Some tales of longevity begin with establishing a foundation and building steadily upon it; others involve stubborn determination and sheer elbow grease as things fall apart. Consider as an example of the latter an act of little renown, its lead singer and then-primary creative engine in prison, its record deal evaporated, and its most recent album gone with a whimper. Staring down that scenario, plenty of bands would call it quits.

Some tales of longevity begin with establishing a foundation and building steadily upon it; others involve stubborn determination and sheer elbow grease as things fall apart. Consider as an example of the latter an act of little renown, its lead singer and then-primary creative engine in prison, its record deal evaporated, and its most recent album gone with a whimper. Staring down that scenario, plenty of bands would call it quits.

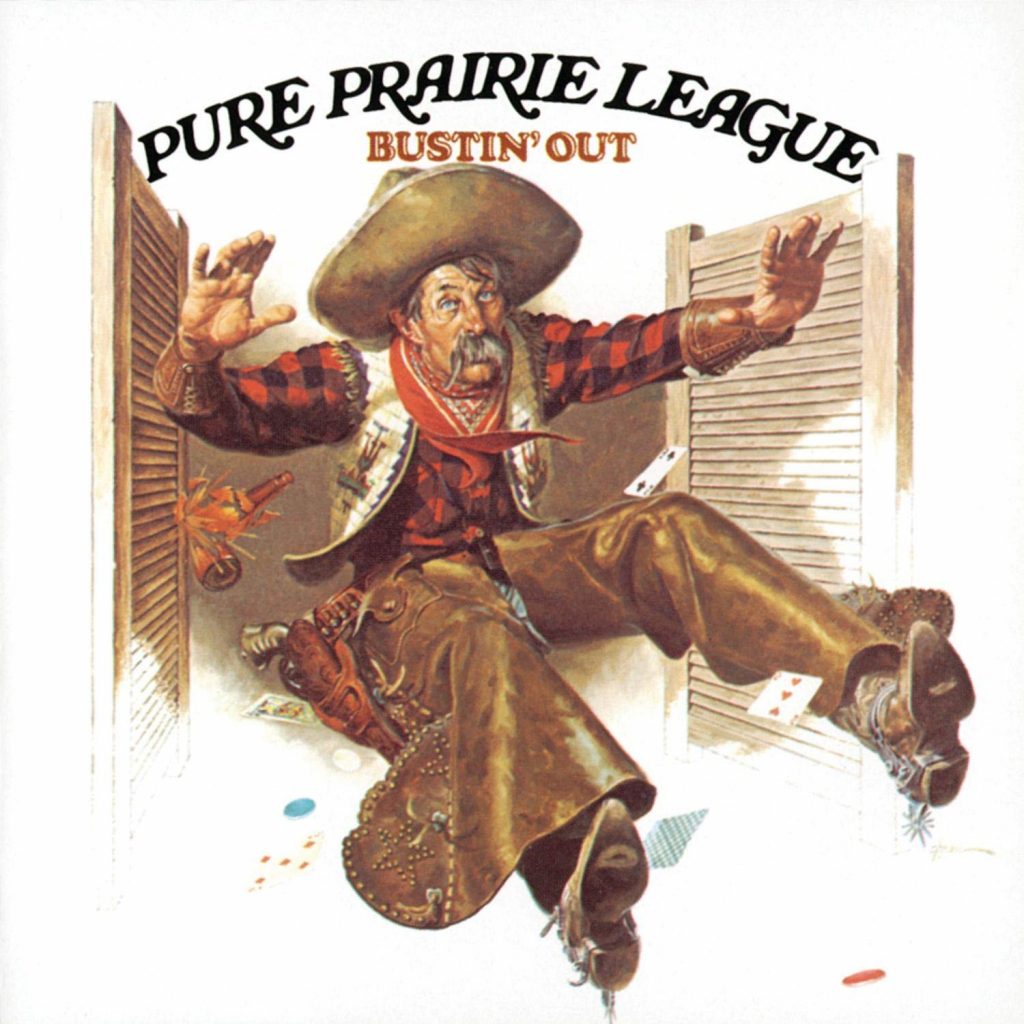

Pure Prairie League, on the other hand, soldiered on, eventually achieving a result akin to a country song played backwards; revived that dead album’s fortunes, got their record deal back, and kept the band together in one form or another for most of the last half-century. That’s the story of the band’s 1972—and then 1975—classic, Bustin’ Out.

Pure Prairie League got its start in Ohio in the mid-1960s with a group of musicians who had played together in multiple local bands. The first iteration of the group under that name formed in 1970, and by mid-1971 experienced its first—and not nearly last—substantial turnover, losing its rhythm section. That left Craig Fuller (vocals, guitar), George Ed Powell (vocals, guitar), John David Call (pedal steel guitar and more) and Robin Suskind (guitar, mandola), who were joined by drummer Jim Caughlan and Jim Lanham on bass to form the lineup in place for the band’s first album following its signing that year by RCA.

That debut was released in March 1972, with a cover that featured a Norman Rockwell painting originally used as the cover for the August 13, 1927, Saturday Evening Post, a depiction of a cowboy who would become a sort of Pure Prairie League mascot, featured in new illustrations by other artists on all its future collections. The band immediately began touring in support, its workhorse nature common to every lineup, and by summer set to work on its next album. Along the way, it had to deal with more upheaval, as Suskind left the band, and in short order Call, Caughlan and Lanham departed. The group’s eponymous debut gained little traction along the way.

With Fuller as the band’s leader and Powell a sort of second-in-creative-command (plus co-producer), the group brought in Billy Hinds on drums and worked as a trio augmented by session players (among them Al Brisco on steel guitar and Michael Connor, beginning a long affiliation with the group, on piano) for an album they would soon record in Toronto (Michael Reilly would join on bass following its completion). Needing to show results to RCA after their first record’s quick fade, they set to work on what would become Bustin’ Out, which would reach stores in October 1972, just seven months after their first record.

With Fuller as the band’s leader and Powell a sort of second-in-creative-command (plus co-producer), the group brought in Billy Hinds on drums and worked as a trio augmented by session players (among them Al Brisco on steel guitar and Michael Connor, beginning a long affiliation with the group, on piano) for an album they would soon record in Toronto (Michael Reilly would join on bass following its completion). Needing to show results to RCA after their first record’s quick fade, they set to work on what would become Bustin’ Out, which would reach stores in October 1972, just seven months after their first record.

Fuller composed all but two songs on the set, and one of them is the record’s opening track, a version of Chicago folkie Ed Holstein’s “Jazzman.” It opens with Fuller’s voice, a shimmering, high-tone pleasantry, which is soon wrapped in easygoing acoustic guitar filigree and the soft keening of Brisco’s pedal steel guitar. It is very much a country song, as flavorful as it is deliberate, as Fuller floats through its spacious reverie.

Angels get their due and then some on the set, beginning with the airy churn of “Angel #9.” Pushed by a firm but relaxed electric guitar spine, its supple bob is typical of the group’s understated brand of country rock, offered as a cool flow. The similarly titled “Angel,” on the other hand, is more of a graceful contemplation sequenced in the album’s penultimate position, and adorned by gently rendered vocal harmonies and a memorably mellow guitar interlude on a track that cross-pollinates bluegrass sensibilities with mainstream structure.

Powell’s lone composition on the set is “Leave My Heart Alone,” for which he provides a vocal lead that is less airy than Fuller’s sound, but not radical as a departure. The tune’s springy groove delivers a charming weave of acoustic, electric and pedal steel guitars, with added punch courtesy of a Dianne Brooks response vocal. Despite never seeing formal release as a single, the tune would in later years receive substantial airplay in AOR environments.

The group’s best qualities flow freely from “Early Morning Riser,” as Fuller keeps an even keel amid an easygoing ramble, never competing with its decorative guitar flourishes but always maintaining his place. He is equally at home amid the patient gear-shifter “Falling In and Out of Love,” sounding melancholy without losing his charm, and floating into an embraceable refrain that highlights the simple appeals of vocal harmony. The latter tune also makes for a memorable companion piece, using its last 15 seconds to foreshadow the track into which it so comfortably segues.

That tune is “Amie,” which would deservedly become the band’s signature track in the years to come. Its toe-tapping bob is a lovely example of country-rock comfort food, following a lively picked acoustic guitar jangle into Fuller’s relaxed vocal, paced by Hinds’ soft drum rattle and the subtle accent of electric guitar picking. Its understated chorus harmony is a rich enticement, and the track’s buoyant acoustic guitar fill provides a detour that amplifies its bob’s grabby appeal. A simple song with accents that stick (including Fuller’s enthused, “Longer if I do, yeah now!” to punctuate the final chorus), it works all the way to its lyrical callback to “Falling in and Out of Love” at its close—an inclusion that would later see many stations play the tunes as a paired entry, though not nearly so often as, say, “We Will Rock You/We Are the Champions.”

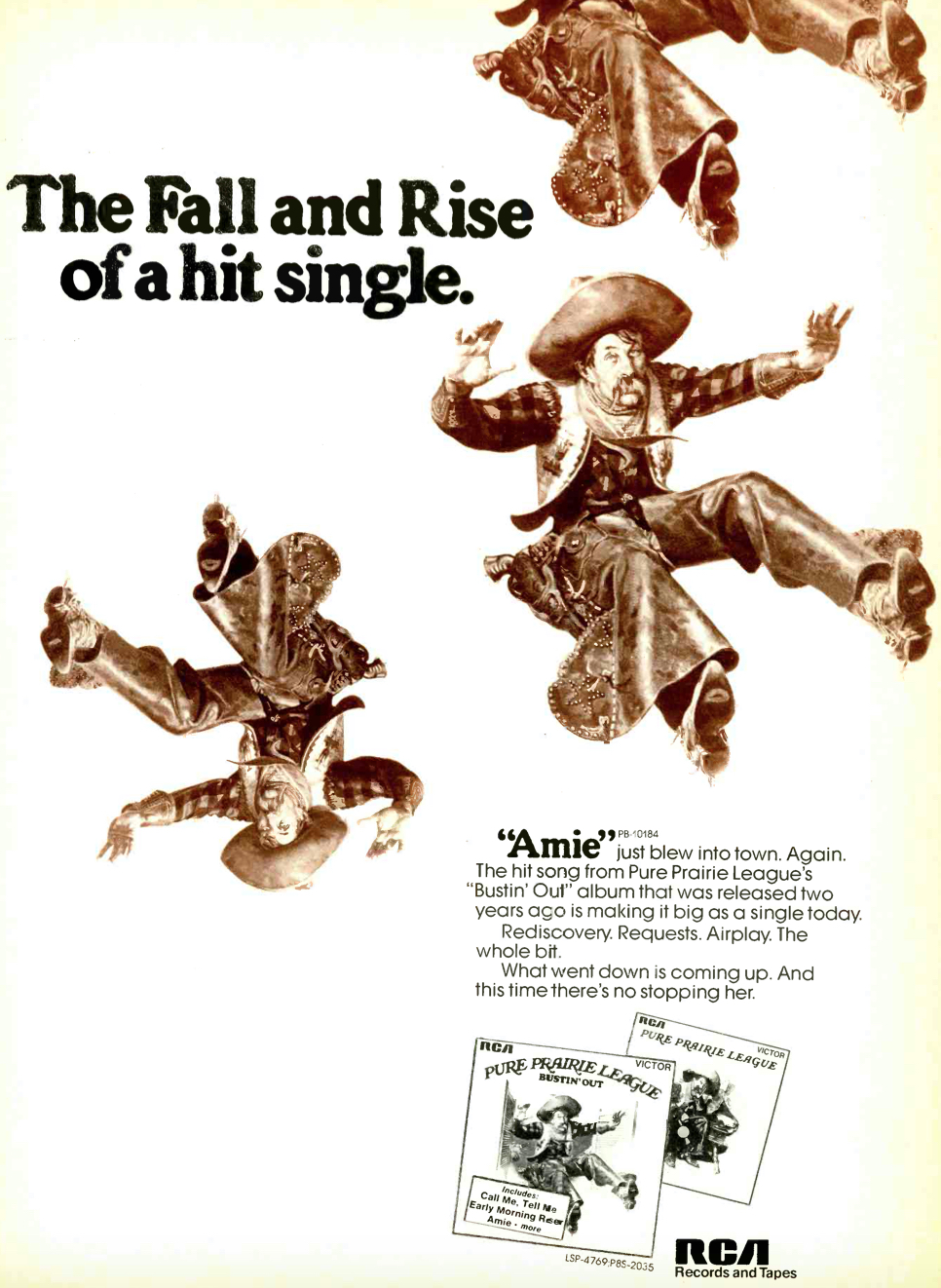

Although hearing the songs back to back does make each seem part of a larger whole, that last lyric fits well enough in the flow of “Amie” that the context of the previous song really isn’t necessary for it to work. Released as a single in 1973, it generated little interest…but that was not its story’s end.

The band’s formula changes on a pair of tunes due to string arrangements contributed by Mick Ronson, at the time a member of David Bowie’s Spiders from Mars. In “Boulder Skies,” his piece of the puzzle is complementary to the band’s baseline approach, adding sonic depth and making for a rich enhancement of Fuller’s vocal caress. The effect is understated, but augments the entire track.

On the other hand, the album-closing “Call Me, Tell Me” is virtually defined by Ronson’s presence. Opening with a pulsating acoustic backbone, it belongs at that point to the same family as the rest of the album, but soon becomes something else. Fuller’s vocal is heartier than elsewhere, but deliberate and steady, even as atmosphere builds around him. The strings themselves land front and center in the arrangement, and make the song feel like conventional rock, less homespun than the material with which it is preceded. Perfectly functional on its own, the song nonetheless represents a curious departure with which to leave listeners, as if the weightiness of its flourishes is meant to wash away what came before. As a coda to a record with a compelling sonic through-line, it feels almost like it belongs on a different record.

Soon after Bustin’ Out reached stores that October, the band faced a large hurdle. Fuller, who considered himself a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, was found guilty in Kentucky of evading the draft, and sentenced to six months in prison—President Gerald Ford would later pardon him, but at the time it was a devastating blow. In February 1973 he departed the group, and with no real way to support their then-new record, RCA decided to cut its losses and dropped the band.

Even then, those still in place found a path forward. By late summer, Call returned, and Reilly took over Fuller’s spot as frontman. Fuller decided not to return after leaving prison, so they brought in Larry Goshorn to take Fuller’s role, handling vocals and guitar. Restored to a full lineup, they again toured heavily, working the college circuit hard, and built a fan base that led to their music receiving support on college and commercial radio.

“Amie” proved a popular choice at those stations, but no one knew what to do with that fact until Patti Smith Group guitarist Lenny Kaye suggested that the label re-release it. Second time proved to be the charm, as the song climbed as high as #27 on the Billboard Hot 100 in April 1975. The band had re-signed with RCA, for which they would release Two Lane Highway in June of that year, and Bustin’ Out proved a delayed success, reaching #34, the first of four straight Top 40 albums for the group.

Related: 10 re-released songs that became hits

Pure Prairie League would change its lineup many times in the years that followed—most notable, following a near-total exodus in 1978, was the hiring of a young Vince Gill, who would be with the band three-and-a-half years, and lead vocalist for its 1980 saxophone-draped tweener hit “Let Me Love You Tonight,” which at a peak of #10 (and topping the Adult Contemporary chart) would represent the band’s greatest chart success. The group went dormant for a decade starting in 1988, but otherwise has existed in some form since its inception, with Reilly the primary stalwart, and Fuller and Call returning for substantial periods along the way. Each new iteration has been distinguished by its steady presence on the road, pursued with the same dogged determination that revived the fortunes of its second record and kept it from becoming a lost classic.

Watch Pure Prairie League perform “Amie” live on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert

9 Comments

“Amie” – many a campfires’ choruses we have sung (not always on tune, but we tried)

along with “Dixie Chickie”, “Friend of the Devil”,

Take It Easy”, and if course, “American Pie”, amongst many others.

Good Times.

Some songs you can hear too much (e.g. anything by the Eagles not titled “Teenage Jail/Greeks Don’t Want No Freaks”). Amie isn’t one of them. And you can sing along to it without sounding too horrible.

This is one of the best LPs of the early 70’s. I still listen to it on a regular basis.

Love “Bustin’ Out” in its entirety, but for any readers who may not be as familiar with PPL, do yourself a favor – Pick up a copy of “The Best of Pure Prairie League”, which touches upon many of their radio-known tunes, as well as some excellent deeper cuts.

Very enjoyable listening.

The two PPL concerts I saw in the 70s were very good. More recently they would open for Poco. At this point, PPL is a bar band.

I always thought Craig Fuller would become the next Jackson Browne. A great writer and also a great singer. He went on to form the band “American Flyer” with Eric Kaz, put out two good records. Then a short stent in “Little Feat” with a great album called “Let It Roll”. Very underrated. Fabulous tunes by Fuller.

busting out, and two lane hiway are the two sides of the coin known as pure prairie league… in my opinion…

For Thomas Kintner:

The Pure Prairie League profile is one of the best-written, most concise, and most historically accurate pieces I have seen in a long time. Well done, Tom !

Tell him you did a great job. I read and heard every bit of it and I enjoyed it thoroughly. Keep up the good work. Thanks again.