Any worthwhile Kiss discussion begins with the visual. Imagery, after all, is the trait that set the band apart in its early years, when its icon-themed kabuki makeup made the band a marketing sensation well out of proportion with its music’s actual commercial appeal. Those same visuals, long discarded for an era that opened with 1983’s Lick It Up, also were a key factor when restored for a 1996 original-lineup-reunion tour that revived the band’s long-decayed fortunes, and opened a new run of viability. As much as any song, look is the essential element of Kiss’ identity and longevity.

Any worthwhile Kiss discussion begins with the visual. Imagery, after all, is the trait that set the band apart in its early years, when its icon-themed kabuki makeup made the band a marketing sensation well out of proportion with its music’s actual commercial appeal. Those same visuals, long discarded for an era that opened with 1983’s Lick It Up, also were a key factor when restored for a 1996 original-lineup-reunion tour that revived the band’s long-decayed fortunes, and opened a new run of viability. As much as any song, look is the essential element of Kiss’ identity and longevity.

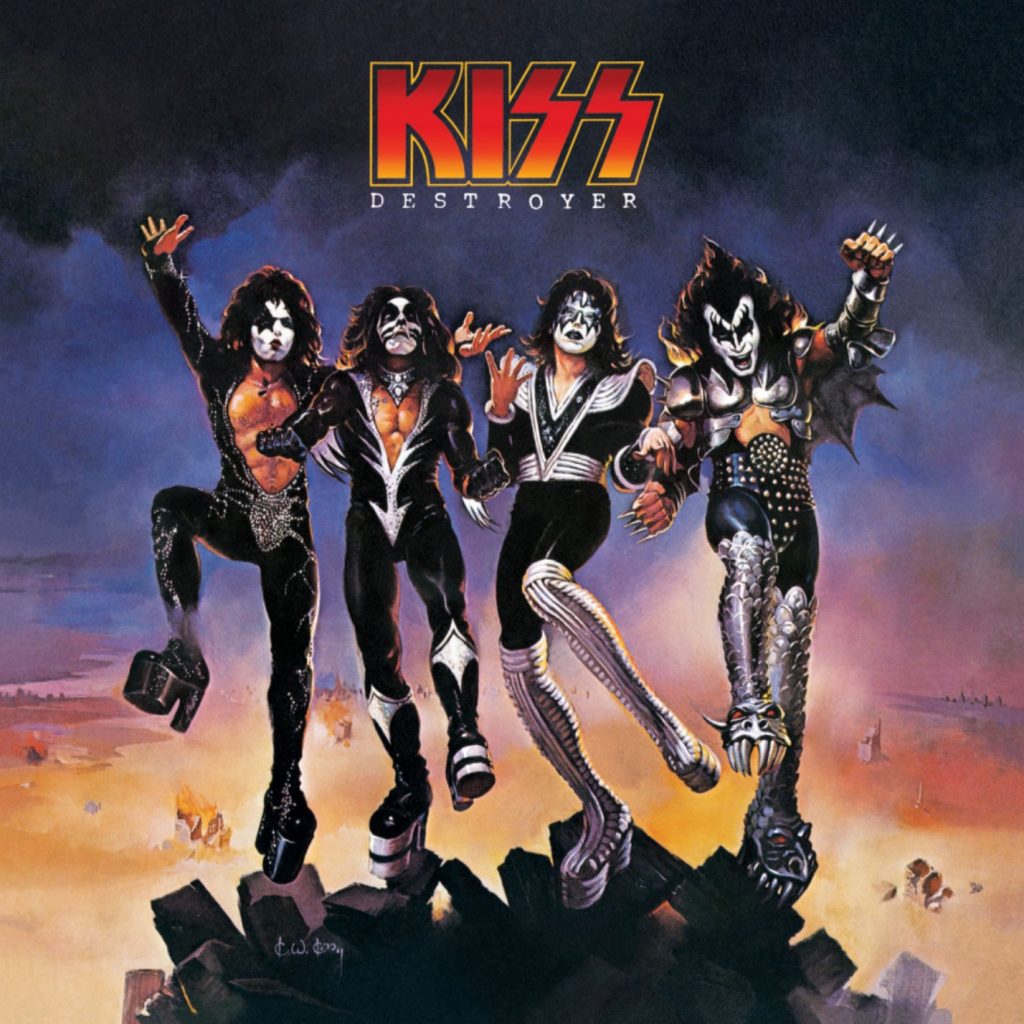

When the quartet released its fourth studio record (and fifth album overall) in 1976, Destroyer marked a wise evolution of its album-cover aesthetic; where the group’s first four records had used photos of the band in its makeup and costumes (with the suits on 1975’s Dressed to Kill an amusing change of pace), Destroyer transformed the band into the comic book characters they had on some level always been, with a cover painting by fantasy artist (and Frank Frazetta nephew) Ken Kelly. Set against an evocative flame-and-mists backdrop (though less evocative than the destruction-plagued landscape in Kelly’s label-rejected original version) and presenting the four bandmates as larger-than-life characters, the result was an all-time-great rock and roll cover with an upgraded aesthetic that, it turns out, echoed the contents of an album that featured plentiful decorative atmosphere in its own right.

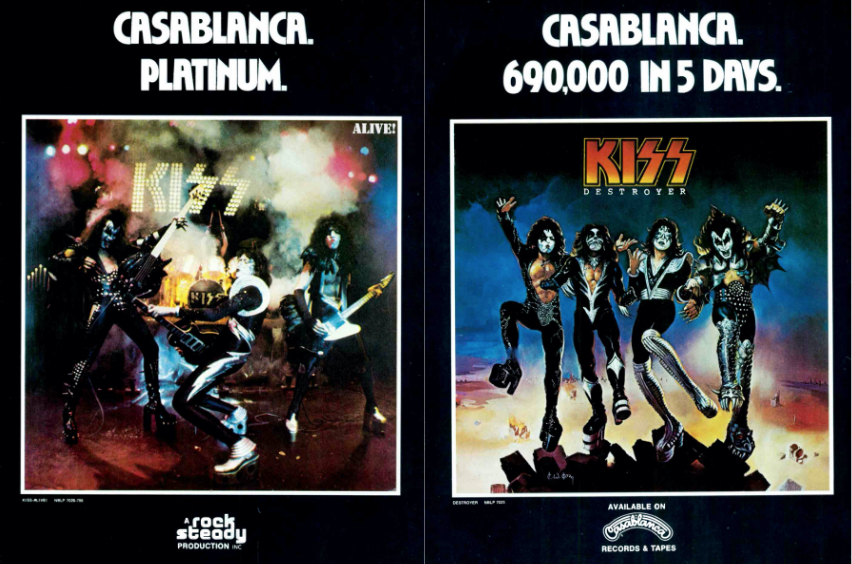

The year 1976 found Kiss at a positive turning point. Dressed to Kill had been a spit-and-bailing-wire operation from a label short on cash, with Casablanca Records so broke that label head Neil Bogart produced the record to avoid paying an outsider. Then came the group’s two-disc live (with major overdubbing) collection Alive! later the same year, which reached the top 10 on Billboard’s album chart and pulled Casablanca away from the yawning chasm of bankruptcy, not to mention netting Kiss a new deal that paid them $15 million up front. For their next album, there would be no home-cooked overseer.

Enter Bob Ezrin, fresh off his success with Alice Cooper on Welcome to My Nightmare, a commercially successful concept record built for theatricality and arch excess. Those same qualities translated neatly to the Kiss paradigm, and his arrival marked a breakthrough for the band in delivering a sonic experience that matched the dramatic elements of its look.

Ezrin’s presence is felt immediately on the record, and not only because he doubles as a news reader amid the effects preamble that kicks off side one. It’s nearly 90 seconds of screeching tires and car stereos (blaring the then-recent hit “Rock and Roll All Nite,” naturally) before the band shows up, leaping in with the crisp chug of “Detroit Rock City.” Propelled by the interlaced dual electric guitars of Ace Frehley and Paul Stanley and gilded by a repeating bass lick from Gene Simmons, the song is a roaring slab of rock bombast where Stanley’s echo-trimmed wail is right at home. The track would be offered as the album’s third single to lukewarm reception, though that 45 would find new life thanks to its flipside…but more about that in a bit.

“King of the Night Time World” wasn’t a Kiss original, but the Hollywood Stars cover is right in their wheelhouse with its up-front mélange of braggadocio and raw come-on fused into an insistent throb. Had they written it themselves it might have had a somewhat different structure, given the trouble its mid-song time change gave drummer Peter Criss, but its unashamed blasts of self-aggrandizing cliché, dressed with Stanley’s decorative, grit-lined solo, land the whole affair right up the band’s alley.

Fascination with the darkly fantastical was one of the band’s driving creative forces from its early days, and it shows in the plump, melodramatic “God of Thunder,” a song so serious that it cannot be serious. It is first-draft bluster, ridiculous and excessive—Simmons’ hammy chorus growl is a severe reminder of his limits—but its brutal earnestness demonstrates how valuable committing to the bit always was for this act. The guitar and drum adornments in its sludgy slog are overdone, but with those flavors added to an Ezrin keyboard line and random vocal bits from his two sons, the assortment does go some way toward obscuring the number’s fundamental shortcoming—that it paints its shadowy images with a dearth of imagination.

On the other hand, there’s “Great Expectations,” an opportunity for Simmons to spread his (bat) wings that Ezrin dolls up in spectacular fashion. Although at its core it’s about what nearly all Kiss songs are about—the looming prospect of sex with Kiss—there is real ambition in folding elements of Beethoven’s “Sonata No. 8” and support vocals from the Brooklyn Boys Choir into a song in which Simmons reminds everyone yet again of his tongue’s capabilities, proudly noting, “You see what my mouth can do.” Undeniably overcooked, the song also is oddly ingratiating, an anything-goes explosion of nonsense that adds up to an intriguing absurdity.

Ezrin’s impact is heard everywhere, including in his enlistment of Lou Reed/Alice Cooper alumnus Dick Wagner for the uncredited guitar lead in “Sweet Pain,” which inserts flair behind a Simmons lead vocal in a ramrod of a tune and dresses up an otherwise bludgeoning anthem. Wagner also appears without portfolio in “Flaming Youth,” a stew of an arrangement in which Ezrin took pieces of individual songs by Frehley, Simmons and Stanley and assembled them into one while adding his own touches, among them a whiff of calliope beneath a repeating refrain. Offered as a second single that stalled at #74, the song features one of Stanley’s stronger vocal moments on the record, driving its rebellious message in a manner considerably less cartoonish than many of his utterances, though his final yelp of “higher” near the end gets pretty close.

The album’s production gives it cohesion and adds depth in places to what would otherwise be wholly forgettable. The album-closing “Do You Love Me” leavens typical Kiss bloviation with a touch of neediness, but outside of the courage of its convictions, its charms are highly suspect.

In some ways its lack of a convincing hook makes necessary the “hidden” final track that follows, the spacey instrumental “Rock and Roll Party,” if only because it closes the album with something that, while random-sounding, dissipates any lingering staleness from what preceded it.

Destroyer reached stores March 15, 1976, just two weeks after the release of its first single, “Shout It Out Loud.” The closest thing to a party anthem the record had to offer, it was a logical candidate to replicate the success of “Rock and Roll All Nite.” Featuring an atypical lead vocal duet from Stanley and Simmons, its propulsive bluster suited both of their styles. Matched with a thick electric guitar swath and fills that drive home Criss’ rattling drums, it is a grabby set piece in which all of the band’s components coalesce. By the time that the Bicentennial summer of ’76 rolled around, it appeared that its climb to #31 on the singles chart—and its chart-topping performance in Canada, the band’s first time to achieve that anywhere—would be the album’s signature success.

Related: 20 years after Destroyer, the original members of Kiss reunited

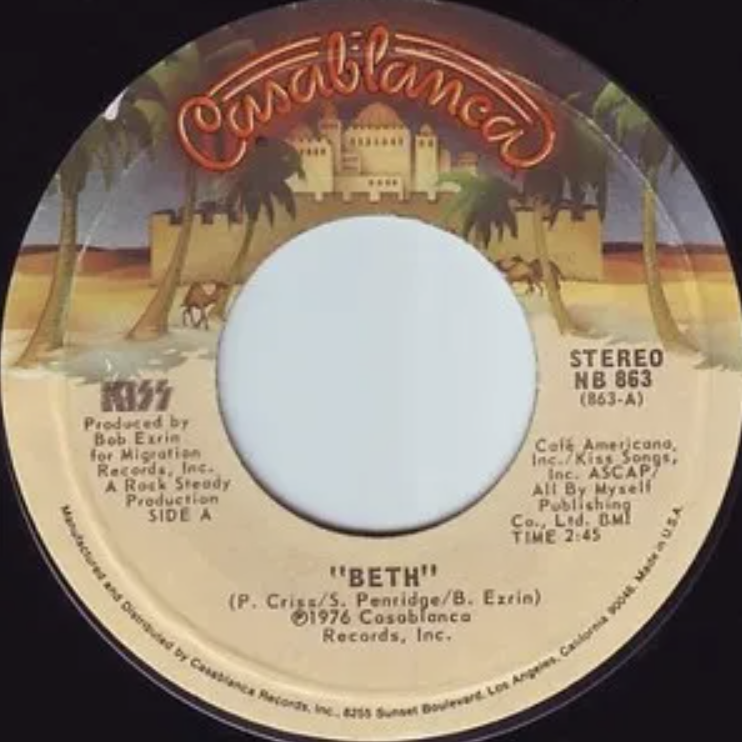

But then came “Beth,” and its unlikely road to success. A song Criss had co-written with his friend and former Chelsea bandmate Stan Penridge years before (with the title “Beck,” another detail that demonstrates Ezrin’s impact), he offered it to the band and found a willing collaborator in his producer. The finished song features a lovely (and again uncredited) Wagner acoustic guitar line, Ezrin’s piano, and substantial help from 25 members of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Criss provides the lead vocal, and while craggy and indicative of the narrow palette at his disposal, it is arguably the most memorable vocal performance on any Kiss song.

The rest of the band had little use for it, and in fact it’s the only song in the band’s catalog on which none of the primaries plays an instrument. Kiss manager Bill Aucoin would later claim Simmons and Stanley wanted it kept off of Destroyer, and that it was saved only by his intervention.

Bogart didn’t do the song any favors either. Casablanca’s head was dismissive of the track, and despite receiving advice that it had the potential to be a hit, he demanded (because, it has been claimed, his ex-wife’s name was Beth and he thought it played up elements of their marriage crumbling) it be torpedoed by making it the B-side of “Detroit Rock City.” As it turned out, radio discovered the song there, and started playing it. A month after the initial July release of “Detroit Rock City,” the single was reissued, with “Beth” now the A-side and “Detroit Rock City” relegated to the flip, and from there, it became a sensation.

Bogart didn’t do the song any favors either. Casablanca’s head was dismissive of the track, and despite receiving advice that it had the potential to be a hit, he demanded (because, it has been claimed, his ex-wife’s name was Beth and he thought it played up elements of their marriage crumbling) it be torpedoed by making it the B-side of “Detroit Rock City.” As it turned out, radio discovered the song there, and started playing it. A month after the initial July release of “Detroit Rock City,” the single was reissued, with “Beth” now the A-side and “Detroit Rock City” relegated to the flip, and from there, it became a sensation.

“Beth” would climb as high as #7—to this day the highest any Kiss single has charted—while going on to sell a million copies and helping light a fire under Destroyer’s sales, which had to that point been soft. It also became one of the band’s signature tunes, much to the chagrin of at least three in the quartet. Simmons and Stanley have both made a point of speculating that Criss was incapable of writing the song, and to this day its performance at Kiss shows sees everyone else leave the stage when the guy in cat makeup (these days it’s Eric Singer) comes out from behind the drum kit to sing to a prerecorded track. None of that ill will—and this is a band in which hard feelings are historically easy to come by—changes the song’s immense success, nor the benefits it has provided the band while earning a lasting reputation as a classic power ballad.

Listen to the live version of “Beth” from the L.A. Forum in 1977, released on the Alive II album

Two months after “Beth” reached its chart peak, Destroyer became the first Kiss album to achieve platinum sales, a feat the band would soon replicate with its next album, Rock and Roll Over, which arrived in November of the same year. Ezrin would depart for that set, replaced for the next few projects by returning Alive! producer Eddie Kramer (including 1977’s Love Gun, with another iconic Kelly cover). Along the way, the band continued to follow the path established on Destroyer, manufacturing music with an ear toward more involved, refined production that, even if it couldn’t quite compare, could somewhat pay off expectations created by the array of spit blood, flaming guitars, explosive chest hair and, yes, freakishly protracted tongues found in its stage spectacles.

Kiss’ extensive recording catalog is available here.

4 Comments

“Destroyer became the first Kiss album to achieve platinum sales.”

Not so. “Alive!” was their first platinum album.

Everybody I knew back then owned Kiss Alive!!!!!! I wore out my first copy!!!!!

“Alive!” was certified gold in December 1975…and to this day has not been certified platinum.

Kiss was the greatest. No pretensions. The perfect embodiment of Frank Zappa’s declaration, “We’re only in it for the money!”

The intro to “Detroit Rock City is hilarious. It’s “D.O.A.”, but with the narrator sucking helium.