The first thing you hear is kick drum and a splatter of fatback bass, followed by the distorted psychedelic guitar phrasing of Pete Cosey, a member of Miles Davis’ ensembles between 1973-75, frequently compared to Jimi Hendrix in his day.

The first thing you hear is kick drum and a splatter of fatback bass, followed by the distorted psychedelic guitar phrasing of Pete Cosey, a member of Miles Davis’ ensembles between 1973-75, frequently compared to Jimi Hendrix in his day.

And then a very familiar voice—that of Muddy Waters, father of Chicago blues—singing the Willie Dixon classic “I Just Want to Make Love to You.” As always, he sang it likes he meant every word.

So imagine a suburban pre-teen at home, taking this in on the then-new frontier of “underground” FM radio in 1968. “That was Muddy Waters from his new Electric Mud album with ‘I Just Want to Make Love to You,’” came the laid-back DJ’s back announcement.

And while the album would find itself the object of critical scorn—not an authentic blues album, a sellout and worse—it served its purpose right there and then: introducing a new generation to blues.

Indeed, Muddy Waters, the Rolling Fork, Miss., native who began his career in 1942 with Library of Congress field recordings captured in his house at Mississippi’s Stovall Plantation, had come full circle.

Quoted in author Robert Gordon’s biography of Muddy Waters, Can’t Be Satisfied, album producer Marshall Chess explained the concept: “I came up with the idea of Electric Mud to help Muddy make money. It wasn’t to bastardize the blues. It was like a painting, and Muddy was going to be in the painting. It wasn’t to change his sound, it was a way to get it to that market.”

Suffice to say the mojo worked on this listener. Within months of hearing it on FM radio, I was out buying older Muddy Waters albums and every Chess/Checker LP I could find. With Electric Mud as my gateway drug to blues, I was soon buying albums on labels like Delmark, Arhoolie, Yazoo, Document, Prestige, BluesWay and Spivey.

For the album’s May 1968 sessions, Marshall Chess brought his present-day “A” team to the label’s Ter-Mar Studios (Marshall was the “Mar” in the studio’s name). He shared co-producer credit with Charles Stepney, a songwriter, producer and multi-instrumentalist whose credits included the Dells, Ramsey Lewis, Rotary Connection and Earth, Wind & Fire; and also tenor saxophonist Gene “Daddy G” Barge, whose horn blurts on Electric Mud are few and restrained. Also enlisted: Jazz guitarist Phil Upchurch joining the aforementioned Pete Cosey and third guitarist Roland Faulkner; Louis Satterfield wielding firebrand electric bass; and Morris Jennings, drums. Many had recently recorded with Marshall Chess’ other recent ensemble project, Rotary Connection.

Marshall, 26 at the time he conceptualized Electric Mud, had grown up with the blues, of course. His father was Chess Records founder Leonard Chess, né Lejzor Szmuel Czyż, who along with Marshall’s uncle, Phil Chess, had theretofore supervised nearly every Muddy Waters session for Chess Records and its predecessor, Aristocrat Records, since Muddy joined the labels in 1948.

Waters’ first recordings were the downhome “Can’t Be Satisfied” and “Feel Like Going Home.” As the ’50s unfolded, the singer would meet former prizefighter, bassist, producer and (most importantly) songwriter Willie Dixon. Dixon would bestow upon him some of his best songs ever, steering Muddy toward a new urban beat: “Hoochie Coochie Man,” “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “Mannish Boy” and “I’m Ready,” to name a few. By the time he played a concert set, there wasn’t a soul in the house who wasn’t convinced of his prodigious virility. As he sang in “Hoochie Coochie Man,” Muddy was “gonna make pretty women jump and shout. And then the world wanna know what this all about.”

Many of the songs were Waters classics recast in a milieu of psychedelia: “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “Hoochie Coochie Man,” “I’m A Man,” “She’s All Right” and “Same Thing.”

But there were a few unexpected choices. After years of the Rolling Stones covering Muddy Waters songs, Muddy endeavored the Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” changing up the phrasing and making it his own. Sidney Barnes and Robert Thurston’s composition “Herbert Harper’s Free Press” had never been recorded before. But when Jimi Hendrix heard it on Electric Mud, he reportedly listened to it for inspiration before every concert he played. And Waters’ common-law stepson, Charles Edward Williams, contributed “Tom Cat.” The album had only eight songs, clocking in at an average of 4.5 minutes per song.

The album, released on Oct. 5, 1968, did receive a modicum of FM rock airplay, and did help connect the dots for a lot of late ’60s rock fans. There’s that name again, many must have thought when they saw the recurrent Willie Dixon songwriting credit, straight out of their Cream, Led Zeppelin and Steppenwolf albums. Thus in many respects, the album accomplished its mission statement.

The critics weren’t so sure – and their disdain continues to this day. In the Nov. 9, 1968, edition of Rolling Stone, respected critic, label owner and archivist Pete Welding opined that “Electric Mud does great disservice to one of the blues’ most important innovators, and prostitutes the contemporary styles to which his pioneering efforts have led.” All Music Guide’s Bruce Eder, years after the release, wrote: “This album marks what could probably be considered the nadir of Muddy Waters’ career, although at the time it did sell somewhere between 200,000 and 250,000 copies, a lot for Waters in those days.” New York blues blogger J Blake adroitly observed: “The band does not seem to be playing with Muddy. There is no cohesion between the vocals and the band’s playing, as if Muddy’s voice was sampled from previous recordings and just laid over the album’s hard driving, frantic and very noisy backing tracks, resulting in a sound not unlike the one created with the contemporary sampling methods used in hip-hop.”

According to author Nadine Cahodes in her book about Chess Records titled Spinning Blues into Gold: The Chess Brothers and the Legendary Chess Records, session guitarist Cosey believed the criticism was misplaced. From a musician’s perspective he thought the ideas were good ones and that Stepney’s arrangements were “brilliant…[taking] the music in a totally different direction. Cosey would ‘bet the ranch,’ he added, that none of the album’s critics could play the parts that had been written to back up Waters [on Electric Mud].”

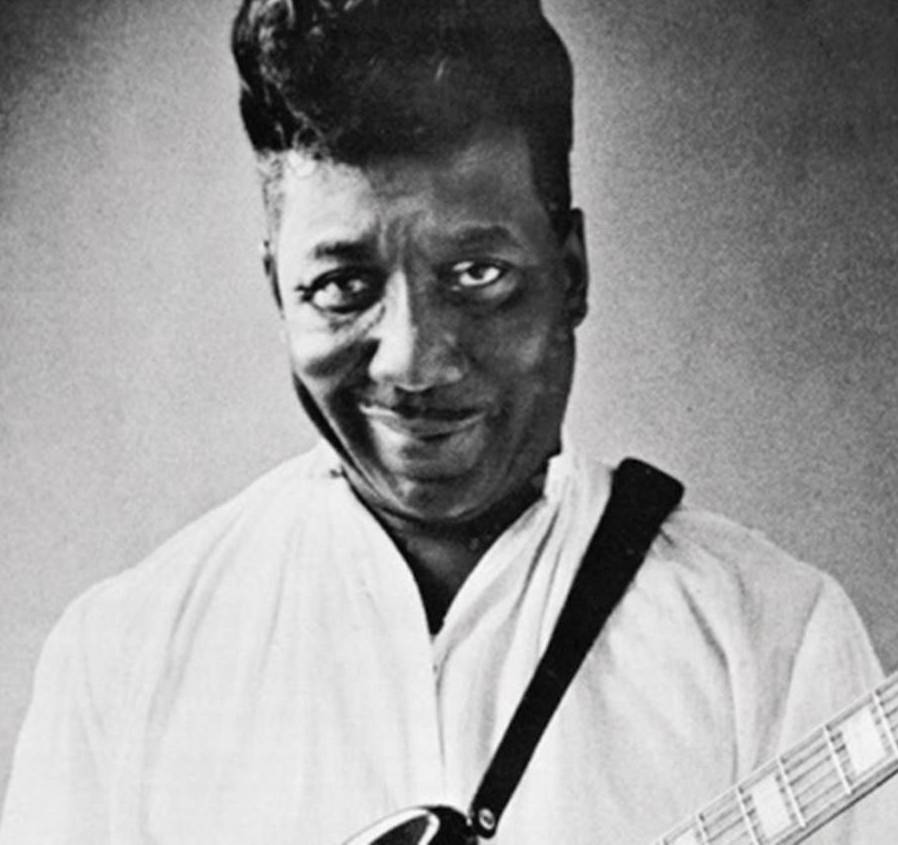

One would be remiss not to mention the cover, inside and out. The front of the album, in the tradition of the Beatles’ “White Album” and the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet, was white with plain black letters reading “ELECTRIC MUD.” But inside the gatefold was the visual pay dirt: Waters in a long white tunic, with a processed ’do (his trip to the hair salon is documented elsewhere in the packaging), with one of the coolest electric guitars you’ll ever see.

His half-smirk assures listeners he was in on the joke—and that was important.

The album appeared on Marshall Chess’ imprint at Chess Records, Cadet/Concept. But Chess itself would soon go through some major changes. Following the 1969 passing of Leonard Chess, the Chess label was sold (foolishly then and in retrospect) to GRT (General Recorded Tape), where it was merged with short-lived Janus Records. Marshall stayed on as a consultant. And, after one more electric Waters album (After the Rain, in many ways superior to Electric Mud), he found ways to keep Waters relevant to the rock audience with a slightly more authentic bent: 1969’s Fathers & Sons paired “fathers” Muddy Waters and Otis Spann with “sons” Paul Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield, Duck Dunn and Sam Lay, recorded live in concert. 1972’s The London Muddy Waters Sessions juxtaposed Waters, harmonica player Carey Bell and longtime drummer Sammy Lawhorn alongside British rockers Steve Winwood, Rick Grech, Rory Gallagher and Mitch Mitchell, reprised with the 1974 sequel London Revisited.

Marshall did, however, attempt the Electric Mud template with Howlin’ Wolf. It didn’t take quite as well. The album, formally titled The Howlin’ Wolf Album, was noted for is cover copy: “This is Howlin’ Wolf’s new album. He doesn’t like it. He didn’t like his electric guitar at first either.” That was to say the least. “Man, it’s dogshit,” Wolf was quoted as saying in Rolling Stone. In retrospect, Marshall Chess said, “I used negativity in the title, and it was a big lesson: You can’t say on the cover that the artist didn’t like the album. It didn’t really sell that well. But it was just an attempt. They were just experiments.”

Besides, neither Wolf nor Waters were strangers to electric guitars. Both were, after all, patriarchs of the plugged-in, bar-weaned Chicago blues sound. They just hadn’t gone whole-hog psychedelic prior to their coaxing by Marshall Chess.

Marshall himself, of course, soon left Chess under GRT, perhaps feeling he was underutilized or disrespected, and joined his friends the Rolling Stones, who he’d first met at Chess studio in 1964-65, as founding president of the band’s Rolling Stones Records.

Muddy Waters had some of his best career years ahead of Electric Mud. Following the two London albums (the first winning a Grammy Award in 1973), he released They Call Me Muddy Waters and The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album, both Grammy winners also. He left Chess (or, perhaps more correctly, Chess left him) in the later ’70s, upon which he released three Grammy-winning LPs for Johnny Winter’s CBS-distributed Blue Sky Records label: Hard Again, I’m Ready and Muddy “Mississippi” Waters Live. He is also a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Blues Hall of Fame inductee, and multi-Blues Music Award winner. His longtime home at 4339 S. Lake Park Ave. on Chicago’s South Side has received Chicago landmark designation and awaits conversion to a museum, a major boon to the up-and-coming Kenwood neighborhood.

Related: Waters was one of the performers at the legendary “The Last Waltz” concert

Waters died from heart failure at age 70, on April 30, 1983, at his newer home in suburban Westmont, Ill. Sons Larry “Mud” Morganfield and Big Bill Morganfield sail on with the family musical tradition, though a third performing son, Joseph “Mojo” Morganfield, died in 2020.

Waters’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

1 Comment

Excellent article. This was a favorite back when. I never understood the crappy reviews either. I saw it as Muddy cashing in on the prevalent tastes of the day that were taking inspiration from the earlier blues guys. He did it better I thought.