studio recordings because he had all but done the final mixes of what was to be his next studio release, when he left us. It’s a wonderful record, and shows the next step in Jimi’s songwriting direction. To me, it’s every bit as good as his previous releases, in its own stylistic way.

It’s unfortunate and downright tragic that his baby sister legally took over his legacy in what was initially though to be an act of preservation, with Experience Hendrix, but turned out to be the most insidious form of piracy and greed that only a family member who had no real affection or love of the music could manage. Had Jimi known he was going to leave this Earth when he did, he would have burned those half-baked jam recordings that his sister has released postumously as “Hendrix” records. Sadly, there are actually young people out there who think that these records are what Jimi Hendrix was, and have no knowledge of “Electric Ladyland,” or any of his actual masterpieces.

very well written saw him with the Monkees

Heyyyy take that back about Seattle!!! He’s a favorite son here and this was home. He was ours first!