As Johnny Cash prepared to perform his soon-to-be classic “Cocaine Blues” at San Francisco’s Carousel Ballroom on April 24, 1968, he offered an introduction that is fascinating in its matter-of-factness: “Here’s another song from the show we did at Folsom Prison. It’s in the album that’s out next week.”

As Johnny Cash prepared to perform his soon-to-be classic “Cocaine Blues” at San Francisco’s Carousel Ballroom on April 24, 1968, he offered an introduction that is fascinating in its matter-of-factness: “Here’s another song from the show we did at Folsom Prison. It’s in the album that’s out next week.”

In that instant, nobody at the Carousel—not Cash nor his Tennessee Three, not the show’s legendary soundman Owsley “Bear” Stanley, nor the 700 or so hippies in attendance—could have known that casually referenced live album would become one of history’s most illustrious and influential.

As Cash historian Mark Stielper has noted, this version of “Cocaine Blues” underscores the Carousel show as “the last picture of Cash before he was a prophet and a pilgrim and mover of mountains and a friend of presidents and the voice of God.” And, in this way, adds a wholly new chapter to the story of Cash’s redemptive rise that’s so extraordinarily documented on At Folsom Prison and At San Quentin.

Adding another layer of singularity to the recording is the sonic touch of Bear, the live sound pioneer and ’60s counterculture icon known as the architect of the Grateful Dead’s “Wall of Sound.” While seemingly an unlikely pairing with Johnny Cash, Stanley delivers a mix that’s been described as “probably the closest to what it actually sounded like to be in the audience for a Johnny Cash show in 1968.”

Featuring Cash entirely on the right channel and the Tennessee Three all on the left—a decision even Starfinder Stanley, Owsley’s son, admits is “a bit weird until your brain adjusts”—he sets the listener right between Cash and his band, as if they were center stage at the Carousel that evening. It’s a testament to the unconventional genius of a sonic innovator whose avant-garde techniques are accepted as gospel today.

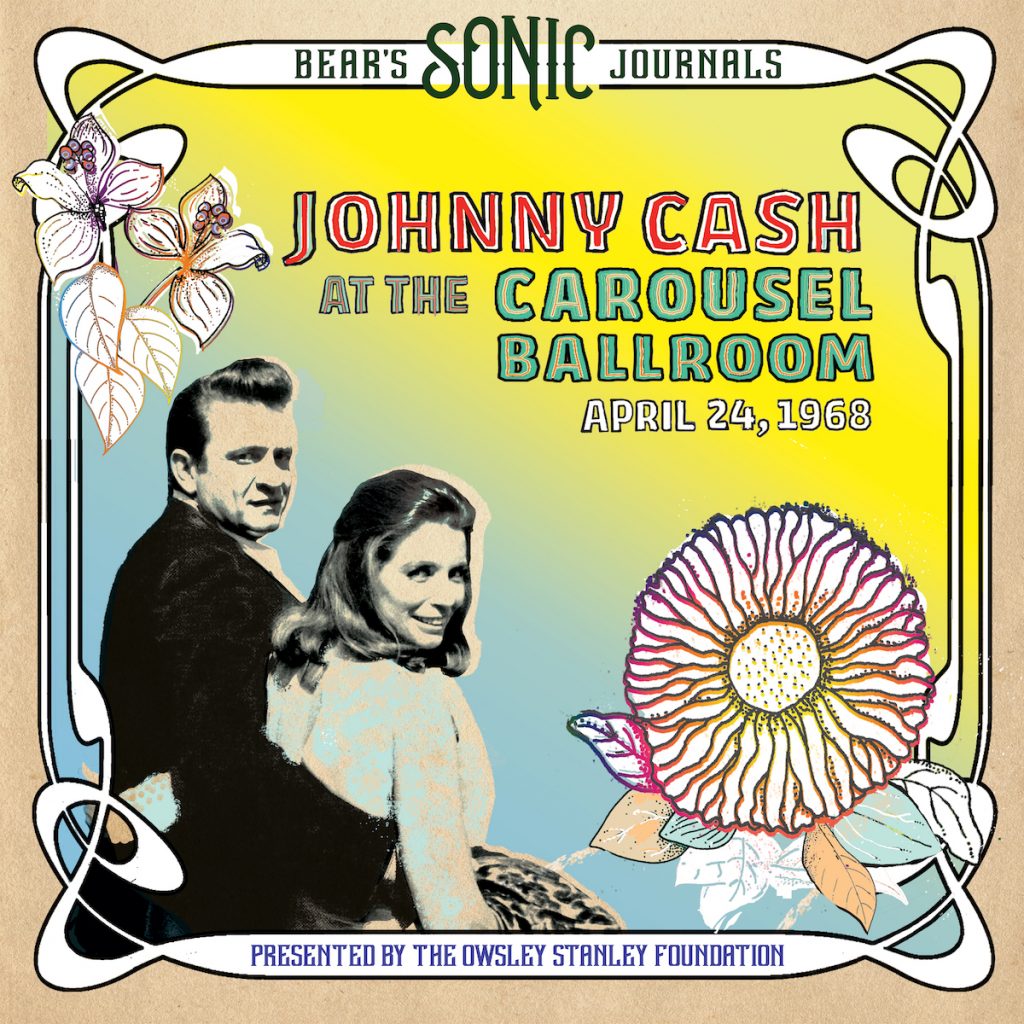

Johnny Cash at the Carousel Ballroom was released in 2021 by Renew Records/BMG/Legacy Recordings.

The package contains new essays by Johnny and June Carter Cash’s son John Carter Cash, Starfinder Stanley, the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, and Widespread Panic’s Dave Schools, as well as new art by Susan Archie, and a reproduction of the original Carousel Ballroom concert poster by Steve Catron. It’s a collaboration of the Owsley Stanley Foundation and BMG.

This release marks another entry in the Owsley Stanley Foundation’s “Bear’s Sonic Journals” series, which has previously included Stanley’s live recordings of the Allman Brothers Band, Tim Buckley, Doc & Merle Watson, New Riders of the Purple Sage and many more.

Cash’s personal life was on the upswing at the time he played the Carousel, although it wasn’t entirely obvious—yet. He’d just married the love of his life, June Carter. He had temporarily conquered his drug problems. In just two weeks, Columbia Records would ship Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison to retail outlets. The next year he’d command an ABC-TV show, which helped him become an American icon.

But on April 24, 1968, his career was in transition, which meant that when he got an offer to tack a last-minute date onto the end of his tour at a hippie ballroom in San Francisco, he took it. Mother Maybelle Carter and the Carter sisters had already gone home; it was just John, June, and the Tennessee Three: Luther Perkins, electric guitar; Marshall Grant, bass; and W.S. Holland, drums, booked on a Wednesday night.

Since it was a slightly different room and an open-minded audience, Cash felt free to vary things. In addition to all his usual songs, he covered two Dylan songs (“Don’t Think Twice,” “One Too Many Mornings”) and one of his greatest but less frequently performed songs, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

And Bear taped every note. The Carousel Ballroom’s resident sound man and recording whiz recorded the show in a way, says his son, that makes you “feel as though you’re on the stage.”

As a bonus, we also get to hear June Carter Cash, the star’s wife. Before joining forces with Johnny, both professionally and personally, she had played guitar and sung on Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry for 17 years. She had appeared with Johnny on stage since 1961. At the Carousel show you hear her vocals, guitar work and the sweet harmonies she shares with Johnny.

On August 16, 1975, in Anaheim, California, 40 miles from Los Angeles, this writer interviewed Johnny Cash for the now defunct Melody Maker. He was in Southern California to promote his autobiography, Man In Black, and to perform a special concert for the Christian Booksellers convention.

I spoke with Johnny about the new popularity of country music. Cash and other country music stars now headlined bigger venues and their records were heard more frequently on both the AM and FM radio dials.

“One reason country music has expanded the way it has is that we haven’t let ourselves become locked into any category. We do what we feel,” reinforced Cash. “I like to go into the studio with my own musicians and record my own songs. I’m open to other songwriters. I like to do things different all my career.”

I asked Johnny about Bob Dylan. “I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963,” he said. “I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with. I was in Las Vegas in ’63 and ’64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence.

“We finally met at Newport in 1964. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He’s unique and original. I keep lookin’ around as we pass the middle of the ’70s and I don’t see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn’t diminished. I get inspiration from him.”

The respect was mutual. In the revealing 2009 book A Heartbeat And A Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears by Antonino D’Ambrosio, country singer Johnny Western remembered witnessing a Dylan and Cash exchange where Dylan admitted, “Man, I didn’t just dig you; I breathed you.”

Related: And then there was the time Cash sang with the Monkees

Cash’s significant recorded legacy is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.