There are certain names that are synonymous with the British blues boom of the 1960s. We’ve all heard of the bands that brought the music to the forefront—the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, the Animals, etc.—but before any of those fellows even got started there were dedicated blues musicians slogging it out in the clubs for anyone who’d listen. Some of them—Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies, Graham Bond—were known primarily to devoted London audiences and those who later studied the roots of the music.

And then there’s John Mayall.

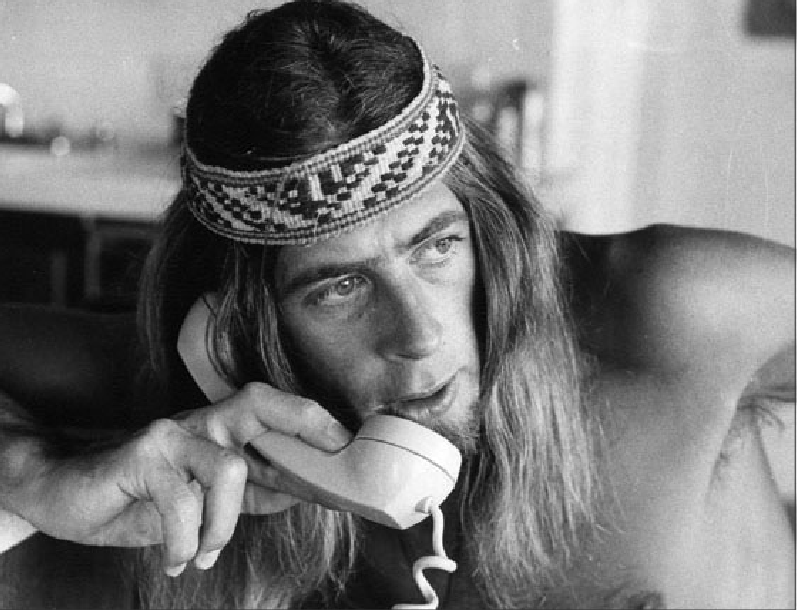

Born on November 29, 1933, Mayall became enamored of blues and jazz early in his life, and he was already performing blues in public by the late ’50s and early ’60s. Signed to Decca Records, the singer/songwriter/guitarist/keyboardist and harmonica player released his debut album, John Mayall Plays John Mayall, in 1965, but it wasn’t until Mayall hired a young guitarist named Eric Clapton away from the Yardbirds that his own band, the Bluesbreakers (sometimes spelled Blues Breakers), began getting noticed on a larger scale. With John McVie on bass and Hughie Flint on drums, the 1966 album Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton also came to the attention of American fans who had been finding their way to blues via those other other British musicians.

Over the next several years, Mayall was a star in America as well as his home country—his tours sold out and his records, including such classics as Blues From Laurel Canyon and The Turning Point—were all over the radio. Mayall never became an arena-level superstar but his bands spawned many of them. In addition to Clapton, he hosted such superior players as Peter Green and Mick Fleetwood (who would both co-found Fleetwood Mac with McVie), Mick Taylor (later of the Stones), Harvey Mandel, Jack Bruce, Aynsley Dunbar and many others.

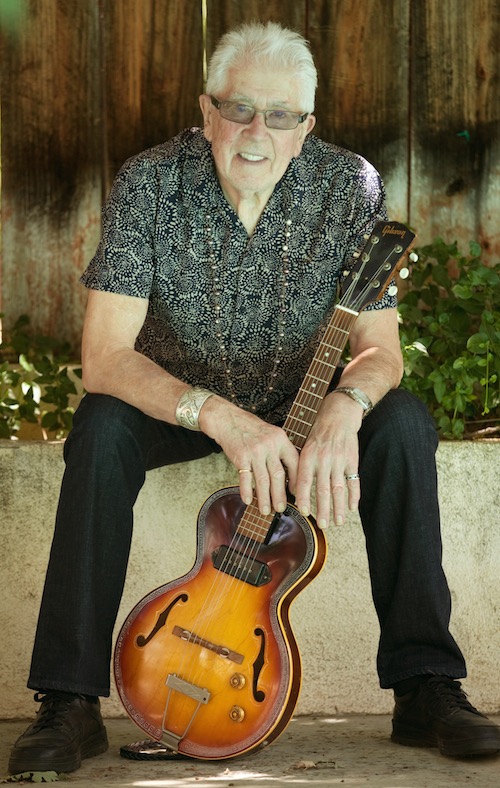

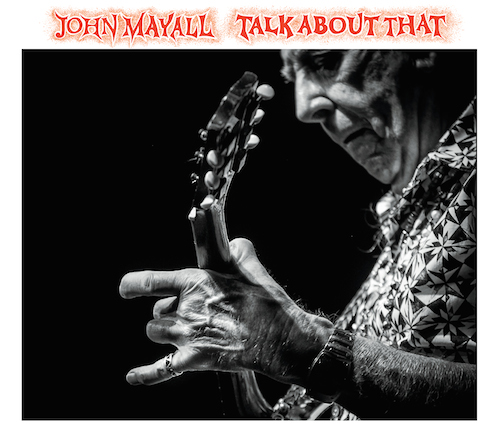

By constantly changing up the lineup, and because of his own insatiable musical wanderlust, Mayall has been able to keep evolving over the years. And he’s still doing it—he released an album in 2017 that ranks among the best of his career, Talk About That (Forty Below Records). By one count his 65th in all, it features new Mayall originals and a few choice covers and finds Mayall accompanied by his longtime quartet of guitarist Rocky Athas, bassist Greg Rzab and drummer Jay Davenport.

After it was finished, however, Mayall decided it was time to shake things up again. He parted ways with Athas and decided to continue with the remaining trio—the first time in his lengthy career that he’s ever worked in that configuration and the first time without a second guitarist. (On the album there is, however, a special guest guitarist who’s been around the block a few times, Joe Walsh, of the Eagles.)

[Since our conversation, he has released a live trio album from 2017, Three For the Road, and a 2022 studio album, The Sun is Shining Down. And after being overlooked for decades, he’ll be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2024.]

We began our wide-ranging conversation with John Mayall discussing the state of his music in recent years.

When you recorded Talk About That, presumably you didn’t know yet that it would be Rocky’s last album with the band.

John Mayall: Exactly, yes. There were no indications of making a personnel change at that time. [The album has] been in the can for a little while. It always seems that I record these albums at a fast pace but they’re put to the test when it comes to getting them released.

Will your next album be with the trio?

JM: It’s too soon to be talking about it but we’ve been having so much fun and creative output when we’ve been doing our live shows as a trio that it’d be the best thing to do, toward the end of the year. We’ll probably do a live album with the trio. That would contain the fireworks that happen on the stage. It would be a contrast with the new album.

What do you like about working with a trio?

JM: There’s so much more interplay. I’m obviously featured a lot more. I play about the same amount of guitar during the course of the set, but it’s a different aspect because I’m not playing duets with another guitar player. That’s always been one of the high points for me, the interplay between me and Rocky. It puts a different slant on things.

The trio actually came about by accident in a way, right?

JM: It was indeed an accident! It just seemed like a great idea and it came together very quickly. It happened so fast that I can’t even remember how it happened. It was during a break between tours; it seemed like a good way to go.

You’ve never been shy about changing things up. Someone counted more than 25 guitarists in your bands since the ’60s. Then there have been numerous bassists, drummers, etc.

JM: Yeah, I’m sort of famous for that, really, though whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing I don’t know. It keeps everything fresh, that’s for sure.

That’s why this latest change is so interesting to us as listeners—I never imagined seeing you without a second guitar player.

JM: That’s the way I feel about it too. It’s put me to the test of being more the focus of things.

Is there a theme that runs throughout the album?

JM: There isn’t an overall theme. Every time I make an album I want to get as many different slants on blues as possible, so it points out to people that blues isn’t just the same thing. We want people to not get bored and to stay with us through to the end. Every track on the album is blues-structured. It’s just a case of finding subject matter that goes with the feel of the song. It wasn’t a great stretch. I wrote the songs probably a week before we got in the studio. I can’t read or write music so unless I’ve got the guys with me, I can’t really do anything about it except trying to remember what I came up with. It’s just blues, and we’ve worked together for so long, so it goes really quick. It becomes second nature if they feel they’ve got something to contribute to a song.

How do you choose your cover material?

JM: I don’t really have a plan. If the song itself resonates with me, that’s the criterion. If I feel that it fits in structurally and emotionally with what we do, then it takes place fairly naturally.

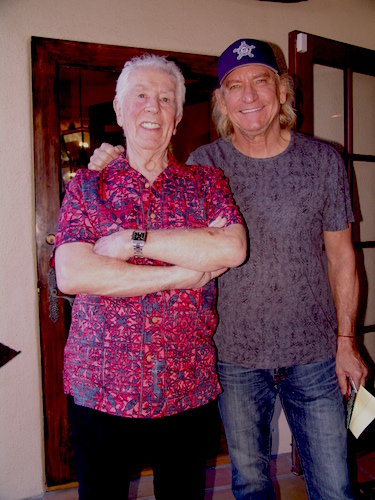

Joe Walsh plays guitar on two tracks, “The Devil Must Be Laughing” and “Cards on the Table.” How did you two get together?

JM: That was a very strange thing. We were in the studio—the band flew in and was only in L.A. for three days—and on the second day, the studio got a call from Joe Walsh. He said he wanted to play with us. He came in the next morning and he was with us for about an hour and a half. I knew nothing about his blues chops—I’d never given any thought to it—but the thought that he wanted to play, it was worth checking out. So he came in and totally nailed it. It was a great surprise to us and a great thrill for him. He totally enjoyed it. He puts an emotional drive into the tunes that he plays on.

Speaking of guitarists, there were three guys in your early bands that everyone always asks you about, and I’m afraid I’m going to be another one to ask. I’m sure you know who I mean.

JM: I can guess, yeah.

Listen to “The Devil Must Be Laughing” with Walsh

Did you know, when you first heard them, that Eric Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor were game-changers?

JM: Well, yeah, the fact that I hired them means I knew they had something special. There was something that set them apart from other guitar players on the scene. And they were available, so I just had to run it by them to see if they’d say yeah. It was kind of a no-brainer. But they were all in the band for a short time, really. It was a very active scene in London in the early days, so it was no big deal that people were in for such a short time. It was a very fertile period in British rock history; there were so many great things that came out of it.

Related: BCB’s review of a Mayall live show from 1967

When you were first coming up, blues and jazz were pretty much mixed together in the London club scene. You were also a big jazz fan, true?

JM: Well, they were so entwined I couldn’t make the distinction and say, “This is jazz and this is blues.” As far as I’m concerned they’ve always been combined, all part of the same thing. It’s all black American music, basically.

Do you ever go back and listen to your early albums? What is your take on them with so much hindsight?

JM: Occasionally I will revisit them to give them a listen. With the fact that we’ll be doing a live album next, which we’ll record during the European tour this year (see itinerary below), we don’t want to repeat songs wherever possible. I want to come up with new things. So I will be checking through the old albums and seeing if any of them translate well for a trio situation. That’s my homework.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton

The Turning Point was a real surprise to us fans because we’d only heard you play with electric bands. Why did you decide to do an acoustic album at that time, in 1969?

JM: For just that reason. I’d been working with the electric guitar, bass and drums format for so long and I felt like a change. Then I had the concept of putting together a band with acoustic guitar, saxophone and no drums. So for me it wasn’t a big deal but the German promoter who’d already booked a tour kind of freaked out. He said, “Why don’t you have the band with Mick [Taylor] do the first half of the show and this weird experiment doing the other one?” He was trying to cover his bets. No one really foresaw how successful it came to be. For me it was just an attempt to do something a little bit different and explore the possibilities. It had its limitations because we only had 10 or 12 songs in the repertoire for all the time we were together, which was just over a year.

In the very early days, after you’d been going for a few years, young bands like the Stones and the Yardbirds came out playing their own take on blues. What did you think of what they were doing?

JM: The Yardbirds were never a favorite of mine. I did see the Stones when they were playing in the small clubs when they were just starting out. They were a very dedicated band and Brian Jones, particularly, I was very friendly with—he and I were very much into the blues, more than the others. We had a great connection. But it was obvious that they had something special.

What was it like for you to play with some of your own blues heroes, like Sonny Boy Williamson and John Lee Hooker?

JM: With John Lee Hooker, he was very easygoing and there was no problem at all. He’d travel around in the van with us for a month, up and down the country. Sonny Boy, I didn’t play very many gigs with him, a specific tour, but he was one of my idols and we did have some time together. When he wanted some new harmonicas from Hohner, he and I drove out there in the taxi, so I got to have a one-on-one with him. He was very nice to me but I don’t think he appreciated the Yardbirds [with whom the bluesman collaborated on a live album] too much. He was OK with me and we did back him up fairly respectably quite a few times.

You’re still so active, especially onstage. What do you do to keep yourself in such great shape?

JM: I think it’s my obligation to give the audience a full-on show with all the energy I can muster. I don’t really have a clue why it happens but I’ll just keep on doing it. For me it’s a big thrill to communicate with audiences and give them what they expect.

You’re a member of the Blues Hall of Fame but not the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Does that bother you?

JM: I can’t really comment on how these things happen, but it’s pretty weird as far as I’m concerned. I’ve remained in the shadows for these big events and big honors, but it’s been going on all my life. It’s no surprise, really, but the upside is that I always have the freedom to do what I want to do musically. Not too many of the more popular groups can say that. They’re trapped in their own success—they have to play the hits. I put together a different set list every night.

What’s your feeling about the current state of blues in general? Is it healthy or getting stagnant?

JM: I don’t think it’ll ever get stagnant. Whenever people say the blues boom is over, then you get another generation of players who come up and give it a huge kick up the butt and appeal to a younger audience. It’s an amazing history and people like Joe Bonamassa and others of his age get a tremendous reaction from young audiences. It’s a music that’s totally a part of our way of life. People will never get fed up with it.

Watch Mayall on the 2017 Rock Legends Cruise with Todd Rundgren

Mayall’s wealth of recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024