Back in 2008 and 2014, this author, who has a long history with the sole surviving member of the Monkees, interviewed Mickey Dolenz, born March 8, 1945. Those conversations were never before published until Best Classic Bands did so in 2022. Here are highlights from both sessions…

Best Classic Bands: You were in show business as a preteen, in the TV program Circus Boy [1956-57], long before The Monkees. Is it true that you played guitar on a Circus Boy press tour?

Micky Dolenz: I did. I played “Purple People Eater” by Sheb Wooley. I did Billy Williams’ “Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter” [a Fats Waller tune] and David Seville’s “The Witch Doctor,” songs I was hearing on radio stations in Los Angeles, on my guitar. I must have started guitar when I was eight or nine, classical guitar and then folk music. I would play when kids came over for a party or I would go to a party. I wasn’t [Andres] Segovia but I could do [the folk song] “Tom Dooley.”

My first public appearance was in 1957, opening for Bimbo the elephant at Kennywood Park in Pittsburgh—two songs with a local band. They backed me on “Witch Doctor” and “Purple People Eater,” and then the elephant came on. We went to places like Pittsburgh and Chicago, then New York’s Grand Central Station.

Do you remember your audition for The Monkees?

I remember my audition for The Monkees very well. I had an agent, Ted Wilk, who said, “You have an audition.” I went down. I think the reason I remember it well is because it was in the same building, and possibly the same office, where I auditioned in the ’50s for Circus Boy. It was one of the ugliest offices (laughs). It looked like a brick wall. Obviously, I got a call-back. The next one was probably the interview, answering questions. The next one I’m pretty sure was the musical one. They had a back lot with guitars and drums, keyboards. It was kind of like a jam, an open mike. That’s where I played “Johnny B. Goode” on the guitar. And the last one that I remember, the screen test with scripts and scenes.

I think by then there might have been eight candidates left. The only one I remember was Davy [Jones]. I don’t remember Mike. That’s because Davy and I just had a lot in common. We had both been in television, and he had been on stage. Maybe they paired us up. I remember one of the major scenes I did with Davy. We came up with a bit of shtick where he and I were wearing hats. Bill Chadwick, Michael [Nesmith] and Peter [Tork] were there. Bill later worked with us as a songwriter and on the series. I recall Davy and I had a lot to talk about concerning TV, film and stage. And that was it. We had a jam.

I went back to school at Los Angeles Trade-Technical College to study architecture. I never was formally trained in acting. I was doing day jobs on TV shows. I was going to school. I wanted to be an architect. I went to Valley Junior College. If the architect thing didn’t work out, I was gonna fall back on show business.

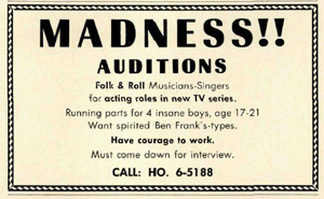

I knew The Monkees was going to be a pilot, and I knew that pilots mostly do not get sold. I saw the ad [for actors] in Variety. It wasn’t in the music papers. They were going for four kids who just jumped off the screen, four characters that were charismatic and different. If I was producing, that is what I would have done. Not, “I gotta have a keyboard player.” It was a TV show, as I have often said, about a band. It wasn’t a band. And the producers knew that. They had great visions of what it could be. The music was not at the top of the list of their priorities. It had to be there, and we had to be comfortable around music, but it was heavily weighted toward the improvisation.

What was it like the first time you, Davy, Mike and Peter were together?

The first time the four of us were together as the Monkees was at the wardrobe fitting, I recall, at the middle of the lot:

“This is Mike, Peter, Davy.”

“I’m Micky. Nice to meet you.”

“Great. Congratulations. You guys are The Monkees.”

But I didn’t get enormously invested in the whole thing. I knew it was a pilot. It was late November 1965. I was still going to school when we did the pilot. I was kind of encouraged to be kind of goofy and improvise and be unusual.

History has shown the group had chemistry.

It obviously clicked and it had chemistry. It’s almost the absence of any conflict that probably was more to the point. Even in the pilot and early episodes it was very clear to us when we got a script who was the right person to say that line. We would often say, “That is a line for Peter, not Davy.” On some rewrites we would just swap lines. The characterizations were like the Marx Brothers, similar in many ways in terms of personalities to the Beatles even—things that happen in a group who are like-minded and have the same taste in music. They have the same dynamic, which is wonderful for music.

The singularity of musical vision would never work on television if all of them were like Groucho and all of them were doing Groucho. It doesn’t work. You have to have the distinction.

I did the pilot and went home. I remember hanging out at Mike’s place. He had a drum kit in his apartment. He gave me a drum lesson before the series started shooting [in January 1966]. It moved fast. But for two months we were hanging out. The series got picked up. That is when I quit school.

Related: Here we come… The Monkees’ incredible first year

You had an innate sense of rhythm.

In the pilot, I didn’t know I was going to be the drummer. I remember being told, “You are the drummer.” (laughs). They had a lot of guitar players. Looking back, of course, the idea was to have Davy be the front man, Mike on guitar. I remember immediately starting drum lessons. Later on, I watched [drummer] Earl Palmer and picked up tips from him.

Watch Episode 19 of The Monkees

You used your own name in the series.

I often wonder what would have happened to us, and what would have happened to the whole brand and the marketing, plus us as individuals, if we would have had character names. That is probably the biggest unknown question about The Monkees. Would it have been as successful? More successful? Less successful? After The Monkees, would we have been able to move on and do other things as actors and entertainers, having played the part? Would the whole [controversy] initially about us not playing instruments been as big a deal with the fans? We will never know.

After the show took off, when did you start making public appearances?

That was Christmas of 1966, two months after the show was on the air. That was the first time I realized, “Holy shit! Something is going on here.” I had only been at the studio and at home. I had no idea what was happening. There was a big “Last Train to Clarksville” promotion done in conjunction with local radio station KHJ. I remember the train. We were flown in by helicopters, landed on the beach. Some idiot said, “You guys are gonna have to play on the way back.” But how do you set up a band in a train? When the train started, the cymbals were flying all over the place, and crazy amps. It must have been godawful. We played “Clarksville” and two other songs, maybe a couple of Mike’s tunes. No one figured out that the train rocked back and forth. How would they have even gotten power to the amps?

When was the first time you heard the group on the radio?

That I do remember, because I had never heard myself on the radio. I was living with Davy and we were coming back from the set. It had been announced on KHJ that it would be Monkees Day or something like that, so we were listening. It started playing as we pulled up to the house. We looked at each other: “Wow!” We were at [co-producer] Bert Schneider’s house when we saw the actual series debut. I believe Natalie Wood was there. I think he was dating her at the time, if I’m not mistaken. Bob Rafelson [the other co-producer] and his wife Toby were there. I don’t think I brought anybody. Every few weeks I would watch an episode.

The Monkees had an enduring influence.

Dr. Timothy Leary said in his book, The Politics of Ecstasy, “The Monkees brought long hair into the living room.” And I think that may be the legacy. It made it OK to be a hippie, have long hair, and wear bell bottoms. It did not mean you were a criminal, a dope-smoking fiend commie pervert. At the time the only time you saw people with long hair on television, they were being arrested or treated as second-class citizens.

Let’s not forget that The Monkees was a TV show about an imaginary band that lived in this beach house and had these imaginary adventures. It was theater. It was probably the closest thing to musical theater on television. It was about this band that wanted to be famous, wanted to be the Beatles, and it represented in that sense all those garage bands around the country and the world. On The Monkees show, the Monkees were never famous. It was all about the struggle for success that made it so endearing I think to the public, anyway.

I remember Ringo once, years later, telling me how the music business had changed so much. “You know, all you had to do in the old days was show up with your drums and you were in the band.” (laughs). And that’s true.

In the documentary film Monterey Pop, shot at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, we see a brief glimpse of you in the audience. You’re wearing a huge Native American headdress. Peter was also there.

I very nearly never went to Monterey. To me, Monterey was a fun weekend. At the time it wasn’t this huge, cultural watershed event. But I don’t think it was to anybody. It was this festival that John Phillips, Lou Adler and some people tried to put together. There had been other festivals, love-ins and be-in things. Monterey ’67 was another one in the series to some degree. But everyone was talking about Monterey. “It’s gonna be so cool.” But I was working the night before and probably working the night after. The night before I was at a recording session with the Monkees doing the vocal on “Words” and the next morning I went up to Monterey with Peter. Peter introduced a couple of the acts there.

I remember people talking about Monterey happening, but it was almost a spur-of-the-moment thing. I had a leather suit made with a Nehru collar but it had bone buttons and bell bottom pants, and it had a loin cloth over the bell bottom pants (laughs). And, naturally, I wore Fairchild moccasins, too. I was in a conversation with Gene Ashman, the wardrobe coordinator for The Monkees TV show, and he knew I had Indian heritage; it was common knowledge, I’m half, Italian, half Indian and half Irish. Anyway, I asked him for an Indian headdress. And I still have it to this day. I schlepped it on the plane, and probably wore it on the flight (laughs). In Monterey, people were in color.

What was the musical highlight of Monterey for you?

Ravi Shankar. But to be honest, it wasn’t just him, it was the tabla player, Alla Rakha. Of course, being into drumming, those rhythms I was very unfamiliar with, as were most people of those Indian rhythms. So it wasn’t just Ravi, it was the whole thing, along with Kamala [Chakravarty, the other musician accompanying Shankar]. I remember being astounded by Alla and those patterns he played, because I was heavy into playing drums at that time, for the television show, and studying drums. It just totally blew me away. They made a big impression on me.

At the time of the Monterey 1967 event it was all one sort of zeitgeist and the community at that time was quite small and local; it was only really California and New York that had any real hippie community to speak of. It was the counterculture, and there were only a couple places in the country you could get away with it without being arrested. I wasn’t as deeply invested into that counterculture as others might have been. At the time, there were some people who got what the Monkees were all about, like Frank Zappa, my friend Harry Nilsson, John Lennon.

You gave Jimi Hendrix a big career boost by having him open some 1967 tour dates of the Monkees.

We were looking for a great opening act at the time as we had a tour planned. I had seen Jimi Hendrix earlier as a backup guitarist for John Hammond Jr. in New York. He was a sideman in 1966. Someone told me I had to go to this club to see this guitarist who played with his teeth. I didn’t know his name. John Hammond was pretty incredible. Then, at Monterey, I’m sitting and Jimi, Noel [Redding] and Mitch [Mitchell] come on stage. Jimi had gone to England, and Chas Chandler [of the Animals] put a band together for him, the Jimi Hendrix Experience. By the way, does that mean they were manufactured? Half of Jimi Hendrix’s set at Monterey was cover versions, too.

Watch Micky perform Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” in 2019

Jimi walks out on stage, and I recognize him. “Hey! That’s the guy who plays guitar with his teeth.” I suggested him for our tour because he was very theatrical. And, the Monkees were theater. I saw Jimi at Monterey, told our producers, who got in touch with Chas Chandler and then Jimi’s booking agent. Everyone thought it was a great idea. I fell in with Jimi. [After the Monterey set], we all sat for hours, until the morning. I later crashed out at the Carmel Inn. Everyone was hungry and thirsty, and maybe it was the Boy Scout in me, but I wanted to contribute to the vibe, so I went out of the tent and somehow found a case of oranges. I lugged this entire case of oranges back to the camp, the tent, and started giving out oranges, like I was “Little Johnny Orange Seed.” I think I might have also heard at the time that oranges or orange juice were helpful after an indulgence of chemicals.

Watch Micky Dolenz perform “Goin’ Down,” one of his most dynamic numbers with the Monkees

Related: When the Monkees sang with Johnny Cash

The Monkees’ recordings are available here.

4 Comments

“Day Dream Believer” is one of my favorite all time tunes! The Monkees music I heard when I was serving in the jungles of Vietnam, was good for my morale!

Welcome home brother.

USMC I Corps

I’ve seen Micky perform a number of times and, unfortunately, feel a great ambivalence about him, in that, while I feel he’s never really gotten his due as one of the greatest pop singers of all time, and his same Monkees fame that made him famous in the first place, may well have obscured his actual talent. But when seeing him perform live, it’s like he, himself, does not take his own talent seriously enough, and always resorts to the same sort of sophomoric humor that he did with the Monkees, as if that’s what fans are going to see him for. Personally, I find it annoying and off-putting — here’s a guy who sang recorded versions of some of the greatest pop songs of all time, with his incredible voice, but, for some reason, still feels the need to be funny while performing these songs. Micky, you deserve so much better a legacy, but you’re not helping yourself out much either.

I’ve seen Mickey Dolenz live, too. He has a GREAT pop music voice, one that has been sadly overlooked and underappreciated. I doubt that he’ll ever get his due, but he certainly deserves to get it. He’s that good. Really.