In the autumn of 1972, buoyed by the success of his first post-Simon and Garfunkel album and its hit singles “Mother and Child Reunion” and “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard,” Paul Simon was ready to record the followup LP with his longtime, trusted producer-engineer Roy Halee. They’d already co-produced a track called “Tenderness,” recorded in New York City the week after Simon’s wife Peggy gave birth to their son Harper. Simon had his pick of New York session musicians, and snagged a horn arrangement from New Orleans legend Allen Toussaint. He also brought in the rootsy Dixie Hummingbirds to sing backup. Simon was primed to extend his interest in gospel, jazz, reggae, Latin rhythms, R&B and doo-wop to the rest of the LP.

In the autumn of 1972, buoyed by the success of his first post-Simon and Garfunkel album and its hit singles “Mother and Child Reunion” and “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard,” Paul Simon was ready to record the followup LP with his longtime, trusted producer-engineer Roy Halee. They’d already co-produced a track called “Tenderness,” recorded in New York City the week after Simon’s wife Peggy gave birth to their son Harper. Simon had his pick of New York session musicians, and snagged a horn arrangement from New Orleans legend Allen Toussaint. He also brought in the rootsy Dixie Hummingbirds to sing backup. Simon was primed to extend his interest in gospel, jazz, reggae, Latin rhythms, R&B and doo-wop to the rest of the LP.

But Halee was bogged down finishing another project, which miffed Simon no end, especially when he discovered the roadblock was his old friend and nemesis Art Garfunkel. “I was caught in the middle,” Halee told Robert Hilburn, Simon’s biographer. “If I had known Art’s album [Angel Clare] would take so long, I would never have agreed to do it. Paul was the one I wanted to work with. But now that I had started the album, I felt obligated.” [Our interview with Simon biographer Robert Hilburn.]

Simon pivoted to another expert engineer-turned-producer, Phil Ramone, who had quite a range himself, having worked with Peter, Paul & Mary, Quincy Jones, The Band, Dusty Springfield, Frank Sinatra and many others, winning Grammys for engineering the Brazilian-American jazz fusion of Getz/Gilberto in 1965 and the Broadway original cast recording of Burt Bacharach’s Promises, Promises in 1970.

Simon had been fired up by hearing the Staple Singers’ hit “I’ll Take You There” in spring 1972, and wanted to record with the backing musicians on the record, who he assumed were African-Americans based in Memphis, where the Staples’ label Stax famously operated. Instead, he was directed by Stax’s Al Bell to Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in rural Alabama, where the young white guys initially dubbed “the Swampers” (and now known under the more professional name the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section) were located. They were the players Simon wanted.

Keyboardist Barry Beckett, drummer Roger Hawkins, bassist David Hood and guitarists Pete Carr and Jimmy Johnson had worked with Aretha Franklin, Percy Sledge, Wilson Pickett, the Rolling Stones and a zillion others, and were known as quick studies, adaptable to any situation. When Simon wanted the studio booked for a few days to record a new tune called “Take Me to the Mardi Gras,” the guys told him they were used to knocking out any song in an hour. They were being modest—they nailed the joyous, light reggae backing track in 30 minutes, after listening to the Jamaican instrumental “Liquidator” just before tape rolled. “Paul was flabbergasted that it took us so little time to get the groove and the attitude of the song,” said Beckett later. “Paul goes for attitude, then groove, then color, and we caught all those ingredients very fast.” Ramone and Simon later laid in Dixieland horns and a gorgeous falsetto vocal by the Reverend Claude T. Jeter to the track, adding further to the unique hybrid.

Simon is often rightly lauded for his lyrics, but throughout his career he’s been much more likely to begin his composing with a melodic or rhythmic idea and fill in the words later. Another new song Simon brought to Muscle Shoals had begun with a melody fragment joined to the temporary phrase “going home.” The search for a better rhythmic equivalent, something that might avoid clichés, led him to “Kodachrome,” the brand name for Eastman Kodak’s color film. The images of childhood and high school suggested by “going home” turned into a poetic meditation on how our memories “color” the past, and how technology “hypes” it: “Kodachrome/They give us those nice bright colors/They give us the greens of summers/Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day.”

“Kodachrome,” which the Rhythm Section banged out right after “Take Me to the Mardi Gras,” begins with one of Simon’s most sardonic openings (“When I think back on all the crap I learned in high school/It’s a wonder I can think at all”) and depends once again on the lightness of Beckett’s electric piano, Hawkins’ reggae-ish drumming and the interplay of Simon’s acoustic guitar with Johnson and Carr.

Simon was so thrilled with the Rhythm Section’s contributions he gave them co-producer credit on those two plus “St. Judy’s Comet,” “One Man’s Ceiling is Another Man’s Floor” and “Loves Me Like a Rock,” all of which were recorded when Simon returned to Muscle Shoals in March 1973.

He also recorded part of “Was a Sunny Day” there, but without the Swampers playing (he brought some of the New York crew down South). Supervising overdubs at Columbia and A&R Studios in New York, Simon and Ramone meticulously added small but crucial touches to the basic tracks. All said, nearly 30 musicians participated, including bassist Bob Cranshaw, drummer Grady Tate, keyboardist Bob James and singing sisters Maggie and Terre Roche (who’d been taught songwriting by Simon at an NYU class he gave).

“St. Judy’s Comet” is a lullaby for Harper (there’s no comet involved, Simon getting the title from the drummer in Clifton Chenier’s zydeco band, Robert St. Judy), and shows Simon’s deft way of winding in humor even inside heartbreakingly tender tunes (“I’m going to sing it three times more/I’m going to stay ’til your resistance is overcome/’Cause if I can’t sing my boy to sleep/Well it makes your famous daddy look so dumb”).

“One Man’s Ceiling is Another Man’s Floor” begins with an arresting descending piano line from Beckett, then turns into a bluesy, funky groove, Simon having a delightful time declaiming his lyrics in a variety of voices. By the time it hits the all-out bridge (“There’s an alley in the back of my building/Where some people congregate in shame”) the song’s melodic roots in “St. James Infirmary” are clear.

“Learn How to Fall,” recorded at another storied R&B landmark, Malaco Recording Studios in Jackson, Miss., is a mesh of jazz and folk, with a lovely, loose Simon vocal and terrific fills from guitarist Jerry Pucket and organist Carson Witsett.

“Something So Right,” recorded in New York before the Muscle Shoals sessions, began life as “Let Me Live In Your City” (Simon had performed it on Dick Cavett’s TV show in July ’72), but on There Goes Rhymin’ Simon it focuses completely on Simon’s relationship with his wife. It contains a raw series of confessions, every bit as powerful as Simon’s autobiographical lyrics to “I Am a Rock,” “Kathy’s Song” or “Homeward Bound.” He sings, “I was in crazy motion/’Til you calmed me down,” “When something goes right/It’s likely to lose me/It’s apt to confuse me/It’s such an unusual sight/I can’t get used to something so right” and “I’ve got a wall around me/That you can’t even see.” Simon commissioned Quincy Jones for the string arrangement, and it somehow echoes and cushions the sweet ambivalence of the lyrics.

In an album full of treasures, “American Tune” still stands out, and has only gained resonance since Simon wrote the lyrics as “my Nixon sore-loser song,” setting them to a melody line from a chorale in “St. Matthew Passion” by J.S. Bach. Ironically recorded in Morgan Studios in London, it features Simon on guitar with James, Cranshaw and Tate in support, with a string arrangement by Del Newman. Looking back in 2017, Simon told Hilburn, “I was writing about what I felt was the end of sixties beliefs—that idealism…I’m sure I was aware of the irony of being so over the top to call a song ‘America’—as if you could wrap up the country in a song—so to call the new song a ‘tune’ rather than a ‘song’ has the opposite effect.” The song is just as spiritual as “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” but is more stark and modest in approach.

The lyrics are brutally honest in the verses (“I don’t know a soul who’s not been battered/I don’t have a friend who feels at ease”) and surreal during the bridge (“And I dreamed I was flying/And high above my eyes could clearly see/The Statue of Liberty sailing away to sea”). By the end, his delicately controlled vocal plainly states his simple role as a songwriter among fellow citizens: “We come in the age’s most uncertain hour/And sing an American tune/But it’s alright, it’s all right/We can’t be forever blessed/Still, tomorrow’s going to be another working day/And I’m trying to get some rest.” Like many Paul Simon originals, the song has no repeating chorus.

The lyrics are brutally honest in the verses (“I don’t know a soul who’s not been battered/I don’t have a friend who feels at ease”) and surreal during the bridge (“And I dreamed I was flying/And high above my eyes could clearly see/The Statue of Liberty sailing away to sea”). By the end, his delicately controlled vocal plainly states his simple role as a songwriter among fellow citizens: “We come in the age’s most uncertain hour/And sing an American tune/But it’s alright, it’s all right/We can’t be forever blessed/Still, tomorrow’s going to be another working day/And I’m trying to get some rest.” Like many Paul Simon originals, the song has no repeating chorus.

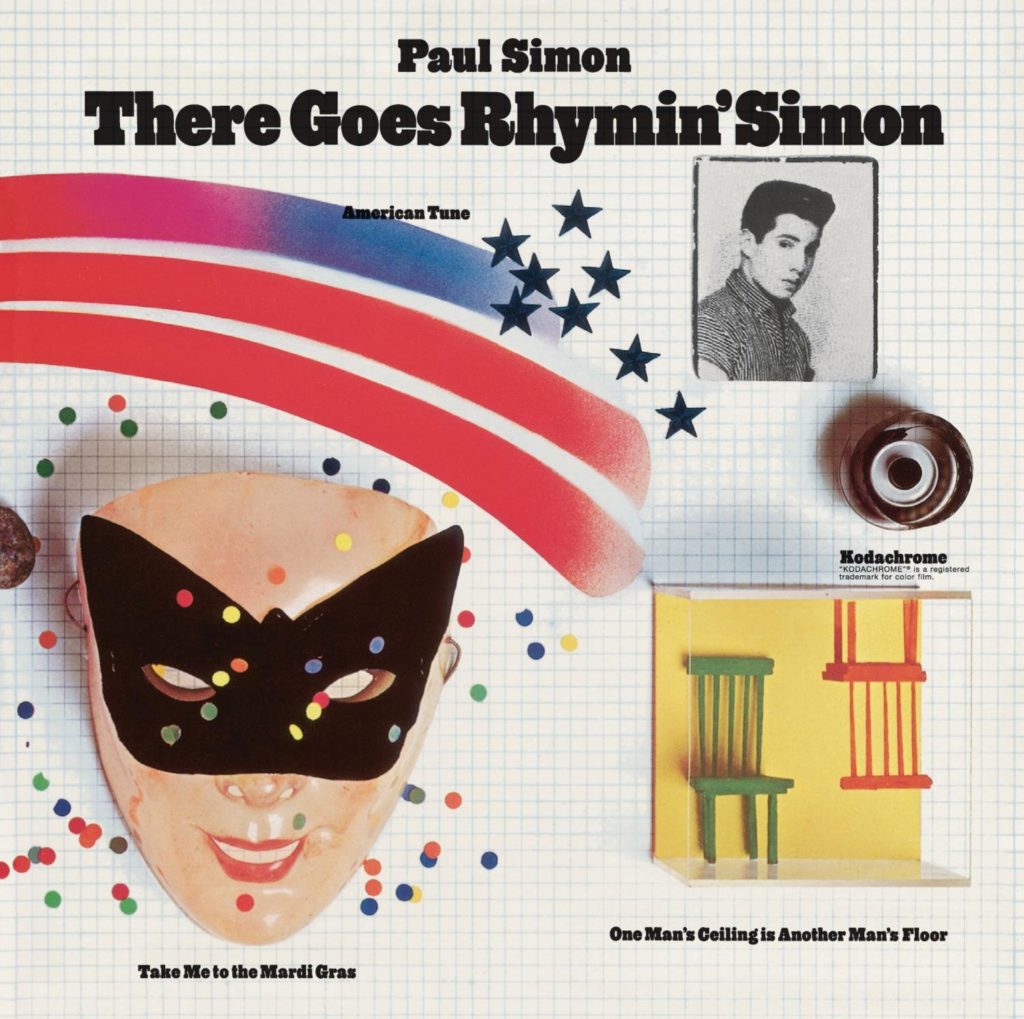

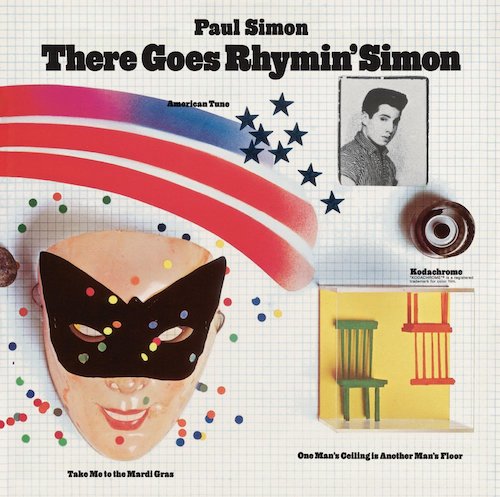

There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, released on May 5, 1973, was a massive hit, peaking at #2 on Billboard’s album chart (George Harrison’s Living In the Material World beat it out for #1). The album spawned six pop singles, the first two nearly Billboard Hot 100 toppers: “Kodachrome” and “Loves Me Like a Rock” both got to #2, bested only by Billy Preston’s “Will It Go Round in Circles” and Cher’s “Half- Breed.” The album’s gone platinum many times over; in 2004 an expanded CD reissue included interesting demos of “Let Me Live in Your City,” “Take Me to the Mardi Gras,” “American Tune” and “Loves Me Like a Rock.”

Simon’s followup, Still Crazy After All These Years, continued his winning streak, but was made in more turbulent circumstances, as he and Peggy divorced and the Watergate scandal finally led to Nixon’s resignation in August 1974. Simon has made vital, challenging music in a variety of styles for the past four decades, and pursued a number of philanthropic ventures, rarely out of the limelight. As of this writing, he’s won 16 Grammys, been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and continues to make excellent albums, although, unlike his only serious still-active songwriting rival Bob Dylan, he finally swore off the incessant concert touring in 2018. Don’t call Paul Simon “retired”—as he’s said, “I love making music and my voice is still strong.”

[The album—and other Simon recordings—is available here.]

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

4 Comments

It has always saddened me that Simon and Garfunkel just couldn’t get along. Egos (and presumably money) seem to be obstacles too great to overcome. But they sure made some great music together back in the day, didn’t they?

v2787,

Ditto that.

As the saying goes,

“the whole is greater than the sum of parts”.

Would have been nice to see them continue as a duet longer than they did.

It’s water under the bridge now.

One of the greatest lines in rock: “…my lack of education hasn’t hurt me none.”

The wit in Simon’s lyrics adds to their magnificence. Check out the pre-S&G “Lone Teen Ranger”. Who knew?

A friend was commenting just the other day that he didn’t think Paul Simon’s songwriting wasn’t as good after the Garfunkel departure. I rather strongly disagreed, and told him two of my favorite Simon compositions are “Kodachrome” and “American Tune”. I think my friend probably meant that the Simon songs performed when he was with Garfunkel came across better because Artie had THE VOICE, but “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon” is just an absolute classic with so many highlights.