Sometime around 1969, record producer Norman Dayron—fresh from producing the multi-generational Fathers & Sons album by Muddy Waters and his younger disciples—ran into Eric Clapton, who may have been backstage at an Al Kooper/Mike Bloomfield show, or perhaps it was a Blind Faith concert. No one seems to remember for sure. In either event, Dayron seized the opportunity to ask Clapton if he’d like to record an album with master bluesman Howlin’ Wolf.

Sometime around 1969, record producer Norman Dayron—fresh from producing the multi-generational Fathers & Sons album by Muddy Waters and his younger disciples—ran into Eric Clapton, who may have been backstage at an Al Kooper/Mike Bloomfield show, or perhaps it was a Blind Faith concert. No one seems to remember for sure. In either event, Dayron seized the opportunity to ask Clapton if he’d like to record an album with master bluesman Howlin’ Wolf.

Would he?!! Would he ever! But was this a legitimate proposition? After confirming that Dayron was a staff producer at Chess Records, and that the offer was indeed legit, arrangements were made by Chess Records. Howlin’ Wolf—born Chester Burnett on June 10, 1910, in White Station, Miss.—would come to London. Clapton was over-the-moon excited, yet agreed under one condition: that Howlin’ Wolf’s longtime guitarist, Hubert Sumlin, be involved as well. There was some initial balking at Chess regarding the expense of flying two players from Chicago O’Hare to Heathrow. But eventually they agreed.

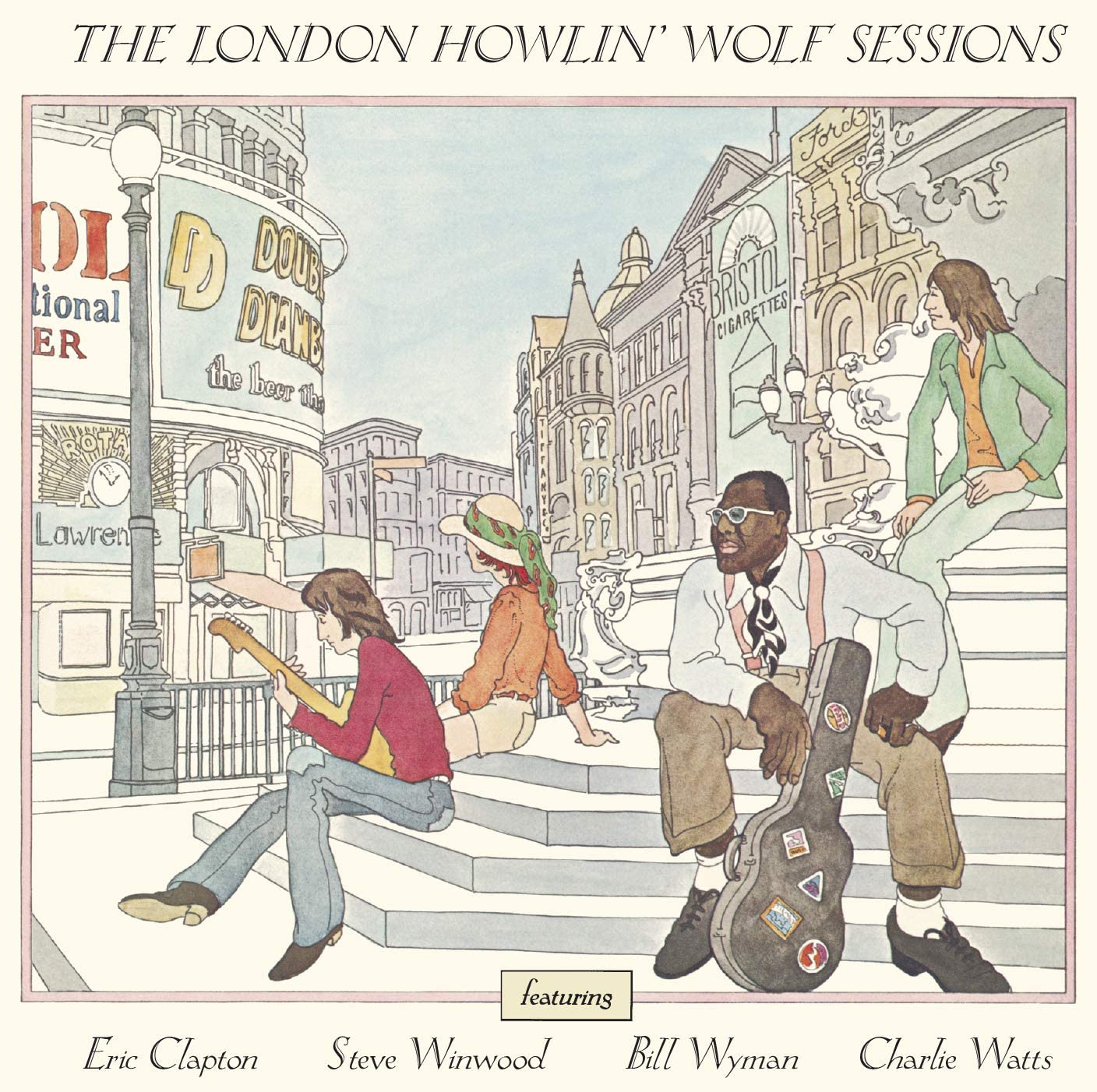

From May 2-10, 1970, at London’s Olympic Studios—home of sessions for the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and David Bowie, among others—the house was rockin’ with Howlin’ Wolf and British rock royalty. Clapton was enlisted to play lead guitar on each of the 20-some songs, some being alternate takes) with Sumlin on rhythm guitar. Thankfully, Clapton yielded to Sumlin in establishing the songs’ grooves, although Sumlin’s rhythm work dominates “Do the Do.” And on “The Red Rooster,” Clapton nods not only to Sumlin, who played on Wolf’s 1961 original, but also to Keith Richards and Mick Taylor’s guitar moods.

On most tracks, the Rolling Stones’ rhythm section was enlisted: Bill Wyman, bass; and Charlie Watts, drums, with Klaus Voormann on bass for one song (five if one counts the bonus tracks that saw the light of day on the 2003 expanded reissue), and Ringo Starr on drums on one track from the original album (plus three reissue bonus tracks). When Voormann laid down the song-defining bass riff on “I Ain’t Superstitious,” Wyman played the cowbell. And yet another Rolling Stone (albeit not an official band member), Ian Stewart, played piano on “Rockin’ Daddy.”

Curiously, Howlin’ Wolf, who played both rhythm guitar and his signature low blows on the harmonica, didn’t get to play much of his trademark harmonica on the London Sessions. Instead, Dayron brought in 21-year-old University of Chicago student Jeffrey Carp, a prodigy who’d played with Waters on Fathers & Sons (a conceptual precursor to Chess’ London Sessions series), John Lee Hooker, Earl Hooker, Sam Lay, Chuck Berry, Tracy Nelson and even the Soulful Strings.

The presence of Carp enabled harmonica, heard between vocal phrasing on vintage Wolf recordings, to play straight through the verses. A reviewer from Canada’s Edmonton Journal noted that “the late Jeffrey Carp provided fireballs of musical punctuation via his blistering shots on harmonica.” Producer Dayron, in a 1976 San Francisco Examiner interview, called him “the most important talent I’ve ever worked with.” He was a bona fide ensemble player (listen to his synergistic playing on Bo Weevil Jackson’s composition “Poor Boy”), and some felt he’d exceeded his mentor Little Walter. Clearly, he was going places. Sadly Carp lived to be only 24 years old, drowning two years after the London Sessions while on vacation in the Caribbean on New Years Day 1973.

Make no mistake: The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions was not recorded entirely at London’s Olympic Studios. Back in Chicago, the sessions were augmented at Chess’ Ter-Mar Studios with longtime Chicago blues pianist Lafayette Leake on piano, and nimble jazz guitarist Phil Upchurch on bass. A horn section containing Jordan Sandke, trumpet; Dennis Lansing, tenor saxophone; and Joe Miller, baritone saxophone—part of the band called the 43rd Street Snipers—was added. And while most listeners probably assumed he’d been part of the London basic track sessions, British keyboard legend Steve Winwood (Traffic, Blind Faith) overdubbed piano and organ on five tracks while on tour in the U.S. He was the only artist who recorded during the Chicago sessions to have his name emblazoned on the album’s front panel.

Though one could refer to Clapton’s classic guitar work and Winwood’s keyboard work as “stylized” (think “After Midnight” or “Arc of a Diver”), they were mindful to serve the star and his songs. At certain points, it’s impossible to distinguish between Clapton and Sumlin (apart from Clapton playing most of the solos) and between Winwood and first-generation Chicago blues pianist Leake. John Simon, a popular producer in the late ’60s (Leonard Cohen, The Band, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Janis Joplin) takes a turn on piano on ‘Who’s Been Talkin’.”

Though one could refer to Clapton’s classic guitar work and Winwood’s keyboard work as “stylized” (think “After Midnight” or “Arc of a Diver”), they were mindful to serve the star and his songs. At certain points, it’s impossible to distinguish between Clapton and Sumlin (apart from Clapton playing most of the solos) and between Winwood and first-generation Chicago blues pianist Leake. John Simon, a popular producer in the late ’60s (Leonard Cohen, The Band, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Janis Joplin) takes a turn on piano on ‘Who’s Been Talkin’.”

As for the Wolf, he could do no wrong. The year 1970 found him in excellent voice, spirits and energy, able to moan, growl, snarl, roar and bellow as he’d done since his earliest Sun Studio sessions in 1951. Were there London Sessions songs on which he excelled more than others? Absolutely. “Worried About My Baby,” on which Wolf played his own harmonica, comes to mind. (There are two additional outtake versions of “Worried About My Baby” on the expanded reissue, the most intriguing of which features Wolf, Clapton and Wyman, with no drummer.)

And the groove of Willie Dixon’s “Wang Dang Doodle” and, on the expanded reissue, “Killing Floor,” come to mind. The Wolf saved some of his best howlin’ for the Willie Dixon-penned classic, which closes the original LP, released in August 1971.

Wolf plays his own guitar on “I Want to Have a Word With You,” presumably a then-new song as it doesn’t turn up on his previous discographies, his vocals marked by an uncommonly spatial delivery. He’s backed on that one by Voormann and Starr.

Marshall Chess, son of Chess Records founder Leonard Chess and the vintage blues label’s ambassador to the rock generation, and later president of Rolling Stones Records, recalls, “I was transitioning from leaving Chess to the Rolling Stones. I was in London and stopped by the studio. I remember Wolf sitting in a chair with a sour look on his face. I went over to him and asked, ‘What’s up?’ He told me that he wasn’t feeling too well and would be glad to get back home. He said the sessions were going well and that Eric Clapton could sure play the guitar. He also told me Eric had given him a real nice fishing rod.

“I was glad to see Hubert there and had a good social time hanging around the studio,” Chess added. “I also remember hearing the album after all the overdubs were completed Chicago and liking what I heard.”

Related: When the Stones introduced Howlin’ Wolf to American rock fans

3 Comments

I found a CD version of this somewhere in the 90’s, and got blown away – those were days when the internet was still crawling, so I had no idea this existed. Of course I bought it right away, and I remember listening to it and thinking how cool those legends felt by playing with someone that was also a legend even by their standards. It’s impossible to listen to Wang Dang Doodle without hearing everyone playing with an ear to ear smile on their faces during that session.

Wolf famously said of the outing, something like ‘Those English cats sure are gentlemen, and they sure do love the blues. Can’t play ‘em very well, but sure do love ‘em.’

Em pensar que lá em casa tinha este disco, e ouvíamos as vezes entre tantos outros bons, e minha mãe inocentemente jogou todos fora!!!!