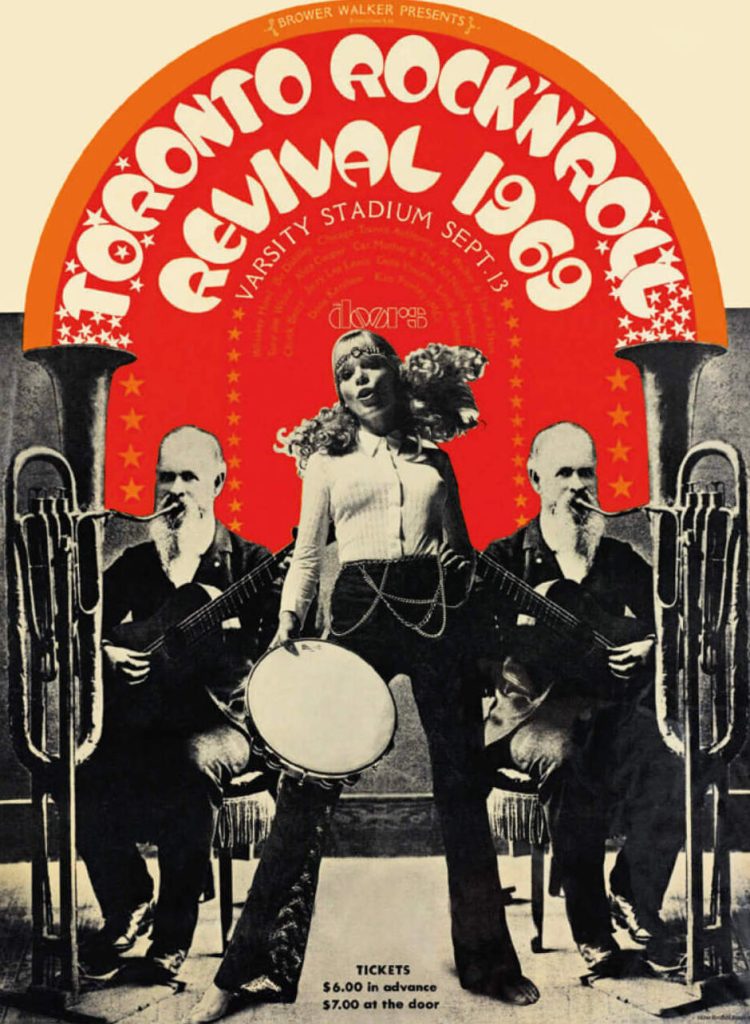

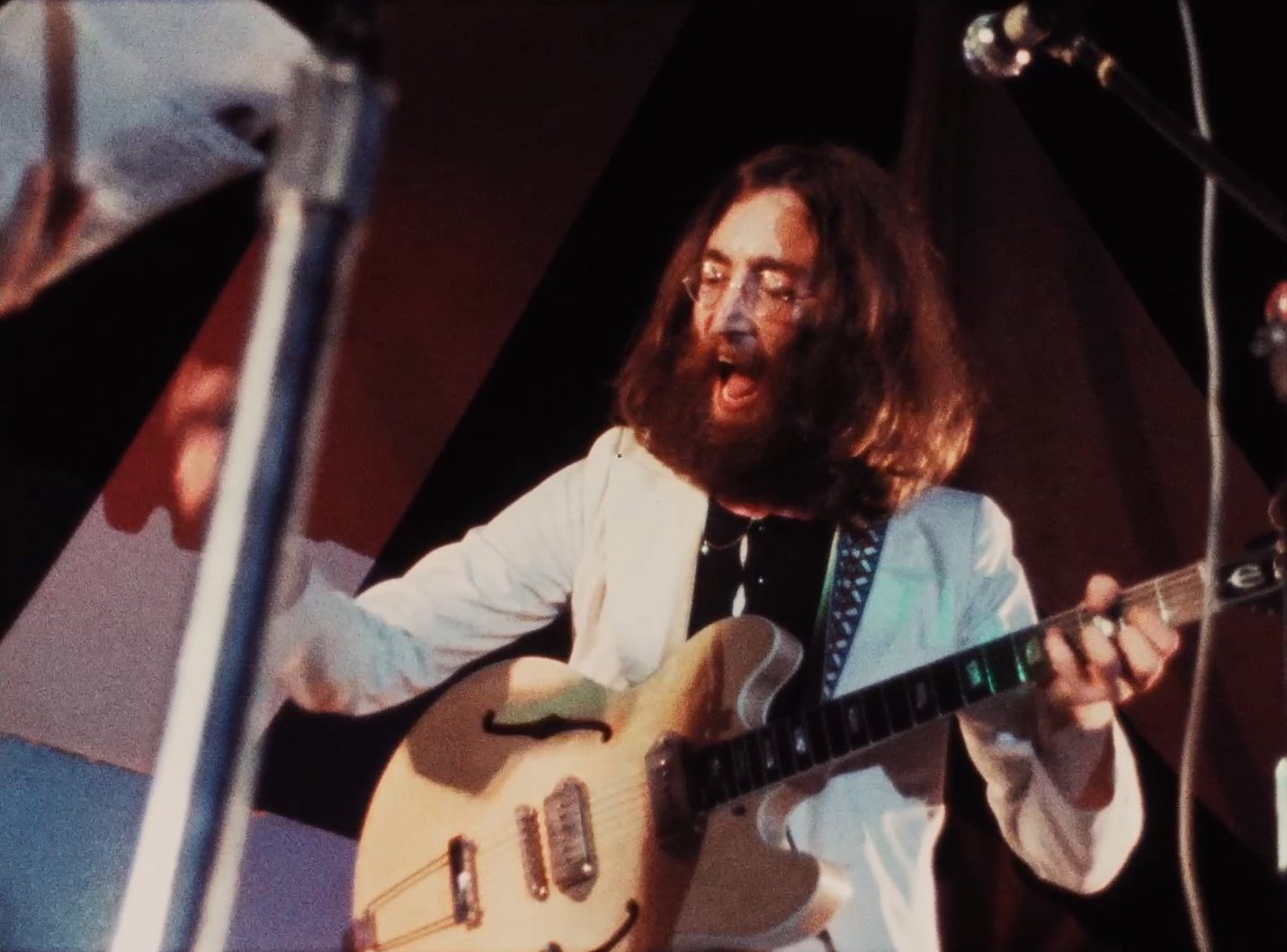

A new documentary Revival69: The Concert That Rocked the World, takes a fresh look at the Sept. 13, 1969, rock festival held at Varsity Stadium in Toronto, Canada, which featured the debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band. The concert, called the Toronto Rock ’n’ Roll Revival, also featured some of Lennon’s early heroes—Jerry Lee Lewis, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent and Little Richard—as well as the Doors and newcomers Chicago Transit Authority and Alice Cooper and others. (The Plastic Ono Band segment was released on an album, Live Peace in Toronto 1969, late that year.)

A new documentary Revival69: The Concert That Rocked the World, takes a fresh look at the Sept. 13, 1969, rock festival held at Varsity Stadium in Toronto, Canada, which featured the debut of the John Lennon and Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band. The concert, called the Toronto Rock ’n’ Roll Revival, also featured some of Lennon’s early heroes—Jerry Lee Lewis, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent and Little Richard—as well as the Doors and newcomers Chicago Transit Authority and Alice Cooper and others. (The Plastic Ono Band segment was released on an album, Live Peace in Toronto 1969, late that year.)

For the new documentary, director Ron Chapman interviewed such key cultural figures as bassist/artist Klaus Voormann, artist manager Shep Gordon, Cooper, the Doors’ Robby Krieger, Chicago’s Danny Serafine, promoter John Brower, SiriusXM DJ Rodney Bingenheimer and Geddy Lee of Rush. Debut U.S. screenings took place in March 2023 at SXSW in Austin, Tex. The film has been acquired by Shout! Studios for North American distribution rights.

Between 2000-2018, music journalist Harvey Kubernik, who served as a consultant on the documentary, interviewed the late Kim Fowley, Brower, Densmore and the late Oscar-winning filmmaker and documentarian, D.A. Pennebaker—who filmed the original festival—about this landmark event. Pennebaker/Hegedus Films is the executive producer. Here are highlights from those interviews.

John Brower

How did this monumental endeavor originate?

I called Lennon at Apple Records asking if he wanted to emcee the gig. Lennon said no but he would like to play.

Jim Morrison and Lennon met at the show but there is no visual documentation of that. What was their meeting like?

When Morrison and the Doors heard that Lennon was now going to play, he asked [Doors manager] Bill Siddons to set up a meeting to discuss who would headline the show. There was a knock on the locker room door and it was Bill [Siddons] and Morrison asking if they could talk to John and me. I grabbed John and we met in the hallway. The two singers didn’t acknowledge each other or shake hands but Siddons wanted to ask Lennon if the Doors could go on before Lennon. John’s eyes opened wide and he said, “No, you guys are the headliners. That means you go on last, that’s the way it works.” John was not about to be upstaged by Morrison and whatever antics he might pull off. Just then, Little Richard appeared, and said to us, “Hey, I will headline! I will headline!” I then told Morrison, “Look, I have already paid you guys, so if you don’t want to play, you can go back to your hotel room and relax. No problem.” Morrison nodded at Siddons and they agreed to go on after Lennon. Then Morrison said, “One thing: We want to be on the side of the stage so we can watch the set.”

Kim Fowley

How did you get the gig as master of ceremonies of the concert?

I knew some of the promoters involved. John Brower was a visionary and I dealt primarily with him and [music journalist] Ritchie Yorke. I got the Toronto job because I was the voice of the love-ins in L.A. in 1966, ’67, ’68 and ’69. I did some pop festival shows with the Doors, the Seeds, Jimi Hendrix and Jefferson Airplane. I knew what to do with a large audience like 100,000 people. My job was not only to announce the date but also be a consultant and tell them how things were going.

We had a problem: We only sold 2,000 tickets before and no one was interested in coming to Canada from America via Detroit and the other cities. At the time, halfway through the week, I met with the promoters, John Brower and Ken Walker, and Thor Eaton of Eaton’s Department Store, who financed the thing. It was my idea to bring John Lennon over; John Brower executed the transaction. I was suggesting the people to be there. They threw in Cat Mother and the All Night News Boys and somebody else came up with Lord Sutch, Chicago Transit Authority and Alice Cooper, who also backed Gene Vincent.

How did you come up with the idea of bringing in John and Yoko?

I told them to get John Lennon to show up. I said, “John Lennon is the most competitive [member] in the most competitive group. So, call him up on a ploy level and invite him and Yoko on a chartered plane, which Mr. Eaton can provide, so they can sit at the show in a royal box kind of thing.” John Brower called Apple Records. John Lennon got on the phone and heard the pitch. Ritchie Yorke was in the room with them and he further explained who I was and about the promoters and the event. It was at a time when the Beatles would be at the Apple office.

Originally, John was asked by Ritchie if he wanted to come for free and sit there and enjoy seeing his heroes. And he replied that he wasn’t a member of royalty and would rather join in and be a part of it and didn’t require any money. He said, “Is it OK to play? I want to try out this thing I’m putting together with Eric Clapton, Yoko Ono, Alan White and Klaus Voormann.”

But Lennon did require film rights and recording rights. He was in the music business. He was in show business. [Lennon’s representative] Allen Klein showed up and D.A. Pennebaker showed up with the film unit and this whole thing was recorded and a gold album came out of it.

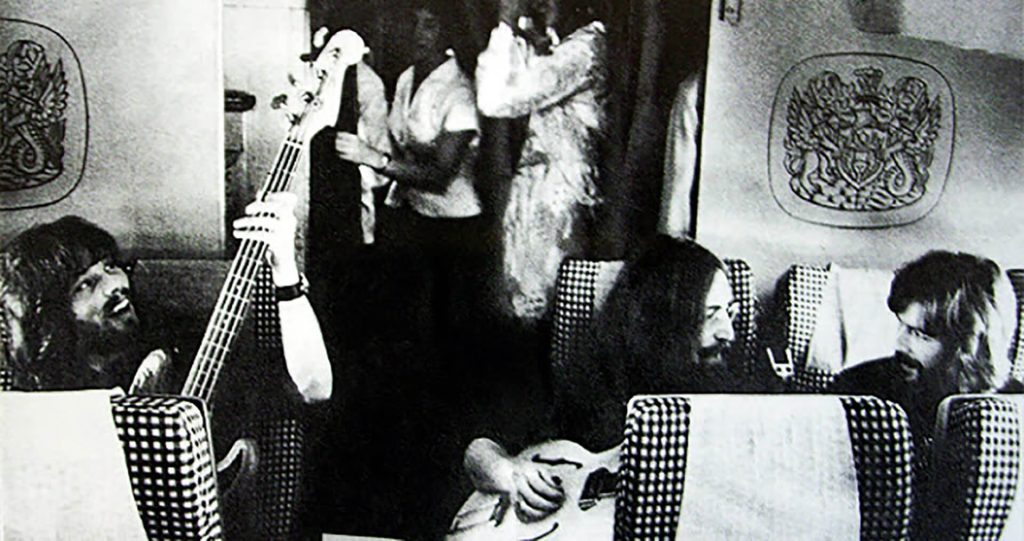

The band rehearsed on the plane over from England, correct?

They [the promoters] sent the plane and John and the band jammed and rehearsed on the way across the Atlantic. Yoko got sick on the way in. In the morning, all the Apple people from New York under Allen Klein’s supervision were already bringing in the recording equipment. I don’t think this was anyone exploiting John Lennon. I think John Lennon was a bright guy who called his then-manager, Allen Klein, and told him to “do the paper” with these promoters and “let’s make a live album.”

[After Lennon was announced] people started driving across the border and all over the world. Then DJs got on the radio, and everyone wanted to see what John Lennon would do outside of the Beatles.

Any incidents or problematic performers at the venue?

Any incidents or problematic performers at the venue?

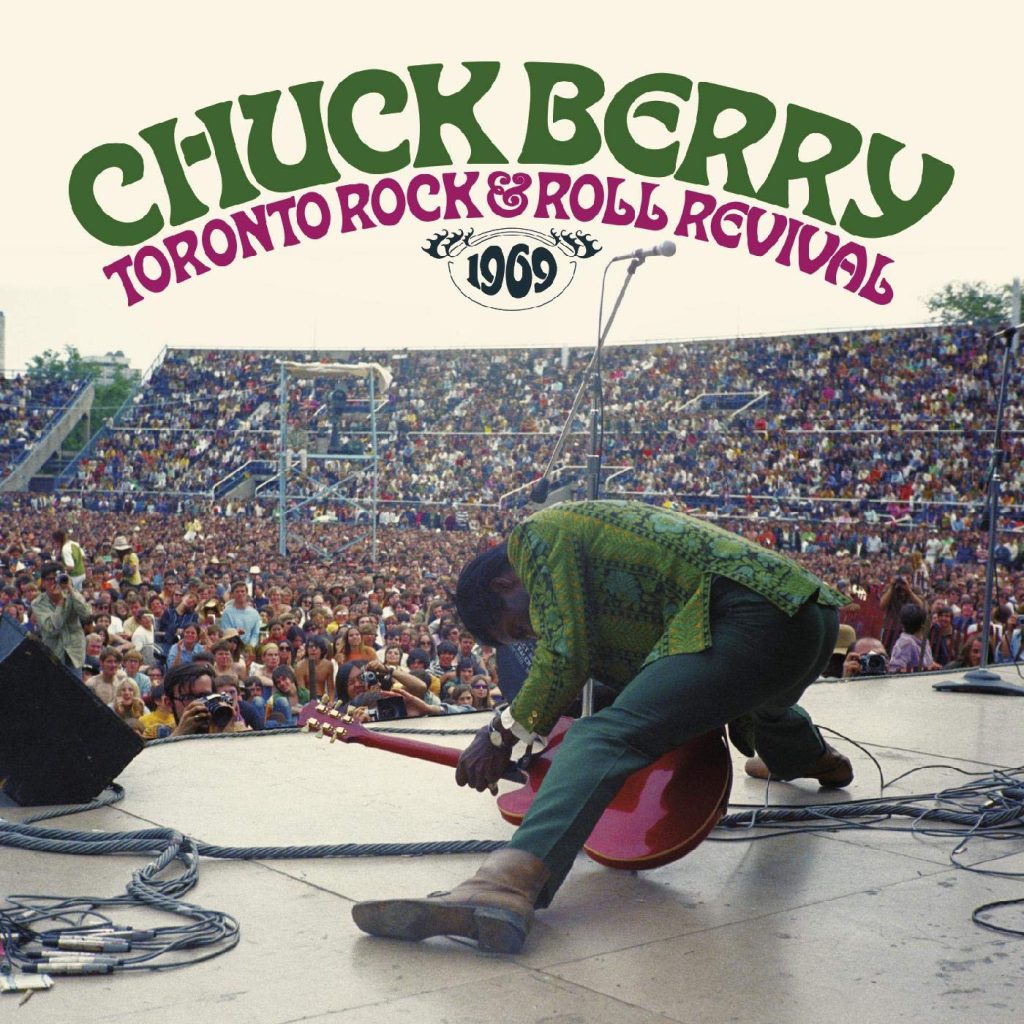

One thing that happened was Chick Berry, Bo Diddley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard all came up to me at the same time backstage and said, “We think all four of us are the Kings of Rock ’n’ Roll. How you going to solve that problem in the introduction?” They had concerns about billing since each one wanted to be the King of Rock ’n’ Roll that night. So I had to amend each mention. The visual of all four of them in front of me: egomaniacs whose time had passed demanding to be Kings of Rock ’n’ Roll.

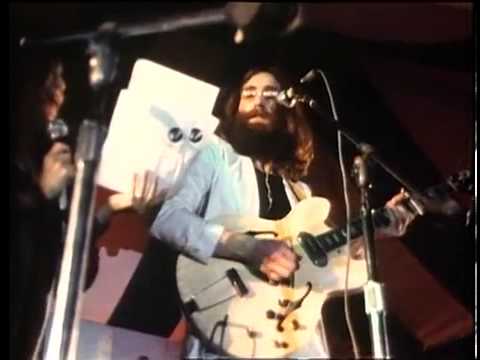

What was the scene like before John and the group came on stage?

Lennon was nervous. “Are you all right?” “Yes.” The big moment comes and the lights are blinding. Everything is on and John Lennon summons me to the apron of the stage on the side by the canopy. I was dressed in a purple suit. He was in a white suit. Then John threw up, and he started to cry. He said, “I’m terrified. Imagine if you were in the Beatles as the only band you’ve been in in your life. The first time you are to step on stage with people that weren’t in the Beatles. You’re about to go on stage with your wife, a friend, another friend, and a complete stranger, with songs you had learned acoustically on an airplane on the way over from England with jet lag. You would be terrified. Do something so the kids don’t know how scared I am.” He was that vulnerable.

That’s all he knew. “Do something! Please so something so people won’t know how afraid I am to go out there.” He went ahead of his band. They were behind him. He was in a bad way.

How did they come up with their setlist?

They just went on and played. They didn’t sit there and kibbitz or talk to anybody. The repertoire performed fit the theme of the event, which was a rock ’n’ roll revival booking. It was appropriate to open with “Blue Suede Shoes” and play “Money” and “Dizzy Miss Lizzy.” That night Plastic Ono Band did simple rock ’n’ roll songs where sloppiness is a charm. It’s nighttime outside and people are drunk and stoned. Klaus Voormann on bass was fine. He had been in Manfred Mann before. Alan White was a member of Yes at the time, or a bit later. Eric Clapton had just been in Blind Faith.

Related: Another “lost” rock festival preceded Woodstock by two weeks

How did you bring the Doors to the stage?

After Plastic Ono Band departed, I said, “Get ready for the Doors, who are coming on next!” Then there was an hour wait. The Doors started doing their thing. Around the third song of the set, out comes Chuck Berry. He approached Jim Morrison on stage and Jim Morrison stopped the show and said, “Chuck, you never let kids jam with you. You can’t jam with us. Be nicer to kids and maybe someday we’ll let you jam with us.” And he was ordered off the stage by Jim Morrison.

The Doors were excellent that night. They had to be with all that going on. They closed the show and had to follow John Lennon, the Plastic Ono Band with Eric Clapton. That was hard.

I remember a while afterwards, [Doors keyboardist] Ray Manzarek felt Lennon’s appearance was some sort of psychic release from the pressures of being a Beatle. In a non-paparazzi time of 1969, no one had the brains to photograph John Lennon and Jim Morrison together. Nobody has the picture, because no one thought of taking one because there wasn’t a paparazzi culture there to document it. They did speak because they had to.

Related: 1969 in rock music

The day after the concert you met with John and Yoko. What did you talk about?

Eric Clapton escorted me to the sitting room of this mansion and a very quiet John Lennon, who was dressed very casually and was sitting on the floor in a Gandhi position, looking at Yoko, who was sitting in a chair. Klaus was next to them. John said, “Thanks for introducing us.” We shook hands. He was very gracious to me. John was enjoying the fact that he could go on stage and do something without the restriction of being a Beatle. He hadn’t played music outside the Beatles. That’s when the Beatles stopped being the Beatles. I told him to have a nice trip back. Goodbye. Never saw him again.

Watch John and Yoko debut “Cold Turkey” live in Toronto

John Densmore

Tell us about the Toronto concert.

We [the Doors] came to Canada and at the airport we all got into two black Cadillacs. Then, all of a sudden, several hundred bikers started zooming along beside us; they were in a club called the Vagabonds. A hundred Hells Angels types, and we’re going, “Hey, this is kind of cool.” We came into the stadium, a football stadium, and they drove the limos all the way around the entire circle of the track with these 150-200 bikers leading us. So it’s real profound. Like, “Oh my God. Here comes Lucifer.” It was really great.

I went backstage and Eric Clapton said to me, “Isn’t this a crazy life?” Eric had not cleaned up his act yet. I didn’t get to see John. We had to follow John and Yoko, and it’s a monster band: Eric, Klaus, Alan. Ridiculous. They start and then we hear this noise coming out of the speakers. Everyone on the stage is saying, “What the fuck is going on here? Some feedback with their set?” And then everyone notices a bag on the floor of the stage with a wire leading from it. Yoko is in the bag with a microphone, warbling. It was great. We didn’t know what the fuck was going on. “Oh, wait a minute, she’s in there.” Really outrageous. I mean, you know, John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band walked out on stage and it was the biggest roar of the century and we’re supposed to follow this group? We played the best we could. In my opinion we were fine. We weren’t great. We weren’t lousy. We were fine. But everyone was so in awe of the Mop Top…It was great.”

D.A. Pennebaker

You documented the Toronto moment but didn’t film the Doors. Why not?

Morrison had come to me a couple of times and he obviously was interested. He and [rock scenemaker] Bob Neuwirth came and showed me Jim’s student film, HWY. I was not impressed, but that didn’t mean anything. I was interested in anybody who was a poet and wanted to make films. That was interesting to me. I didn’t look down like this was amateur. But the fact is that he was a boozer, and that’s a hard thing to make a film about. My father was a boozer. You can’t count on getting their real lives. You get something else. They put on a kind of a show. And that was a problem. When the Doors got to Toronto, they were all very puffy. They looked like chefs in a big restaurant. I would have shot them, but we couldn’t afford to stay for the two days. We paid for the track for Yoko and John and gave it to them to release as a record. It’s an amazing thing.

It was the end of the Beatles. They understood it and at the end they fell silent. John looked out and it was kind of scary and nobody was there. It was a funny moment. And they all left the stage and I remember a piece of paper blowing across the stage and slowly the audience came to life. I thought, “My God. This is a fantastic wake.” Yoko was so crazy, but still, there was something so fascinating about what she did. You could see she did it with absolute conviction. What she was bringing to me was a kind of funeral cry for something that was lost. At the time I wasn’t sure how I felt about it. But I did welcome it.

Watch the official trailer for REVIVAL69: The Concert That Rocked the World

Author and music journalist Harvey Kubernik’s books are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.