Who woulda thought? Once a singer whose emphasis focused on pure pop of a decidedly whimsical variety, Harry Nilsson’s image became at least temporarily tainted after palling around with a bad boy Beatle. It’s not that Nilsson hadn’t shifted direction before. Ever since establishing himself with a pair of bona fide hits—“Everybody’s Talkin’” from the film Midnight Cowboy and his chart-topping remake of Badfinger’s “Without You”—his career had seemed like it was on an upward roll.

Who woulda thought? Once a singer whose emphasis focused on pure pop of a decidedly whimsical variety, Harry Nilsson’s image became at least temporarily tainted after palling around with a bad boy Beatle. It’s not that Nilsson hadn’t shifted direction before. Ever since establishing himself with a pair of bona fide hits—“Everybody’s Talkin’” from the film Midnight Cowboy and his chart-topping remake of Badfinger’s “Without You”—his career had seemed like it was on an upward roll.

Following 1970’s Nilsson Sings Newman—a timely tribute to then-emerging singer/songwriter Randy Newman—and his contributions to the soundtrack for The Point!, a cartoon short that attracted a cult adult following, he reemerged with a series of albums that brought him a new, hipper following. Nilsson Schmilsson and Son of Schmilsson showed considerable promise and gained airplay on FM radio, before being derailed by the decidedly schmaltzy A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night and the ill-advised attempt to reboot the horror movie genre with Ringo Starr’s film vehicle, Son of Dracula.

By 1974, Nilsson’s once-promising career was floundering and it would clearly take something significant to get him back on track. That need seemed to be filled when he began hanging with members of the new Hollywood rat pack, a group of boozing buddies affectionately referred to as the Hollywood Vampires and whose membership included John Lennon, Keith Moon, Ringo Starr, Alice Cooper and other assorted members of L.A.’s rock star elite. Lennon was a particularly strong presence; having temporarily parted with wife Yoko Ono and transplanting himself to the Left Coast, he began acting out his frustrations with new pal Nilsson in tow. The two did have a history; once asked to name their favorite American singer, the Beatles had given Nilsson that nod.

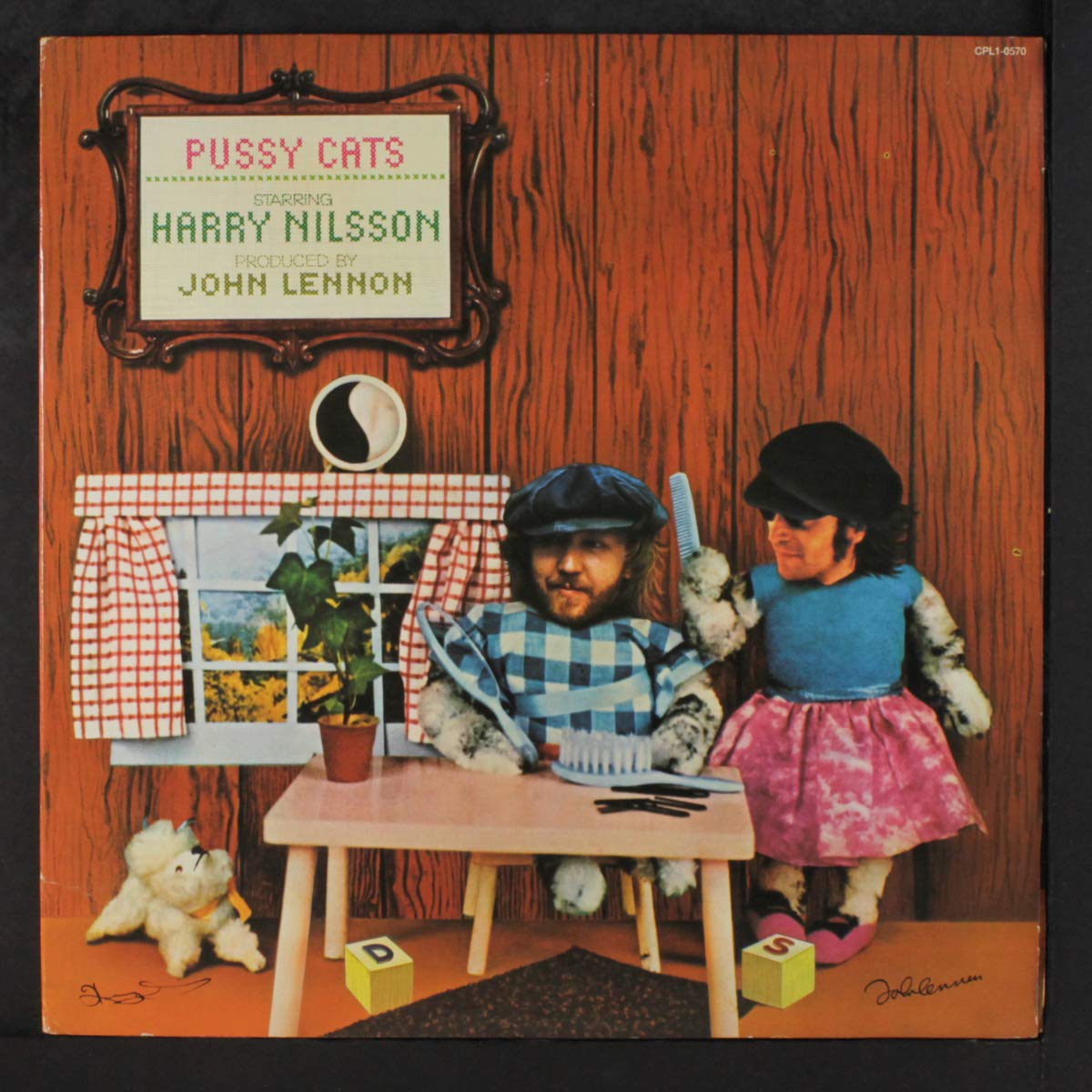

It felt only fitting, then, that Lennon would find a fit as the producer of Nilsson’s next album, originally titled Strange Pussies in a nod to their outlaw image, but later changed to Pussy Cats at the insistence of Nilsson’s record label, RCA, for its August 19, 1974 release. Not surprisingly, the sessions attracted an eager cast of characters, among them guitarists Danny Kortchmar and Jesse Ed Davis, pedal steel player Sneaky Pete Kleinow, longtime Beatles associate Klaus Voormann on bass, Stones sax man Bobby Keys, drummers Starr, Moon and Jim Keltner, and any number of other studio insiders as well. The second night of recording brought two other big-name visitors, Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder, and a belated bootleg of mostly inconsequential jamming later emerged, aptly titled A Toot and a Snore in ’74.

Nilsson and company barely concealed the presence of drink and drugs—the album cover alludes to the substance abuse by picturing children’s blocks showing the letters D and S precisely situated on either side of a rug, the word “drugs” being the operative implication. Somehow though, the formal recording sessions coalesced into a decent album, one that was half covers, half original songs, including one mellow ditty co-composed by Lennon and Nilsson in tandem, “Mucho Mungo/Mt. Elga,” a song with a mellow drift that prefigures Lennon’s “# 9 Dream,” which would appear on Lennon’s Walls and Bridges album later that same year.

While some of the Nilsson originals showed his promise as a newly liberated songwriter, particularly a cluster of songs on side one—“Don’t Forget Me,” “All My Life” and “Old Forgotten Soldier”—as always, his true talent was realized in the efforts that found him interpreting the work of others. That’s especially true of his stirring version of the Jimmy Cliff classic “Many Rivers to Cross,” which finds him wailing with unfettered emotion and intensity.

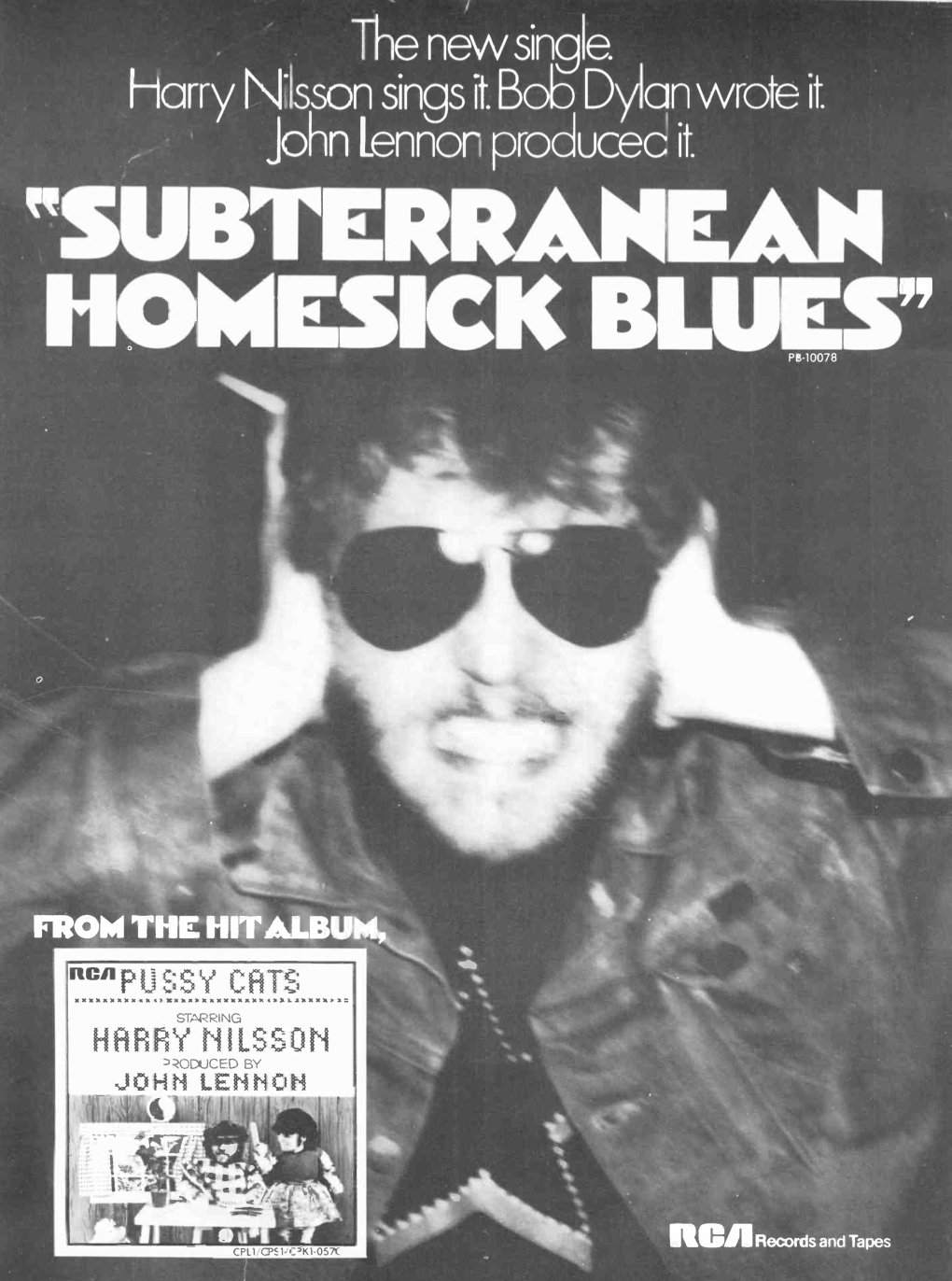

So, too, Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” becomes a wild, unhinged ramble of a recording. To the contrary, the classic “Save the Last Dance for Me” is shared with a sentiment and sincerity that’s clearly illuminated throughout. Here again, it’s the romantic Nilsson at his best.

What’s not immediately apparent is that the singer had ruptured his vocal cords, a fact he kept secret from Lennon so as not to force the project off the rails. The strain is evident on the pair of oldies the pair opted to include toward the end of the album, the raucous “Loop De Loop” and “Rock Around the Clock,” the latter of which finds Ringo, Moon and Keltner bashing away in tandem with ricochet rhythms.

Ultimately, Pussy Cats marks the final peak in Nilsson’s career. He continued making records, but never again would he make an album that boasted such notoriety. When he died of heart failure on January 15, 1994, at the age of 52, his magnificent voice was sadly stilled forever.

Bonus Video: Watch a mini-documentary on Pussy Cats, posted by the Harry Nilsson Archive

Related: Our Album Rewind of Nilsson Schmilsson

2 Comments

PUSSY CATS is definitely a chronicle of two great artists of the 1960s in a very bad way. Nilsson was killing his career and Lennon was trying to crawl his way back to mediocre. On the surface, you want sooooo much for the album to work! But it only does in a couple of spots. Lennon had just helped Harry garner a bigger contract with RCA, but ol’ Harry just didn’t have the good and / or new material to back it up. Also, looking back on his seven years on RCA, his two biggest hits (“Everybody’s Talking” and “Without Her”) were covers. Also, John was trying to live down his topical songwriter / revolutionary, social commentator era. This incredible “lost weekend” was very close to claiming them both.

Back in late 1993, I did some work on a couple songs for a self-financed Ringo album that was never finished or released. The first night of the sessions, Harry Nilsson (and his sober coach) stopped by the studio to say hi. I wasn’t involved beyond that first night, but it was really special to see them together.