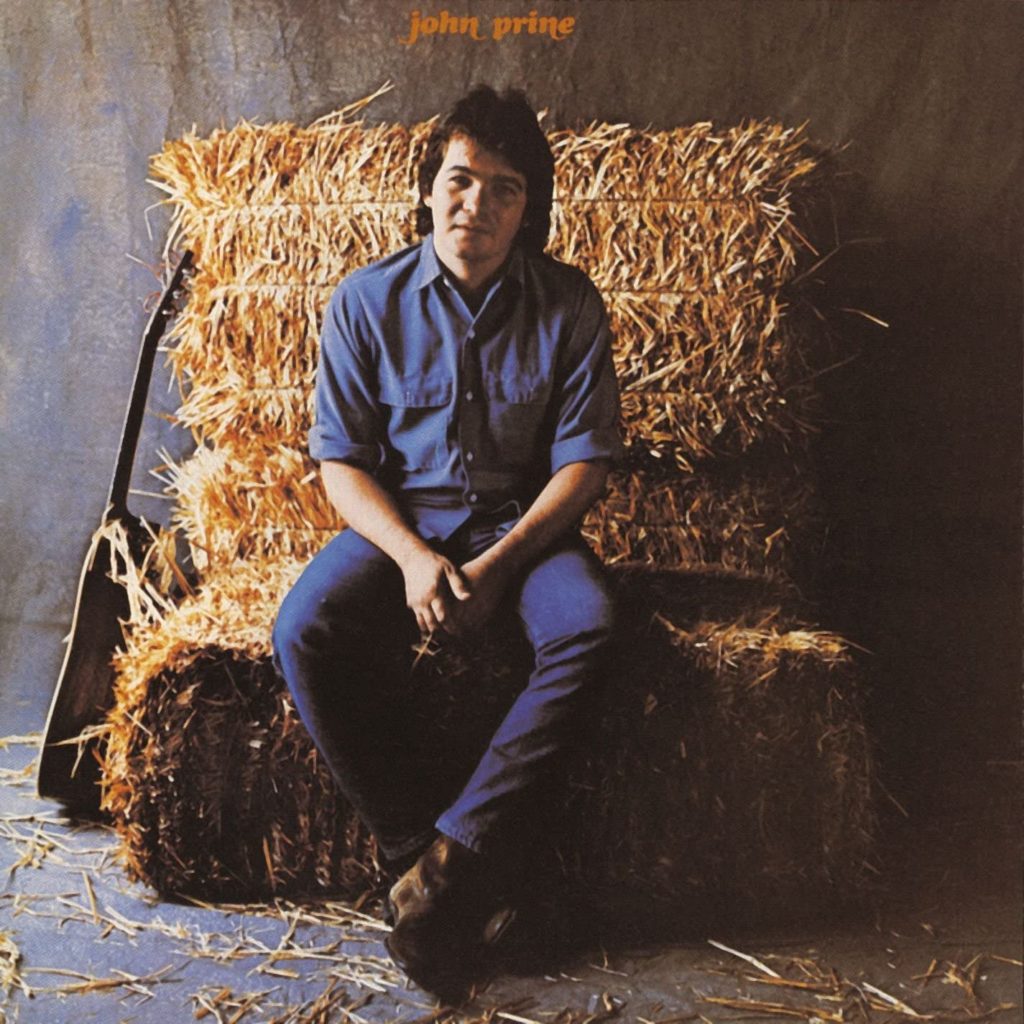

John Prine is a quiet masterpiece, a portrait of a young singer-songwriter already fully formed and crafting songs for the ages on his self-titled 1971 debut album. The Maywood, Ill., native was still learning how to perform for club audiences, building his confidence and strengthening his finger-picked acoustic guitar skills, but his songs were as simple, honest and unvarnished as a hand-crafted Shaker table. “Twenty-four years old and writes like he’s two hundred and twenty,” Kris Kristofferson marveled in his liner notes, a verdict that has been validated again and again in the 49 years since.

John Prine is a quiet masterpiece, a portrait of a young singer-songwriter already fully formed and crafting songs for the ages on his self-titled 1971 debut album. The Maywood, Ill., native was still learning how to perform for club audiences, building his confidence and strengthening his finger-picked acoustic guitar skills, but his songs were as simple, honest and unvarnished as a hand-crafted Shaker table. “Twenty-four years old and writes like he’s two hundred and twenty,” Kris Kristofferson marveled in his liner notes, a verdict that has been validated again and again in the 49 years since.

Still in his early 20s, Prine had learned guitar as a teenager and taken classes at Chicago’s Old Town School of Music while in high school. Upon graduating, he was drafted into the Army, serving his tour of duty in West Germany before returning home and getting a job as a mail carrier. It was while playing local clubs that Kristofferson, in town for his own date, was dragged by opening act Steve Goodman to hear his friend, John Prine. Kristofferson then invited Goodman and Prine to open for him at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village, where Atlantic Records producer and senior exec Jerry Wexler heard Prine and signed him the next day.

Atlantic recognized a world-class songwriter in Prine, yet it also understood he was far from polished as a performer. Taking no chances, the company assigned its most versatile producer and arranger, Arif Mardin, to produce the debut album. Equally adept at creating lush orchestrations and intimate, bare-bones recordings, Mardin resisted any temptation to disguise or smooth Prine’s raw edges, opting instead for lean, open arrangements that would support but never obscure Prine’s voice and guitar. He booked sessions at American Recording Studios in Memphis, assembling a studio ensemble that included members of Elvis Presley’s band, gently prodding them away from their instinctive grooves toward rhythms closer to Nashville than Graceland.

Atlantic recognized a world-class songwriter in Prine, yet it also understood he was far from polished as a performer. Taking no chances, the company assigned its most versatile producer and arranger, Arif Mardin, to produce the debut album. Equally adept at creating lush orchestrations and intimate, bare-bones recordings, Mardin resisted any temptation to disguise or smooth Prine’s raw edges, opting instead for lean, open arrangements that would support but never obscure Prine’s voice and guitar. He booked sessions at American Recording Studios in Memphis, assembling a studio ensemble that included members of Elvis Presley’s band, gently prodding them away from their instinctive grooves toward rhythms closer to Nashville than Graceland.

Under Mardin’s light touch, Prine’s vocals are unvarnished, plainspoken without a trace of vibrato. His slight drawl reflects his family’s roots in Western Kentucky, as do the songs’ familiar chord progressions and simple meters, which echo folk and country songs decades if not centuries old.

Side one of the original LP is a slow-release triumph, six songs that draw listeners in with two gently surreal broadsides against conformity. “Illegal Smile” offers a speed sketch of daily tribulations, then winks at a “key to escape reality” inescapably heard as an ode to cannabis, despite Prine’s later disclaimers. “Spanish Pipedream” offers a shaggy dog seduction and an invitation to “blow up your TV, throw away your paper/Move to the country, build you a home,” extending a sense of amiable whimsy.

And then, Prine gets serious.

“Hello in There” reveals empathy as his superpower. With precise yet conversational details, he evokes an elderly couple surveying the landscape of their lives—children sired, then grown, then lost, as their own world grows desolate in its isolation. In its final verse, Prine challenges the listener to reach out rather than retreat when they see “some hollow, ancient eyes.” An elegy for the elderly in an age of youth culture, the song would become a standard for labelmate Bette Midler. Its glimpse of mortality identifies a common denominator in many Prine songs, what Bob Dylan has praised as “pure Proustian existentialism” in the “Midwestern mindtrips” of his characters.

With “Sam Stone,” Prine brings Vietnam home, doing more to personalize that war’s needless carnage than any straightforward protest song. Sam is a wounded ’Nam veteran with shrapnel in his knee and a collateral addiction to morphine. Its chorus is offhand and harrowing: “There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes/Jesus Christ died for nothin’, I suppose…”After returning to a “welcome home [that] didn’t last long,” his decline points only toward oblivion. First heard when U.S. troops were still embroiled in that war, returning home to scorn more often than gratitude, “Sam Stone” was years ahead of public acceptance for the price paid by its veterans.

Prine then follows the pathos of “Hello in There” and the squalid tragedy of “Sam Stone” with a requiem for a lost way of life drawn directly from his family’s history. “Paradise” recounts childhood trips to his parents’ birthplace in Muhlenberg County, “down by the Green River where Paradise lay,” asking to return to that heartland only to be told it’s gone:

“Then the coal company came with the world’s largest shovel

And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land

Well, they dug for their coal ’til the land was forsaken

Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man…”

With its graceful waltz-time rhythm, precise imagery and a chorus structured as a conversation between child and parent, “Paradise” echoes traditional Scots-Irish-English ballads imported by 17th and 18th century immigrants to Appalachia, where they became the root stock of country music. That the topic is modern environmental destruction amplifies the contrast between a remembered rural Eden now ravaged.

“Pretty Good” reels us back to the present day in a laid-back blues spiced with terse electric guitar accents, as Prine ambles through a series of surreal, deadpan encounters that invited Prine’s membership in the “new Dylan” club invoked by ’70s critics. Prine uses his chorus’ title hook to good effect, rating each new event as “Pretty good, not bad, I can’t complain/But actually, everything is just about the same.”

“Pretty Good” reels us back to the present day in a laid-back blues spiced with terse electric guitar accents, as Prine ambles through a series of surreal, deadpan encounters that invited Prine’s membership in the “new Dylan” club invoked by ’70s critics. Prine uses his chorus’ title hook to good effect, rating each new event as “Pretty good, not bad, I can’t complain/But actually, everything is just about the same.”

By this point on his debut, Prine had already banked enough classics for at least two albums, but John Prine took out insurance with seven more tracks, all solid at minimum. “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven Anymore” again invokes the Vietnam conflict, this time using oblique humor to make its point. “Donald and Lydia” takes us into the dream lives of two lonely misfits and an imaginary romance in which they “made love from 10 miles away.”

Related: Prine’s 2018 intimate concert of stories and songs

Any suspicion that Prine might have front-loaded the LP with his best songs disappears with the ninth track, “Angel From Montgomery,” in which Prine transcends time and gender to become “an old woman named after my mother,” describing a barren life in bitterly unsparing detail. A darker, first-person companion piece to “Hello in There,” the song would be covered three years later by Bonnie Raitt, for whom it would become a signature ballad and just one of many Prine songs that would invite countless covers in the decades that followed.

John Prine barely cracked the album charts, establishing a modest but fiercely loyal fan base noteworthy for its head count of fellow musicians as his influence on three generations of songwriters has only grown. Peers like Kristofferson, Dylan, Johnny Cash, Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen have been joined by alt-country stars in the ’90s and country, American and rock acolytes including Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson, Miranda Lambert, Kacey Musgraves and Brandi Carlile. Prine’s death from the COVID-19 novel coronavirus on April 7, 2020, unleashed a global tide of mourning and appreciation attesting to an impact far beyond any simple commercial calculus.

Bonus Video: Watch Bonnie Raitt and John Prine sing “Angel from Montgomery” on the 18th American Music Association Annual Honors

Watch Johnny Cash cover “Sam Stone”

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024

1 Comment

Thanks for this and thank you John. You sure got my attention. You made all look so damned easy.