By spring of 1973, the Southern rock movement was solidly entrenched. The genre’s earliest catalyst, Phil Walden’s Macon, Ga.-based Capricorn Records, was one of the earliest indie label success stories of rock’s album era.

By spring of 1973, the Southern rock movement was solidly entrenched. The genre’s earliest catalyst, Phil Walden’s Macon, Ga.-based Capricorn Records, was one of the earliest indie label success stories of rock’s album era.

The Allman Brothers Band had released not only their breakthrough two-LP At Fillmore East (1971) but the comparably song-oriented Eat a Peach (1972)—their last recording with brother Duane Allman—with Brothers and Sisters (August 1973) not far behind. Wet Willie had released two albums as well, their breakthrough with the single “Keep On Smilin’” still a year away. Only White Witch, Capricorn Records’ odd band out (its image more glitter-rock than Southern rock), failed to gain traction.

Meanwhile, working for MCA, as opposed to Capricorn, Lynyrd Skynyrd had released its Al Kooper-produced debut, Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd. That LP contained “Gimme Three Steps,” but, far more importantly, a nine-minute album closer that would become a Southern rock anthem: “Free Bird.”

With most of the action shakin’ out of Georgia and Florida, it was time for adjacent South Carolina to get into the game. Enter The Marshall Tucker Band from Spartanburg, S.C. Spartanburg is “quiet, rural, mellow,” Jerry Eubanks, the band’s flutist, saxophonist and keyboardist explained to me at a show at Northern Illinois University’s Evans Fieldhouse in DeKalb, Ill., in December 1974. “The people [in Spartanburg] don’t know a hell of a lot about rock ’n’ roll, but they don’t bother you. The climate is temperate. The mountains don’t let it get too hot or too old.”

Eubanks was also quick to explain that no one in the band was named Marshall Tucker. Rather, the name emanated from an inscription on a key that opened the door the group’s old practice headquarters. The band later found that the warehouse it was renting for rehearsal space had been previously rented by a blind piano tuner. The members practiced in that space five nights a week and all held day jobs as well. Occasionally, they’d gig locally. Once they felt their repertoire had congealed sufficiently, they contacted Phil Walden at Macon’s Capricorn complex.

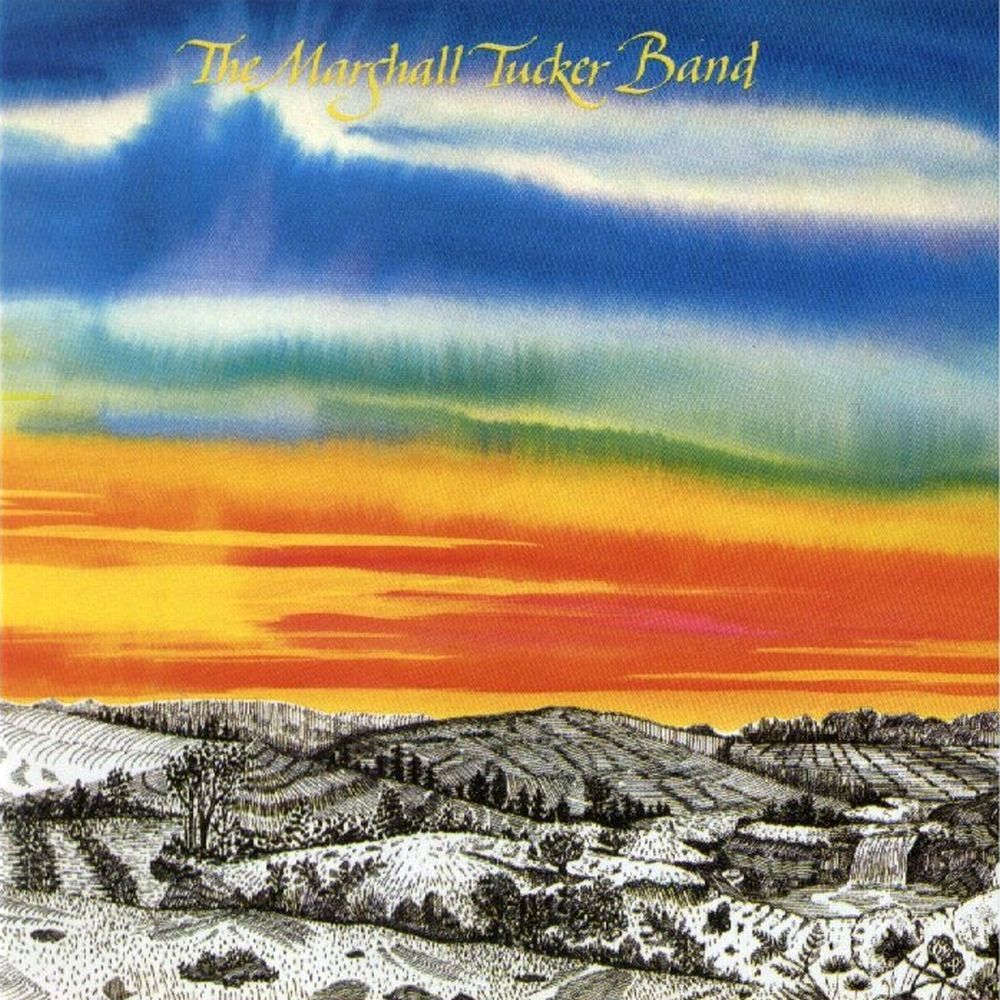

In April 1973, the Marshall Tucker Band released their debut album for Capricorn, produced by Paul Hornsby, whose credits also included Gregg Allman, Elvin Bishop, the Charlie Daniels Band, Captain Beyond, Livingston Taylor and Grinderswitch. Hornsby had played with Duane and Gregg Allman in two precursors to the Allman Brothers, the Hour Glass and the Allman Joys.

Related: 11 great Southern rock albums

The eponymous Marshall Tucker Band album rolled off the presses in 1973 and spawned two hits, “Take the Highway,” with its itch to ramble, and the lover’s lament “Can’t You See.” (Forty-nine years and several new technologies later, it’s fair to say “Can’t You See” was the far bigger hit of the two, registering 174 million Spotify spins compared with a non-unrespectable eight million spins for “Take the Highway.” “Can’t You See” was reissued and reworked as a single four years later in 1977, and was spotlighted in the 2017 Tonya Harding biopic I, Tonya.)

“We may be getting big,” Eubanks explained in 1974, “but we ain’t never aimed at making a hit. Our single, ‘Take the Highway,’ was just the LP track chopped up. None of our songs are conceived as singles. We didn’t want to think of entering that side of the market until our albums proved us. If it happens now, I wouldn’t object. If a band starts off with a hit, it sticks with them. People start coming to the concerts to hear the single and you get a different kind of crowd.”

That said, it’s difficult to imagine the band, which has lasted half a century and still records and tours, would object to having a hit record nowadays. (As it turns out, they had a few more in the rock idiom before pivoting to mainstream country in later decades. Or, more to the point, mainstream country had by then come around to what the Tucker Band always did.)

“I guess you could say at one time, the rest of the nation thought we were hicks,” Eubanks said. “Now they’re coming around and seeing a lot of their Northern bands ain’t so hot. Otis Redding, he was Southern music in the truest sense. I can’t recall a time when there wasn’t Southern music.”

The debut album, like the spectrum of Southern rock itself, showed more diversity than early Allman and Skynyrd fans gave it credit for. While “Ramblin’” is a Southern boogie number that would have been at home on an early Allmans album, “Losing You” expanded the scope of instrumentation with its intricate weave of mandolin, pedal steel and piano.

The folky “Ab’s Song,” which for what it’s worth boasts the album’s third greatest streaming popularity in the decades that have ensued, is a dying young man’s last request: “If I die at 23, would you bury me in the sunshine? Please let me know that you’re still mine. And when the grass grows over me, let me know you still love me.”

The album’s odd song out, however, is a live version of the 1935 blues classic “Every Day I Have the Blues,” originated by Aaron “Pinetop” Sparks and Milton Sparks, and covered post-World War II by Memphis Slim and B.B King. The 12-minute blues jam, kicking off with a Toy Caldwell guitar solo, could have been a track on the Allmans’ At Fillmore East.

Jumping ahead to the present day, the Marshall Tucker band’s discography has grown to 22 studio albums and seven live albums, with 12 compilations albums as well. When Capricorn faced bankruptcy in the late ’70s, the band segued to Warner Bros. In 1980, co-founder and bassist Tommy Caldwell (Toy’s brother) suffered a massive head trauma in an auto accident and passed away shortly thereafter. By 1984, the only remaining original members were Eubanks and lead vocalist Doug Gray. By 1993, the band had formally embraced Nashville and vice versa— Garth Brooks contributed a song (“Walk Outside the Lines”), calling the opportunity to write for them a “milestone” in his own stratospheric career. The band scored five charting country hits (it had charted country three times in the late ’70s). Eventually, Eubanks left the fold (he later operated a business called Flatwoods Soaps in Spartanburg), and Firefall’s David Muse joined the band.

Related: Classic rock albums of 1973

“We’re a band of serious musicians,” Eubanks concluded as we spoke in 1974, “so we have little to do with AM radio. We don’t feel restricted. We’ll do it as long as it remains interesting and nonrestrictive. It could be three weeks. It could be 10 years.”

Try 50 years! And no end in sight!

The Marshall Tucker Band’s discography—including their great debut—is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Bonus Video: Two young guys react to hearing “Can’t You See” for the first time.

4 Comments

Excellent article about an excellent band on an excellent website. I love the bios for the writers. It’s nice to know we are receiving amazing insight from people who actually lived and breathed in the music industry. Keep UP the great work.

PS – You have me curious about which classic rock songs top the Spotify charts. Maybe an article or two could be mined from them. Thanks again for all of your hard work.

The live version of “Every Day I Have the Blues” is only available on the CD reissue and is not included on the original vinyl release.

You’re right. Everyday I Have The Blues was on Where We All Belong. I still have my old vinyl copy which listed Toy singing and playing lead on a live version of Can’t You See, which was not on that album but would appear on Searchin’ For A Rainbow. That being said, this was a great article.

Saw them at Shea’s Buffalo in 1975. Winters Brothers opened. Two phenomenal bands that night. The current version is painful to see in concert. Please stop touring.