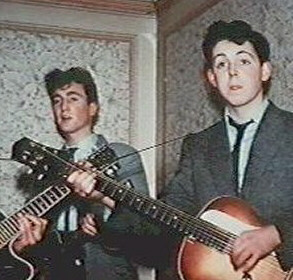

The Beatles aren’t thought of as a guitar band the way that the Rolling Stones are, but if you love guitar, there’s that much more to love about the Beatles.

The Beatles aren’t thought of as a guitar band the way that the Rolling Stones are, but if you love guitar, there’s that much more to love about the Beatles.

George Harrison was usually the man responsible, especially in the early days, for the guitar solos in Beatles songs. He was no innovator, but a player easy to adore on account of his tone and tendency to restate what were always formidable melodies—thanks to John Lennon and Paul McCartney—in his solos.

Those melodies gave the Beatles a formidable leg up as a band, and Harrison the guitarist understood what a good thing was and utilized it. He was capable of cutting lose, but that was generally reserved for BBC sessions (or the second solo in “Long Tall Sally” from The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl), which had an experimental quality, albeit a controlled one. The days of Revolver and Sgt. Pepper were still some ways off, even if the BBC did serve as a kind of underrated radiophonic workshop for the band.

By his own admission, Harrison didn’t practice much, adding that he would have been much better if he did. Props for candor, anyway. One doesn’t imagine that John Lennon practiced much either, but his guitar style, with its aggressive corrosiveness, didn’t lend itself to discipline, paradoxically enough.

Lennon could, as he said, make the guitar scream and howl, which he was sometimes called on to do as a soloist—with his own “You Can’t Do That” being a prime example—but he was also a surprisingly tasteful, even dexterous player when need be. One only has to think of the demanding triplets throughout most of “All My Loving,” or the nimble, light-heeled touch in evidence on both “Honey Pie” and “Get Back.”

Lennon could, as he said, make the guitar scream and howl, which he was sometimes called on to do as a soloist—with his own “You Can’t Do That” being a prime example—but he was also a surprisingly tasteful, even dexterous player when need be. One only has to think of the demanding triplets throughout most of “All My Loving,” or the nimble, light-heeled touch in evidence on both “Honey Pie” and “Get Back.”

The longer one listens to the Beatles, the more one appreciates McCartney, who apparently could have done anything he wished musically between the years of 1963 and 1969.

When we use the word “consummate” to describe someone—as in, “He was a consummate pro” or a “consummate pianist”—the implication is that they’re not dynamic. They epitomize stability, and stability doesn’t suggest, or allow for, daring. It’s something that can be counted on, not something that reaches skyward itself.

McCartney, though, was both consummate and daring, the way that Mozart was, or Charlie Parker. It may be his most salient musical quality when he was at his best. He didn’t play much lead guitar with the Beatles, but when he did, it was always dynamic—startling, even.

McCartney has five key moments as a Beatles lead guitar player, with one of them somewhat muted by dint of having two other lead guitar players join him, which is what happens with the long medley of Abbey Road. We get nine guitar solos, with McCartney, Harrison and Lennon, in that order, taking three guitar solos each, the solos having a length of about two bars.

Harrison is at his virtuosic best, especially on his third solo. One may be taken aback that he could play at this level. He’s come a long way from the laughable attempt at a guitar break on “One After 909” in March 1963 that caused Lennon to audibly sneer, “What kind of solo was that?”

Lennon’s solos on the medley represent the primal power of rock and roll—why the Beatles got into the game in the first place. His playing carries that theme, sonically embodying its heart and soul and as such represents his all-encompassing moment—as human, rebel, Beatle, rocker—as a guitar player.

Related: “I’m Down,” the overlooked Beatles song

McCartney sets up his bandmates. He’s the distributor, the point guard. Miles Davis was a master of not so much laying out, but almost laying out while also playing at a high level that seemed to make it easier for others to be at their best.

That’s the McCartney of the long medley. He doesn’t need the splashy moment. Harrison and Lennon are better suited to do their respective things here, in this context, with everything that implies and conveys. Someone had to take charge of the guitar section of the medley, and kick it off, and that somebody was McCartney.

“Taxman” was the George Harrison song that sufficiently impressed Lennon and McCartney, and producer George Martin, that it was placed at the start of Revolver. Beginning and ending Beatles records was a big deal. Here was Harrison’s breakthrough moment in the band, but it’s McCartney who plays the solo on the song. Harrison wouldn’t have been able to. Not this solo.

What ends up being overlooked is Harrison’s own impressive playing on the track, those raga-style lines—with an aspect of rhythm and blues and sci-fi sheen—toward the end. He made his guitar mark on his key number. The McCartney solo, though, is that rare Beatles guitar blast that could feature on a record by Jimi Hendrix or Cream, without producing incredulity. It’s the guitar god solo, but with class and economy—and taste.

Harrison probably wasn’t threatened—his focus was his song. The Beatles always knew how good they were, and they certainly knew it in what turned out to be their mid-career prime. McCartney’s intensity dazzles. This is a solo, but one might better think of it as a barrage that also binds the song together. Its immediacy stuns and the solo is over, it seems, just as it has started searing you.

Dave Davies’ solo on “You Really Got Me” is similar, in that it’s impossible to sense that it’s coming, never mind how it will go once it arrives. But if ever a guitar solo felt like an electric current jolting through a listener’s body, this would be it. Quite the lead guitar debut for someone in a band that had been making records for more than three years.

Was McCartney just a natural? Did he practice regularly? There’s a difference between writing a song on a guitar—which takes minimal technique (Sam Cooke, for example, wrote his songs on guitar, and there aren’t Sam Cooke guitar solos that we celebrate; there aren’t any)—and playing a solo to marvel at. But few musicians have ever been as deft as Paul McCartney. You never think there’s something he couldn’t do or play.

He’s the lead guitarist on the next year’s opening title track to Sgt. Pepper, but not on the reprise of the song, and his stinging lines, with their traces of vibrato, set a key tone for the album.

There will be Edwardian brass band pomp and whimsy, yes, but don’t forget, those lines seem to say, this is a rock and roll band. Sgt. Pepper wasn’t going to be a music hall record. At times on the LP, the Beatles rocked as hard as ever, and McCartney’s guitar had a lot to do with that.

Lennon’s “Good Morning Good Morning” is a song that needs a little help from his bandmates, including his best friend in Paul McCartney. The number is akin to a driving television commercial that also happens to be overloaded, staccato rock music.

Watch McCartney explain how he wrote “Blackbird”

McCartney’s solo is once again a heated affair. It’s a thermometer-melter. He plays as fast as the likes of an Alvin Lee in Ten Years After. Perhaps this was how McCartney felt he had to play in order to solo well, and looked at this as the one technique in the tool bag. But more likely, speed was the approach that best served these two songs, and so he played what he played, just as he would have played something else for something else.

Less well-known is his guitar contribution to his own “Back in the U.S.S.R.” Harrison plays the solo in which he leans on his old technique of repeating the melody, but the Harrison of 1968 isn’t the Harrison of that “One After 909” session of five years back.

He gets a power chord tone without employing power chords, and appears to be so pleased with what he’s just put on tape—as well as he should have been—that the close of the guitar solo features a sort of sonic signature, a distorted little sign-off, as if to say, “courtesy of George Harrison.”

McCartney comes in later, on the song’s close, with controlled tendrils of tart sustain that suggest what Harrison has already played, but as if they’re unpacking that solo and extending the materials of it. Fanning out the guitar lines, as it were, while also suggesting the engine effects of a jet. McCartney the songwriter is serving the song, which is also what the best guitarists do, even if there’s a high razzle-dazzle quotient to their playing.

Who would better understand that union than Paul McCartney, the man who excelled at both? We don’t have a lot of chances to turn up the volume and relish his guitar playing in the Beatles, but nor do we lack for them. It really is as if there’s a consummate and dynamic blend that both thrills and is exactly as how it ought to be.

Watch Paul play “Yesterday” solo on acoustic guitar in 1965

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

2 Comments

I once read that Eric Clapton claimed that George Harrison was the best slide guitarist he’d ever seen. While George was a great player and definitely underrated, EC did play with Duane Allman who arguably was one of the greatest in music history.

George not innovative?

stopped reading