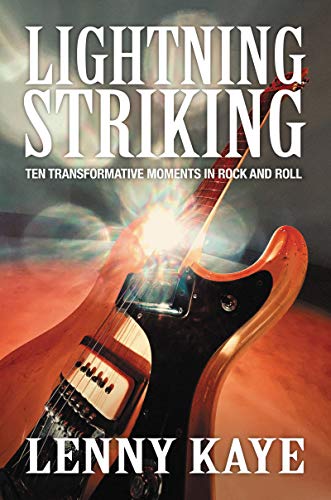

In his latest book, 2022’s Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments in Rock and Roll (Ecco), author Lenny Kaye takes a different tack than those rock historians whose tomes have preceded his. While Kaye does necessarily follow a timeline, his chronology meets up with geography, the music’s story diced up into chapters that elucidate the genesis of the various “scenes” that defined rock’s growth over its first four decades.

Following a brief introductory teaser that sets down in Cleveland in 1952—where disc jockey Alan Freed first scared the bejesus out of white parents by bringing the newly developing, exciting African-American music called rhythm and blues to their kids—we travel through the Memphis of 1954, where Elvis Presley made this new sound his own, and then on to New Orleans 1957, Philadelphia 1959, Liverpool 1962 and further onward, with stops in San Francisco (1967), Detroit (’69), the London of the 1977 punk era, the melting pot that was New York in the mid-’70s, L.A. and Norway (yes, Norway, a breeding ground for metal) in the ’80s and ’90s, and finally Seattle 1991, where Nirvana and Pearl Jam ignited what Kaye suggests may have been rock’s final seismic eruption.

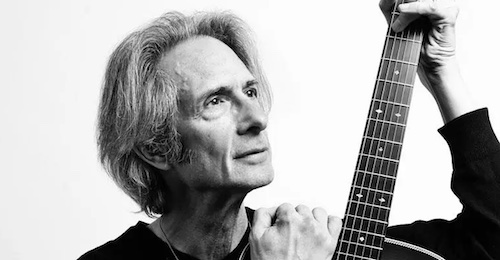

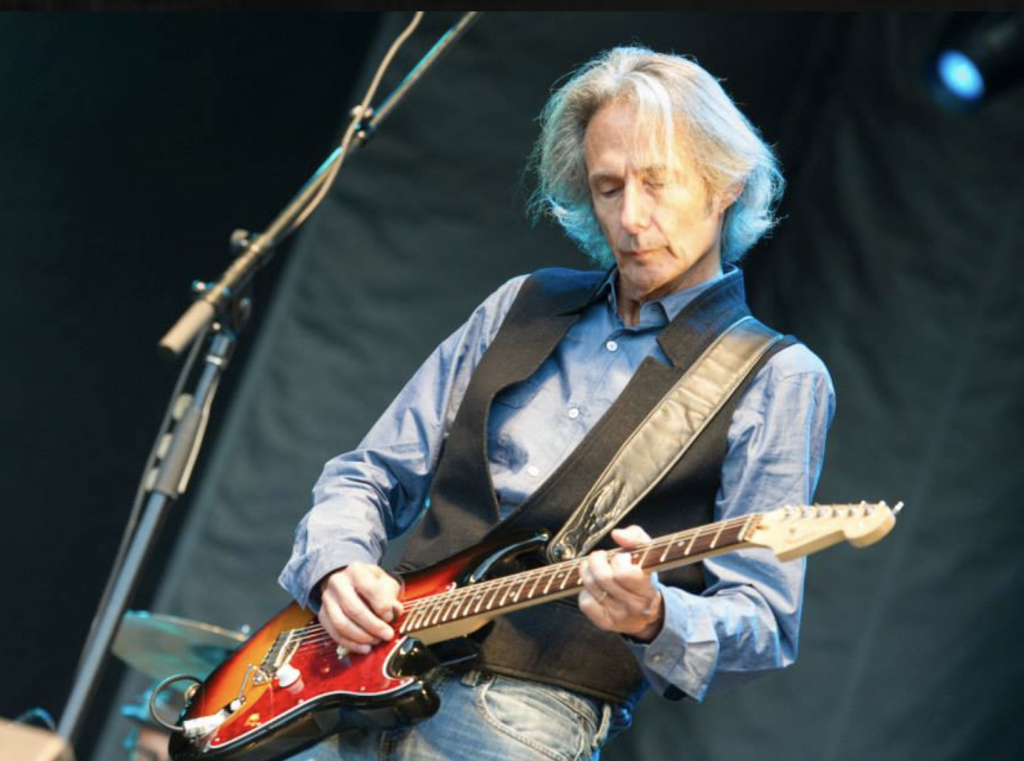

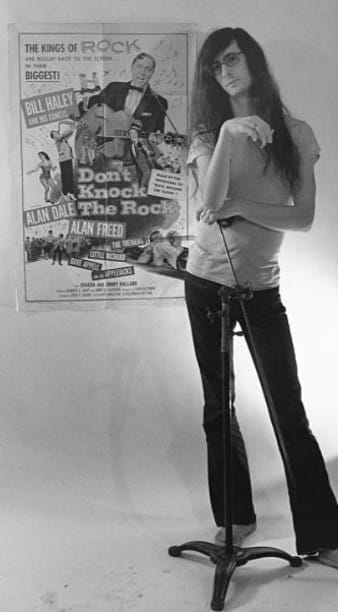

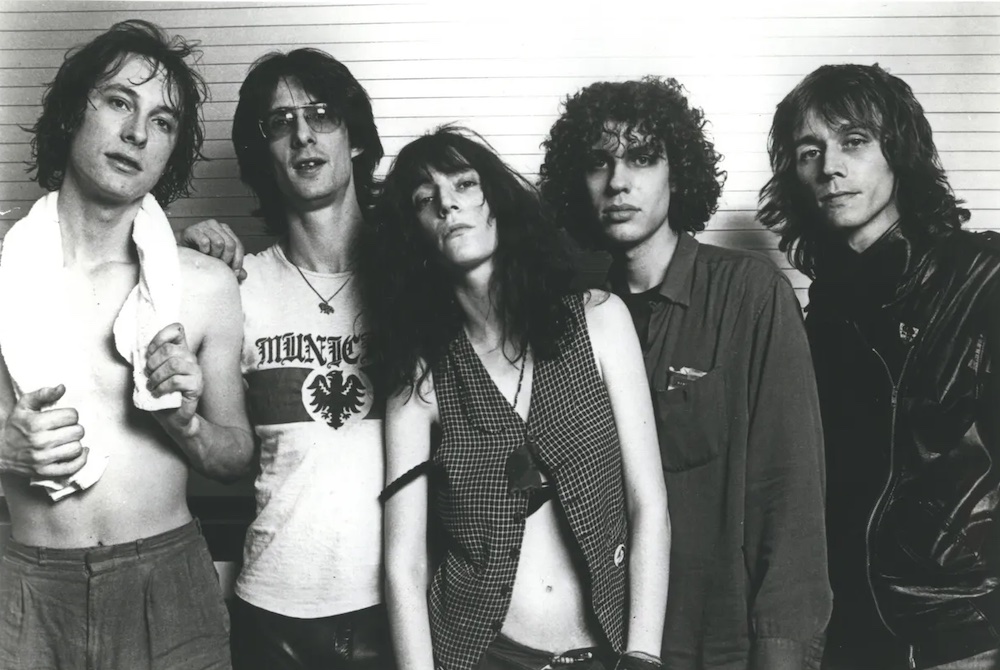

The book is meticulously researched but never does it take a staid, academic tone. Kaye’s writing is ebullient and inspired, and also a whole lot of fun. It’s breezy while being informative and insightful, and it benefits from Kaye’s insider perspective: He’s not only been a huge fan of the music nearly since its birth, he’s also been a center-stage participant, during his younger days as a record store clerk and music journalist and then, beginning in the early ’70s and continuing to this day, as guitarist in Patti Smith’s various bands. Kaye, born Dec. 27, 1946, integrates himself into the chapters not as an ego move but because he was actually there, at the heart of it all, and the tale benefits from his first-person accounts.

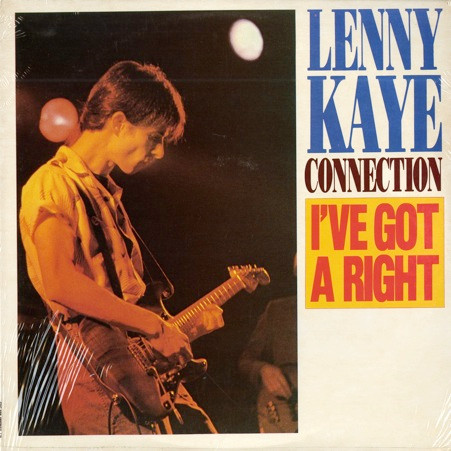

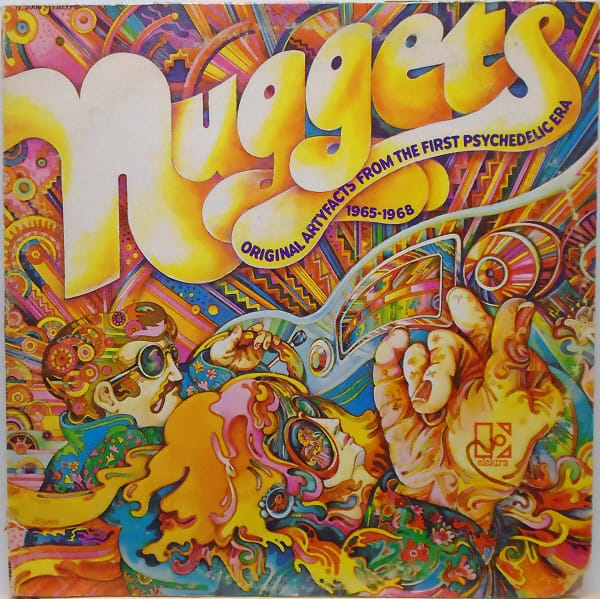

We spoke with Lenny Kaye in 2022 about Lightning Striking (whose title plays off a 1966 Lou Christie hit), his long association with Smith, his curation of the game-changing Nuggets compilation album of primal psychedelic singles in 1972 and why he remains an avid collector of real records, a champion of vastly diverse music from the past and an optimistic cheerleader for music’s future—whatever it turns out to be.

Best Classic Bands: You expected to spend a couple of months writing each chapter of Lightning Striking but it actually took you about three times that. Why?

Best Classic Bands: You expected to spend a couple of months writing each chapter of Lightning Striking but it actually took you about three times that. Why?

Lenny Kaye: I wanted to tell the story of each of these moments in time as completely as I could. It was fun—you get a chance to investigate all the tangents and minor characters and strange happenings. Even though you really think that you know what was happening in each, once you get deep in it, you realize that each of the chapters could probably be a book. That’s the nice thing about music, at least our music, rock and roll.

Why did you approach rock history as a progression of different scenes that emerged in American and European cities?

I’ve always wanted to do a history of the music, but that’s an infinite topic. But in looking over the landscape, or the soundscape, of the music, you could see that there were certain peaks that happened over the course of rock and roll’s long history. I thought that this would be an interesting way to tell the tale, as well as emphasizing what I really like about rock and roll, which is the local, the grass roots, how things start, and where they go to. I just embarked on a journey. There were other places I might’ve stopped.

Like where? Which places did you leave out?

You could do a whole thing on Chicago blues. The two chapters that were in the original proposal that I didn’t get to, for reasons of time and space and energy, were an alt-rock chapter from the’80s, taking on Athens, Georgia, and Minneapolis. And I wanted to end the book in Manchester in the ’90s, with the Factory [Records] scene, bands like Happy Mondays. But I feel that the ones that I chose were central to the times when rock and roll ascended the ladder of its evolution. I didn’t really want to do major music business capitals; the ones I chose were really underground scenes. I like when things start coalescing around a new idea and a way of doing things.

Why did distinctly disparate styles of music emerge from specific locations? The rock of Detroit in 1968 was fundamentally different than that of San Francisco around the same time.

Especially in those pre-internet times, there could be a very local sensibility happening. I’m not sure if that’s still the case now. Now, all I do is tap a computer key and I’m there. I think that the fact that scenes were able to develop regionally helped make them unique and noteworthy. Energy gathers in a certain moment in time and space. Sometimes these things happen really quickly and render obsolete what came before. Overnight, Elvis Presley in Memphis rendered an entire pop music old-fashioned, in the same way that grunge overtook hair metal [in the early ’90s]. Sometimes the channel changes very quickly, and I find that kind of exciting. I was filtering it through my own aesthetic. My story, as a writer, musician, and most of all a record fan, a fan of the music, runs parallel. So I chose those moments in time that changed me. It’s a very personal, weird perspective. But I never had any desire, or have a desire, to write a memoir.

But in a way, you did anyway, because once the book moves into the ’60s and ’70s, you start weaving in your own story—especially once you join up with Patti Smith.

I like being on the sidelines and seeing what place I had within it. I traveled to San Francisco in [the late ’60s] and I talk about why I did that. But that’s not the main story. The main story is the bands that were there, the bands that were on my teenage wall—Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Grateful Dead—and how their ripples in the pond would affect me as a musician and as a participant in the scene that I, by good fortune, became a part of in New York in the mid-’70s.

And now, decades later, somebody, somewhere, has a poster of the Patti Smith Group on their wall. And a kid somewhere is studying your guitar licks. You became that guy, being idolized, just as you idolized others when you were first encountering rock and roll.

And hopefully that influences them to create the next step in whatever. It’s the evolutionary process. I like that sense of carrying the torch. I know the bands that gave me hope that I could be part of this beast called rock and roll. People come up to me and say, [Patti Smith’s debut album] Horses changed their life. We keep on passing things along in the same way: you hear a piece of music from a certain era and you start translating it in your head and it becomes the music of the next era. I believe we’re all part of this birth and rebirth process that is the music. I like when things move forward. I’m not one to say, “I wish music was like it was 40 years ago.” I don’t. We did live through a golden era of the music we appreciate and lump under the definition of rock and roll, but really, music has to exist in the present tense. Now, we’re hearing the music of the 21st century find its way of expressing itself. It’s not going to be guitar-centric and it might not even be wed to a three-minute pop song. And, hey, that’s progress. It was interesting to me, while doing the book, to see that rock and roll has gone through its many evolutions and now it’s going to take its place with all the other classic musics of humankind, whether it’s madrigals of the Renaissance, or Dixieland jazz or bebop. It’s great that we have all these musical explorations. New categories are being invented all the time and that’s where the future reveals itself.

Listen to “Crazy Like a Fox,” a single released by Kaye in 1966 under the name Link Cromwell

Do you see a line connecting the various scenes you wrote about?

They all have in common a sense of yearning and wanting to claim their own space, to begin again. And it’s interesting that each of them has their arc, where it coalesces out of mood, the personality of the city, the reaction against what came before. These ideas start coming together, almost like cosmic dust starts to form a planet. And then, all of a sudden there’s a realization that something different is happening, and that something different starts moving out into the world at large where, in a certain way, it becomes simplified and defined and loses some nuances and then becomes its own cliché or stereotype. Then it’s time for something new. Once things get hardened into a style, it’s time to start breaking it down and start over.

The younger generations now have a different way of absorbing new music than those who came up in the classic rock era. They don’t go to a record store and come home with a 45 or an LP; they just go to Spotify or YouTube and click on a song and it plays. Has something been lost?

I like the availability, but I also like the thrill of the hunt, personally. I like the artifact. I like to hold the record in my hand. I like to go to a record fair looking for something, because when I’m looking for it, I’ll find a lot of adjacent other stuff that I perhaps have never heard of before; there are millions of records. People love to make music. Everyone says, oh my gosh, there are 60,000 songs a day uploaded to Spotify, but stuff rises to the top. And there are probably fewer gatekeepers to let you know what you should be listening to. But I like that sense of serendipity where you start looking for something and then you find that, two hours later, tracking it through this rabbit hole or another, you wind up in a place that you’ve never been. When I go to a record fair looking for 45s, I’ve heard of maybe 10 percent of what’s there.

That’s a good segue into the Nuggets compilation that you put together for Elektra Records in 1972. It might have just started out as a collection of oddball songs, mostly by one-hit wonders, but over a period of several years, it actually kickstarted a whole new musical movement. There were hundreds of similar compilations that came in its wake: more Nuggets volumes, plus Pebbles, Back From the Grave and so on. And then a slew of new bands formed that revived that sound and took it to new places. Did you have any notion that this album would open up a wide-scale resurgence of ’60s garage-rock or psychedelia?

I didn’t really have that much of an idea. If you listen to the original Nuggets, it’s stylistically all over the place. I was working from a perspective of four or five years [after those singles were released], and the intuition that something interesting happened there. I had a chance to do it, thanks to [Elektra Records president] Jac Holzman. So in a weird way, I had the pick of the litter, but it was kind of feeling around in the dark. Jac and I were finding those lost records; he wanted to preserve it for history. Over the two years it took to come up with the Nuggets album, it’s still all over the place, really. Sagittarius’ “My World Fell Down” is an orchestral masterpiece, a lot different than the Seeds [“Pushin’ Too Hard”]. In a weird way, Nuggets exemplifies how the scene developed, in the sense that you have a lot of different things happening. Tom Verlaine [of the ’70s New York band Television] once said about the CBGB scene that every band was a different idea. That’s true. Television was certainly not punk except maybe a certain attitude. The Patti Smith Group was not really punk, but we had a certain sense of we’re going to forge our own path. With Nuggets, after a few years, certain aspects of what I put together rose to the surface and became garage rock.

Listen to two tracks that were included on Nuggets

The original subtitle of Nuggets doesn’t say punk or garage though. It very specifically says, “Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965–1968.” How would you delineate that era?

It’s the first psychedelic era because the second one would be around the San Francisco time when all of a sudden everything became more expansive and more elastic and a little more hallucinogenic. Nuggets really caught an interim period, a transitional period, and that to me is when the interesting things happen. Again, I was just feeling my way. If I would have thought that we would be talking about Nuggets 50 years in the future, I would have certainly fucked it up because I would have been very self-conscious about the definition of what I was doing.

The world wasn’t ready to hear those mid-’60s songs again in 1972 because the rock audience had moved on. The album never charted and it had a delayed reaction. I didn’t know anyone who bought Nuggets in 1972, myself included, but all of my friends had it by the end of that decade.

Sometimes you need a little historical perspective. It was a little early for people to realize [what it was about], but I’m sure it would have been figured out in the same way rockabilly was later figured out. I just happened to have an opportunity to gather these records together, and then, that’s when the fun begins, because once you get something figured out, then the archeologists come into play and find those incredibly scarce records. My kind of Nuggets are not that defined. Patti and I have tried to resist that [classification of music] too—we want the freedom to be able to be all musics, to be unpredictable, to go outside our own borders and parameters and explore. In a certain way, that’s why we have been able to be together for half a century. Nuggets created a lot of psychic space for experimentation and the bands that listened to it and found their sensibility within it took from that sense of possibility.

Watch Lenny Kaye and the Patti Smith band cover a medley of “nuggets” of the ’60s

You end Lightning Striking in 1991 with Seattle’s grunge music scene. Did the regional rock music phenomenon cease to exist then, and if so, why?

We’re talking pre-internet, and an incubation period that any scene needs when it’s really off the beaten path. It’s also about the people there, what they call for, what their social framework is, what the town is like, how it influences the style of dress that comes through, what the audience responds to. Is that possible when everybody is linked and as soon as you do a piece of music you throw it up on the internet? The CBGB bands clustered around a really downtrodden bar on the Bowery’s skid row and had a year and a half to make mistakes on stage, trade band members, play for each other, develop a communal consciousness of what they were doing, even though they expressed it very differently. Rock and roll is approaching 70 years, so obviously there comes a time when it enters into its golden years. I don’t mourn it. I’m ready for something new, but I also know that within that span of rock and roll’s lifetime, you can spend forever finding those things that need discovery and expansiveness.

Related: When Bruce Springsteen joined Patti Smith onstage

How did being in a popular band affect your perspective of what you’re writing about?

It helps me understand how the music is made from inside itself. I always felt, as a rock writer, aside from the fact that I have a certain obsessive penchant for research, that I knew what it was like to be within a band. My career as a musician started in the mid-’60s at the same time I began writing. I could position myself, when I listened to a record, within the band, on the side of the drummer, somewhere near the bass player or the rhythm guitarist, and how music sounded to the musicians. I understand the narrative arc of a guitar solo, and that really helps inform what I do on the printed page. But it’s nice to be out in the audience too. I know what it’s like when I’m at a metal concert and I push my way to the fifth row and lose myself in the high frequencies of sound that are pouring off the stage. I think it’s an important way to appreciate music. It’s the experience of music that I take to heart. I understand when somebody comes up to me and says, “That was really great. I was so moved.” I understand that I’m that person, that I’m sometimes on the stage. I’m moved by the band locking into a certain way and accelerating, by being that person who’s enchanted by the music, unlocking that emotion. I’m not a trained musician. I don’t read music. But I can feel music. If I can convert that feeling into a sentence I’m writing, then I’ve unraveled my own complex personality in terms of being a musician and a writer and, of course, a fan.

You just talked about going to metal shows, yet your previous book, You Call It Madness, was about crooners of the 1930s, people like Russ Columbo and Bing Crosby? That’s quite a range of interests.

We contain multitudes, as I like to say. What I mostly listen to now is country music from the ’50s and ’60s. I like all music; I always like to find new music to get into. I’m not sure if there’s any left. I probably have a Latin music moment ahead of me. I love reggae, and once it was revealed to me, thanks to The Harder They Come soundtrack and Bob Marley, I started going to record stores in Brooklyn and asking them to play me everything on the shelf and I took the ones that I liked and not the generic ones. About a year and a half ago, I was at a local antique auction in Pennsylvania, and they had four crates of 2000-era, 12-inch techno. I thought, well, it’s interesting. So I bought them, it cost me about 10 bucks a crate, and over the last year and a half, I’ve been going through them and I’ll put on a couple, dance to it, see if anything is happening besides somebody just turning on a drum machine. Out of those four crates, I have maybe two-thirds of a crate filled with techno nuggets. Any genre you pick, you can find the great records. I might not be interested in accumulating an entire collection, but I like having the ones that I like. There’s so much different music. But I’m not interested in the third iteration of a sound—I’m interested in the original. If you can tell the source, then maybe the music has figured itself out too well—you’re in the era of interpretation as opposed to innovation, which is what I think we’re in with rock and roll. It’s like the blues. There’ll be incredible blues players coming along, but you’re not going to do anything different with the blues, or bebop or free jazz, or even rockabilly. Brian Setzer is an awesome guitar player who took it to a whole other level with his orchestra, but still it’s interpreted. It’s not that moment where somebody invents something. What I’ve always been into is what is the new thing? I know that music sounds a lot different than it did 30 years ago, and that’s good. There’s a certain sense that rock and roll has become classic, and if it’s classic, that means it’s great. But the 21st century has to have its own music. Otherwise we’re stuck.

Watch: The MC5 figure heavily in the Detroit chapter of Lightning Striking

A touchy question: Is rock and roll finally dead?

It will never be dead, because its building blocks are there; it’s there to be appreciated in the same way that the George Jones record I bought from 1954 the other day is not dead, because it spoke to me. Is rock and roll the adventurous new kid on the block? I don’t think so. But it’s there to be discovered in the same way that, if you put on a Beethoven symphony, you will have worlds of emotion revealed, in the same way that, when you listen to Jimi Hendrix, you understand that these are the building blocks of what might be the future. I don’t think any musics die; it just happens to be when you discover it and you open your ears to it. That doesn’t mean that that’s it, that there’s going to be no more music in the world. I’m all about a phrase of Patti’s that always comes back to me: Progress isn’t the future. It’s keeping up with the present. That is what I try to do.

One last question. It’s been a decade since the last Patti Smith album. Is there ever going to be a new one?

I don’t know. We’re not really working on a new record. Patti is involved with her writing projects. I’m involved with my writing projects. We’re out there touring as much as we can in these very strange times. But the fact is that we have 12 albums under our belt. There’s a lot of songs in the world, and too often bands just keep on doing what they do. If we’re going to do another record, we want it to have a meaning that transcends what we’ve done before. We have a couple of pieces of music we’re playing around with, but at this point, we want it to be future-oriented as opposed to reiterating what we’ve done in the past. I never say never. Certainly, it’s wonderful playing our body of work to people who seem to be getting younger as we’re getting older. It’s wonderful to look out at our audience and see how many younger people are deriving inspiration from who we are and what we hope to be. Patti is an amazing performer. I’ve had the privilege of standing stage left of her for all these many years. I’ve never, ever seen her sing a false note or go through the motions at a show. She is always completely present, trying to make each night special in its own way. That is our responsibility to our audience and one we definitely try to fulfill any time we’re out there doing what we do. We have been privileged to be given this opportunity. It’s a great honor to be on that stage and to play for people and to not let them down.

Watch the Patti Smith group perform their hit cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Because the Night” in 1978

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024