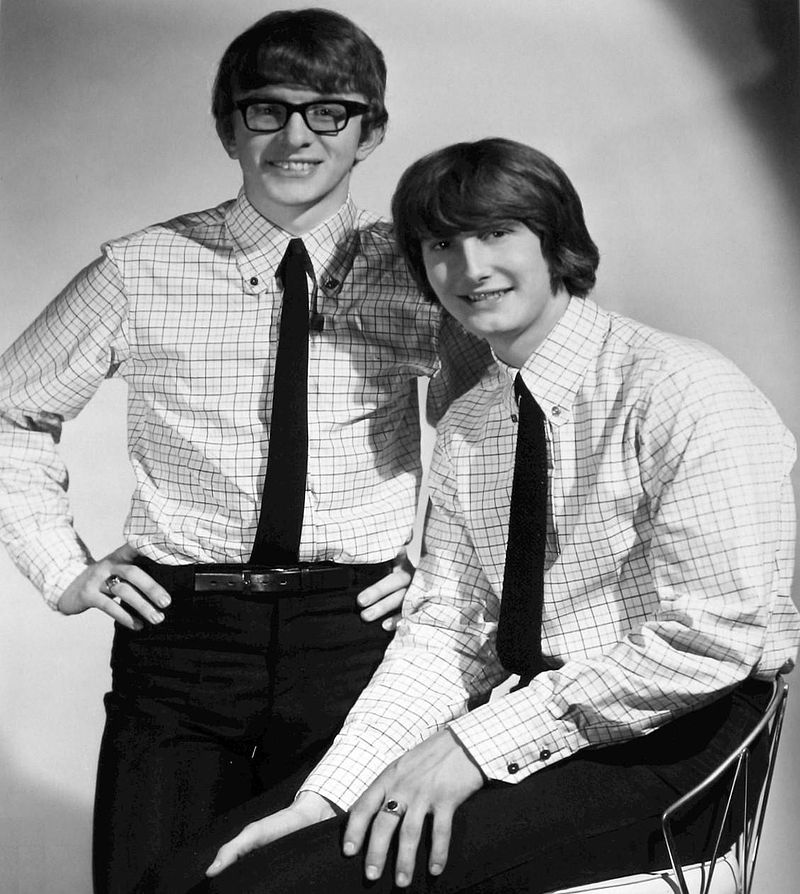

If you listened to popular music in the 1960s and ’70s, you knew Peter Asher. He first came to our attention via the British Invasion as half of Peter and Gordon, riding the Lennon-McCartney composition (well, McCartney only, but that’s another story) “A World Without Love” to the top of the charts in America in the spring of 1964. The duo—Asher with his flaming red hair and Buddy Holly glasses, and singing partner Gordon Waller) followed it with another half dozen top 20 singles, including three more McCartney-penned tunes: “Nobody I Know,” “I Don’t Want to See You Again” and “Woman” (written under the pseudonym Bernard Webb).

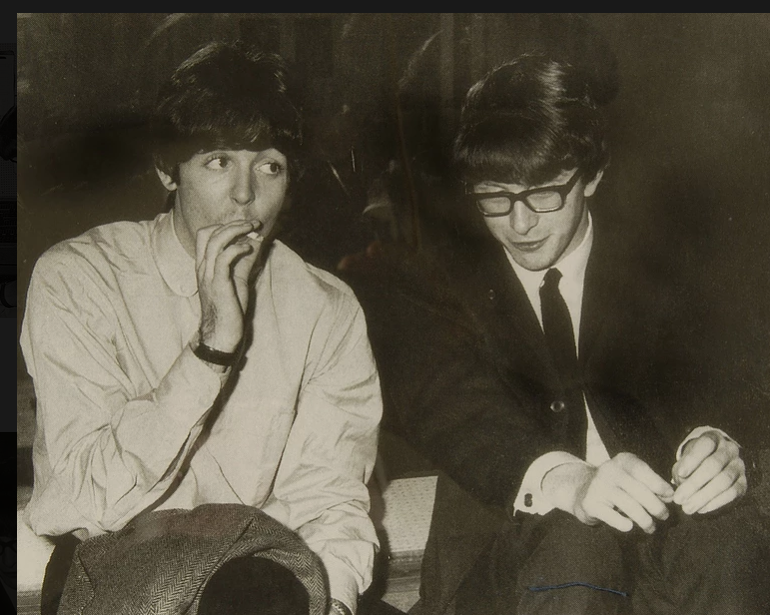

When Peter and Gordon ran aground in the late ’60s, Asher—whose sister Jane was dating Paul McCartney at the time—went to work for the Beatles’ Apple Records, heading up the A&R department, where he signed, among others, an unknown American folk singer named James Taylor. Asher produced Taylor’s debut album and then moved to the U.S., where he was directed toward former Stone Poneys singer Linda Ronstadt, whose management and production he also assumed.

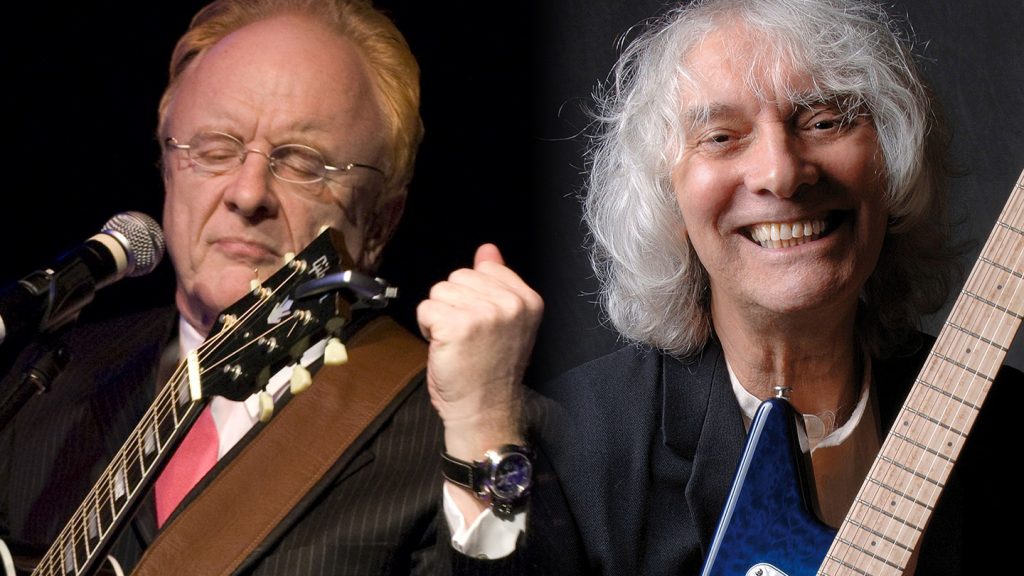

Asher, born June 22, 1944, has had a remarkable, fruitful career for more than five decades. Today he often performs live in intimate venues (sometimes with guitarist Albert Lee), recreating the music in which he was involved and telling stories from the heyday of the London and Southern California music scenes.

This interview took place in 2010, not long after Gordon Waller died on July 17, 2009, and until now most of it has remained unpublished.

Who produced the Peter and Gordon records?

The first ones were produced by Norman Newell. He’s the man who found us. We were playing a place called the Pickwick Club in London, which is a late-night drinking and eating pub. We would sit on bar stools and play acoustic guitars. It was there that Norman Newell, a very traditional A&R guy, invited us over to his table. He gave us our audition and then gave us a record contract and set us up for our first recording date. At the time, they were imagining us a little more in the folky vein, more of an English Kingston Trio, Peter, Paul and Mary thing. In fact it was a song called “500 Miles” that we used to do. We had a nice version of it that they thought could be a single. Norman was producing that session and that session grew to include “A World Without Love.” So he produced that session, which was “A World Without Love,” “500 Miles” and a few others. I think that’s all he did. Then we moved on to John Burgess, who was more of a proactive producer. Norman was really nice but pretty much left it to us. He had produced a few very successful records. He did the U.K. hit version of “Moon River,” for example, which was Danny Williams, no relation to Andy Williams. Norman was more middle-of-the-road, less rock ’n’ roll. Through whatever internal politics, we then ended up with John Burgess, who was more hands-on. He produced certainly all of the hits from then on.

Were they all done at Abbey Road?

Yes, at EMI Studios.

Watch Peter and Gordon perform “A World Without Love” in 1964

What did you learn during this period that you drew upon in your own productions?

A great deal. Obviously, I learned the technology of it. I’ve always been of a technological, scientific bent. I learned a lot about the process. At the time it was all half-inch Studer [tape recorders] and 4-tracks. I learned what limiters and compressors and microphones did. Watching Norman and John, I also learned different easy-to-relate-to artists and musicians and arrangement ideas. Many of these records had arrangers attached, and some didn’t. Our first session there was no arranger; it was us. Later on, Geoff Love, who did orchestrations, was involved. A couple of tracks we did, John Paul Jones [later of Led Zeppelin] wrote some arrangements. I ran into him not long ago—I hadn’t seen him since back then—and he reminded me of some particular jazz thing he’d done using some great British jazz players—Tubby Hayes, who was a legend on the British jazz scene. We were both jazz fans. It had nothing to do with either of our careers but we were both big fans.

Knowing what you know now, were those well-produced records?

Yes, they were. People ask me often which is my favorite and I think one of the reasons “I Go to Pieces” [P&G’s cover of a Del Shannon tune] is my favorite is because the arrangement, the production and the way we sang it all came together to make a good song into possibly a great record, are certainly a hit record.

“True Love Ways,” the Buddy Holly song, is also an epic.

Yes. By that time I was playing quite a role—not officially but the idea of taking that song and making it big. It was Gordon’s idea to do it. I was a Buddy Holly fan but he was a Buddy Holly aficionado. He knew everything. He sang it so well and so differently than Buddy—in Gordon’s big, resonant Elvis voice—that that’s where John Burgess and I got the idea of making it huge.

Gordon passed away recently. What is your most prominent memory of him?

That he was big-hearted. He could be grumpy but he was friendly with everybody. He was also an underrated singer—extraordinary voice. We sounded completely different. He had this big, resonant Elvis-y voice and I’ve got this choirboy tenor, English white un-soulful voice. But they worked together.

Did you produce any of the Peter and Gordon records?

No. The first record I ever produced was Paul Jones, from Manfred Mann. Brilliant singer and one of the best harmonica players in the history of the world, in my view. I owe him a debt because he was the one who watched me during some of these Peter and Gordon dates—he was a good friend—and he asked me if I would produce some tracks with him. There was a song called “And the Sun Will Shine,” which was a single we did. I wanted to get a really good rhythm section so I used Nicky Hopkins on piano, Paul Samwell-Smith from the Yardbirds on bass, Jeff Beck on guitar and Paul McCartney on drums. The B-side is a less memorable song, but Jeff Beck has some unbelievable soloing. It’s on a Paul Jones compilation.

And you just went in cold and did it?

Exactly. And to this day I think that being prepared is half the battle. I spent a lot of time figuring out how I wanted it to be. That of course is how Paul [McCartney] asked me to produce at Apple, which was what he asked first, before he asked me to be head of A&R for the label.

And that was not an offer you were about to refuse.

No, exactly. What could be cooler than working for a great new record label and for the Beatles?

Is it true that James Taylor just walked in the door one day?

Yes. He phoned first. The connection was [guitarist] Danny Kortchmar. He’d been in the Kingbees, backing Peter and Gordon, and then after we stopped touring and I was producing and starting the job with Apple, he was in a band called the Flying Machine with his old friend James Taylor. They were friends from Martha’s Vineyard, since they were about 14. When that band broke up, Danny gave James my phone number in London. James was planning to go to London just to check it out—I think he had a girlfriend over there at the time, as I recall. So James phoned and said, “I’m Danny’s friend and I’ve got this tape.” He came over and played me the tape. I don’t think he knew that I’d just gotten this new job, just that I was a friend and a producer. I was super impressed and I said, “It so happens I’m now running this new label. Do you want a record deal?” And he said, “Yes, please.”

You must have received thousands of tapes at Apple, but this one stood out?

I’m not so sure of the timeline but James was there right at the beginning. By the time we really moved in to [Apple headquarters at] Savile Row and took out the ad that said “Send us your tapes, we promise to listen,” we’d already had James. But yes, he stood out. He came in early and he was just incredibly good. And 99 percent, probably close to 100 percent, of the stuff we were getting in the mail was crap. We never did sign anything from the totally unsolicited tapes.

Listen to James Taylor’s original “Carolina on My Mind,” produced by Peter Asher

What was the setup like when you recorded that first album with James? What kind of equipment were you using?

It was 8-track, at Trident Studios on Soho. So it was a Trident board. The co-owner of the studio, Barry Sheffield, was the engineer. It was interesting because before everything had been 4-track. Indeed, when Paul came in to play on [Taylor’s] “Carolina on My Mind,” that was his first-ever experience with 8-track. It later would turn out that EMI [Studios] had actually had one the whole time, that they were testing, but nobody was using it. But Paul came over and worked in 8-track on the album, then he subsequently brought the Beatles over and they did “Hey Jude,” at Trident—that was their first 8-track recording.

Did you really need eight tracks for James?

Did you really need eight tracks for James?

We did for that one. The next album, Sweet Baby James, less so. We put a lot of strings and horns and percussion, so we used the tracks. A big plus was that we didn’t have to do the bounce-down. You’d go to four and bounce down to one, and then bounce down to one again, which is why the stereo mixes end up being so bizarre. Seventy-five percent of your stuff is on one track, so you have to put it on one side or the other, or the middle. That’s why the mono mixes of all those early records are the only ones to listen to. We never took the stereo mixes seriously because they sounded weird. People go, “Oh, how cool, they’ve got all the vocals here and all the instruments there.” We hated it! It was silly. So one of the big pluses of 8-track was it enabled us to make a real stereo mix.

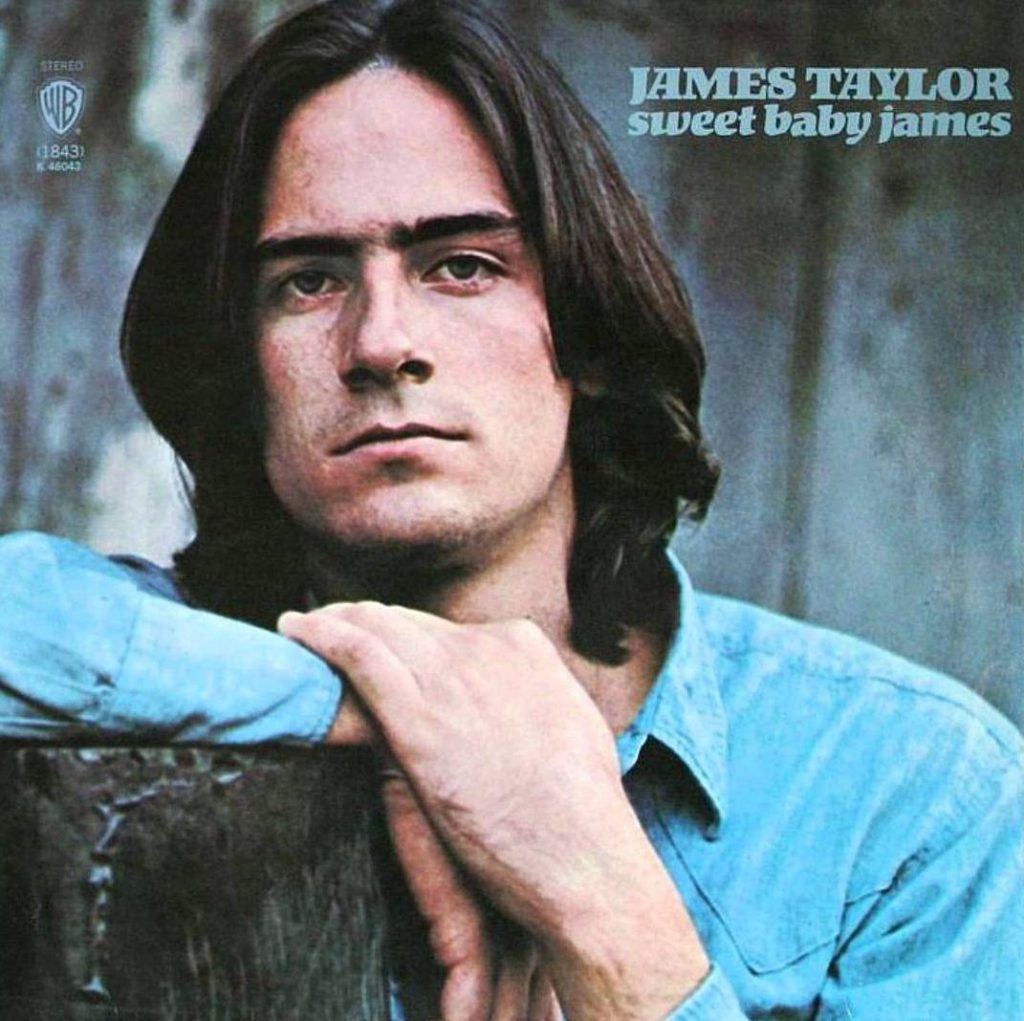

James exploded after that first album and became an amazing songwriter. What happened that Sweet Baby James touched so many people where the first album didn’t?

I think he was already an amazing songwriter—“Something In the Way She Moves” and “Something’s Wrong” and “Knockin’ Around the Zoo” and “Carolina on My Mind.” I think he came fully formed as a genius songwriter, just like McCartney did. You get better and more sophisticated and you learn more but good is good, and he was good. What happened to James? He just practiced more and wrote more and got better.

Where was Sweet Baby James done?

That was done at Sunset Sound on Sunset Boulevard. Bill Lazerus was the engineer. That was also 8-track and much simpler. We rehearsed every day at my house—it was a rented house with a giant pool and a guesthouse. The house was empty but we had a big sitting room with a piano in it and a stereo. We’d rehearse two or three songs in the afternoon, then go over to Sunset Sound and record. The whole thing was done in about two weeks.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Sweet Baby James

Did you use the same method as for the debut?

No, the Apple album was more elaborate. For that one we took an ad in the Melody Maker and hired musicians and then rehearsed and went into the studio. But I had more elaborate production idea for that record, based upon my determination that people would take James seriously and take the songs as being different. I was very concerned that people would say he was just another folk singer—the term singer/songwriter had yet to be invented. If you played acoustic guitar and had long hair you were a folk singer. When it came to Sweet Baby James I think I realized that perhaps I’d overdone it a bit. So I came out to L.A. and assembled the band. We brought in Carole King on piano because I loved her piano playing. Kootch [Danny Kortchmar] was of course a given on the guitar. I found a drummer, Russ Kunkel, who was not a studio drummer at the time—he’d never done a session. And then we used a few different bass players. It cost $7,600.

How did you achieve such an intimate sound on that album?

James’ voice is at its best when he sounds like he’s telling you a story sitting opposite you in your living room. I consciously wanted it to communicate to people the way that, when James played me a new song, I went, “My God, that’s good.” We definitely wanted it not to be a big, glossy record that distances you from the artist. I wanted it to be something where people would know James meant it.

Related: Read BCB’s review of a 2016 Peter Asher/Albert Lee performance

Were you developing a signature production style by that time?

Did I realize that? I can say unequivocally no. Was I? Maybe. I don’t know.

Are you a hands-on producer or more the kind who likes to keep a distance and encourage the artist to find his or her way?

I’m very hands-on but not to the point of interfering with some creative process that is going well. I think it’s the producer’s job to prepare stuff in advance, cost it correctly, get the right musicians, the right engineer, the right mood, the right place and the right time. I’ll often have preconceived ideas on how the track should come out, but I try not to let that get in the way and at least listen to what other people come up with because there’s no point in hiring great musicians if you’re going to make them play only what you had in your head. I think it’s important to know when to stop, knowing when to abandon a particular idea because it’s not working, knowing when you’ve got the take and when to say that’s enough and when the whole song isn’t working. You want to keep it going.

Have you ever had an occasion when something great came out of the musicians just fooling around during a break?

Yes, [Taylor’s cover of] “Handy Man.” We were in the middle of doing some other song and Kootch and James invented this slow version of “Handy Man.” I remember specifically saying, “Let’s stop what we’re doing. Let me put this down.” I think Russ was playing a cardboard box or something and then it was two acoustic guitars and the vocal. Probably Lee [Leland Sklar] was playing bass, and there was a background vocal.

You branched out into managing James. Was it difficult to balance those tasks?

Well, the producer and the manager didn’t get into any arguments! I didn’t find it to be a conflict. At the time it was not common at all. I liked doing both and it seemed to work for James and for Linda.

Related: Asher talked to us about producing Linda Ronstadt and others

Asher has written a book about his friends: The Beatles from A to Zed: An Alphabetical Mystery Tour. The hardcover book was published in 2019 by Henry Holt & Co. Order it below.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

1 Comment

Just saw Peter and Jeremy Clyde at the Kate in Old Saybrook, Ct. The show was great. Peter is getting a little slower, but the stories are always fun to hear. Jeremy of Chad & Jeremy is a surprising standout. My fave is “Go to Pieces” too.