On May 11, 1974, having completed their third concert at the Uris Theatre in New York City as support band for Mott the Hoople, Queen should have been moving on to the next of 20 additional dates booked on their first tour of the United States. But their guitarist Brian May had been diagnosed with hepatitis two weeks earlier, and his health was failing. (He may have contracted the disease from a contaminated needle when he received mandatory vaccinations before traveling for Queen’s one-off Australian festival date in January.) The American tour in support of their Queen II LP had been a rousing success, but all momentum now ground to a halt.

On May 11, 1974, having completed their third concert at the Uris Theatre in New York City as support band for Mott the Hoople, Queen should have been moving on to the next of 20 additional dates booked on their first tour of the United States. But their guitarist Brian May had been diagnosed with hepatitis two weeks earlier, and his health was failing. (He may have contracted the disease from a contaminated needle when he received mandatory vaccinations before traveling for Queen’s one-off Australian festival date in January.) The American tour in support of their Queen II LP had been a rousing success, but all momentum now ground to a halt.

“When I was in the hospital, I found plenty of time to read the press cuttings that some of friends of mine had been keeping for me, and that really depressed me,” he later told journalist Rosemary Horide. “It was about that time I began wondering whether it was worth going on with music and the group. The thing about hepatitis is that it takes away all your drive and I was left feeling as if I didn’t have anything to contribute, as if it just wasn’t worth it.”

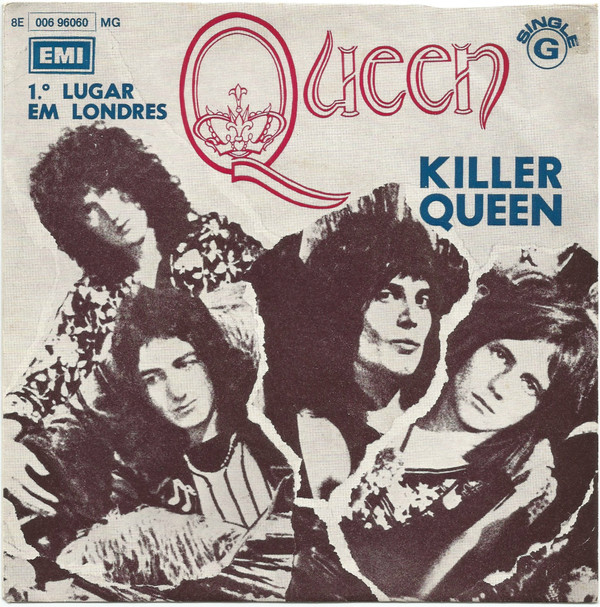

Without May, singer/keyboardist Freddie Mercury, drummer Roger Taylor and bassist John Deacon prepared new songs for a third Queen album, with rehearsals and initial recording sessions at Trident Studios in London. Mercury told Melody Maker’s Caroline Coon about his grace under pressure, with a two-week deadline: “Well, ‘Killer Queen’ I wrote in one night. I’m not being conceited or anything, but it just fell into place. Certain songs do. Now, ‘March of the Black Queen’ [from Queen II], that took ages. I had to give it everything, to be self-indulgent or whatever. But with ‘Killer Queen,’ I scribbled down the words in the dark one Saturday night and the next morning I got them all together and I worked all day Sunday and that was it. I’d got it. Certain things just come together, but other things you have to work for.”

In July, May was feeling well enough to join them at Rockfield Studios in Wales, completing most of the backing tracks with producer Roy Thomas Baker and engineer Mike Stone. But when they moved to Wessex Sound Studios in London, May was hospitalized again and required surgery, for yet another serious ailment: “When they found out I had a duodenal ulcer, I really thought that was the final straw. You see, instead of getting better after the hepatitis I just got sicker and sicker, and eventually they found out what was wrong. I was very down then.” But he came back to the group more committed than ever.

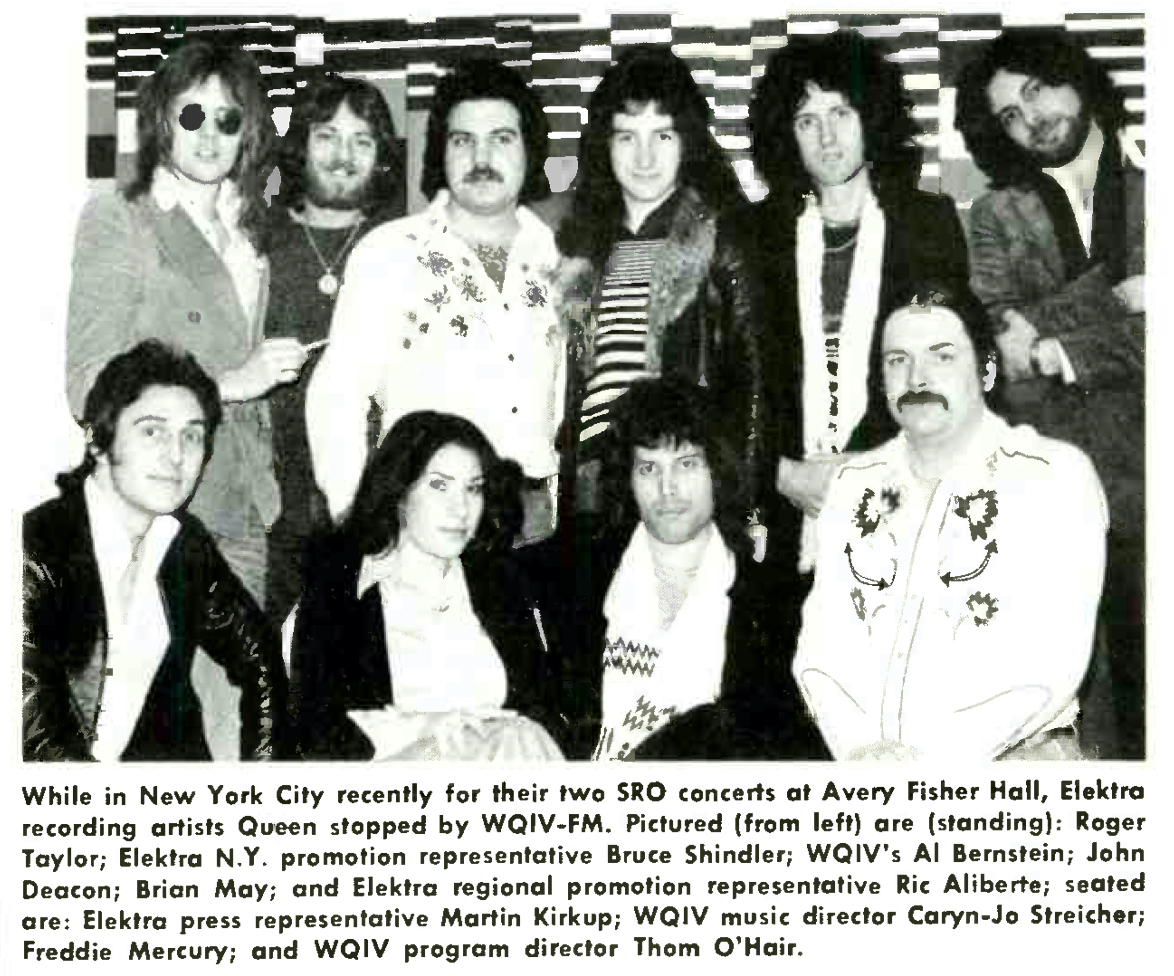

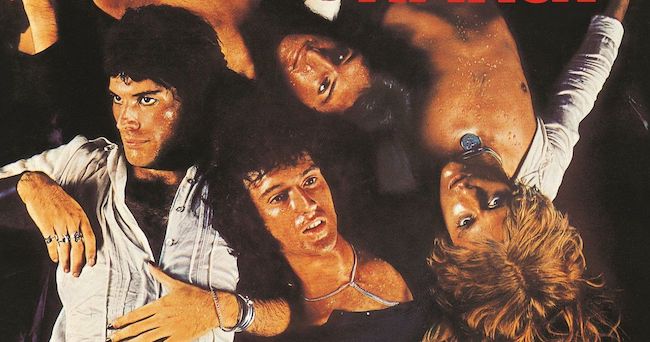

The resulting album Sheet Heart Attack — listed as being released on Nov. 8, 1974, though it was actually later that month by Elektra in the U.S. and EMI worldwide — was Queen’s commercial breakthrough. “Killer Queen” became a hit single, and the album made it to #12 in Billboard. Wildly theatrical, straddling the worlds of hard rock, pop, prog and Broadway, the album was an eclectic triumph. May later said it was the first album on which Queen sounded like a true band rather than four individuals; he felt the experience gained on tour in America made the whole sound gel. He hadn’t been able to write as much as usual for the sessions, but that didn’t matter, because, as he said in a 1975 interview, “I play my best guitar on other people’s songs.”

The opener “Brighton Rock” had been written by May during the Queen II sessions. It opens with the sounds of the holiday pier in Brighton before the band enters at a frantic pace, and Mercury at the top of his range screams the lyrics: “Happy little day, Jimmy went away/Met his little Jenny on a public holiday/A happy pair they made, so decorously laid/’Neath the gay illuminations all along the promenade.” Mercury then does an impressive sweep down to a lower octave, a trick he returns to several times during the track. A section of stacked vocals looks forward to “Bohemian Rhapsody” before May leads Deacon and Taylor into a swirling collage of metal-like chord slams and psychedelic ambiance. (How Baker and Stone captured the detailed sonic mayhem of Queen throughout their years of work with the band is amazing.)

At 2:40 of “Brighton Rock,” one of the greatest guitar solos ever recorded begins. May’s use of Echoplex delay and his alteration of light and heavy touch is jaw-dropping, and sets the template for every hard rock guitarist to come (listen to Eddie Van Halen’s “Eruption” for Exhibit A). When Mercury re-enters for the concluding verse, May sings with him, and the guitar pyrotechnics end it all with a thunderclap.

A bigger contrast to the next track, “Killer Queen,” can hardly be imagined. Finger-snapping and tack piano begin, with a stately mid-range Mercury vocal that owes its hybrid sangfroid to the British music hall and French chanson traditions. Expertly designed backing vocals swoop, “caviar and cigarettes/well-versed in etiquette/extraordinarily nice” is done in falsetto, and then the super-catchy chorus arrives.

Mercury revels in his tale of a high-priced prostitute who is “dynamite with a laser beam,” throwing in fancy words that rarely make it into pop lyrics: insatiable, gelatine, baroness. There are occasional phasing effects on the vocals, and May tries out a half dozen different guitar tones, with a middle overdubbed section that is a marvel. This is where Mercury’s fascination with the “spirit of extravagance” that is “camp” blossoms.

Another change of pace is Taylor’s folky “Tenement Funster,” which he sings very much in the style of Mott the Hoople’s Ian Hunter. Deacon played the acoustic guitars in May’s absence, but May added electric parts later.

It segues into Mercury’s “Flick of the Wrist,” which perhaps echoes Alice Cooper in its opening bars, and has a wonderfully unhinged middle section where frenetic drumming, multiple guitars and stacked vocals collide.

The joyful over-the-top antics yield to the third part of the medley, “Lily of the Valley,” a short, tender Mercury ballad that he sings the hell out of. This is another example of Baker’s production expertise: listen how the “sound of the room” caresses May’s guitar lines and keeps Mercury’s piano in front of your ears. (Queen albums, like Pink Floyd’s, pay dividends with good headphones.)

May closes out the first LP side with the massive “Now I’m Here,” which he wrote in the hospital. His chunky guitar riff is worthy of Led Zeppelin, even if it yields to a chugging feel that owes something (again) to Mott the Hoople. Mercury really sells it, and at 3:15 Dean, Taylor and May give a master class in how to lock in a groove and wail. As it ends, May goes into a fervid Chuck Berry-style solo, which Mercury verifies by singing “go, go, go little Queenie” before the fade.

The second side of Sheer Heart Attack is a mixed bag with some real clunkers. “In the Lap of the Gods” starts it off with an operatic scream, stacked guitars and heaps of harmony vocals (by Taylor and Mercury) sputtering in the mix before a very arch, highly-processed Mercury lead vocal emerges. He absolutely revels in the nuttiness, while May again pulls out a wide variety of sonic colors and combinations.

The two-minute blast of “Stone Cold Crazy” is next, sounding like the bastard child of Deep Purple’s “Highway Star” and Golden Earring’s “Radar Love.” Some commentators have said the beginning of “thrash metal” is right here, and they could be right. The song had been kicking around the band for years, in various arrangements, and nobody could remember who wrote the lyrics by the time they tried it again for Sheer Heart Attack, so it’s credited to all four members. It’s magnificently goofy. (A cover by Metallica won a Grammy Award for Best Metal Performance in 1991.)

May’s short ballad “Dear Friends” is beautifully sung by Mercury and leads into Deacon’s only solo writing credit, “Misfire,” which seems to have escaped from a Doobie Brothers album. “Bring Back That Leroy Brown” is a Charleston that Mercury leads on honky-tonk and grand piano, with a gazillion vocal overdubs. Deacon’s on double bass and May strums a banjo-ukulele, an instrument popular in the 1920s that fits Mercury’s retro lyrics and rhythm. In concert, the tune was most often treated as a throwaway instrumental; maybe it ultimately exceeded Mercury’s quotient for silliness.

“She Makes Me (Stormtrooper in Stilettos)” is written and sung by May, with Deacon on acoustic guitar along with him. There are echoes of the Who, the Association and the Eagles, and not a lot of Queen. There’s not much of interest here; the tempo drags, and the track really overstays its welcome at 4:08. There are some “New York nightmare” sounds, sirens and heavy breathing, that are just weird. Thankfully, “In the Lap of the Gods…Revisited” concludes the album in high style, a fantastic showcase for Mercury and May. It was Mercury’s first try at writing a melody line that audiences would enthusiastically sing along to, and he placed it as a show closer for many gigs in the next three years. Its role as a sing-along eventually was supplanted by a little ditty called “We Are the Champions.”

Sheer Heart Attack established Queen as a major force in most parts of the world and Mercury as one of rock’s most flamboyant frontmen. They did a world tour of 77 dates, and audiences loved them, from Manchester to Munich, Trenton to Tokyo. Most critics praised the album’s recording dynamics and the audacity of the conception, and admitted no matter how pretentious or bombastic, Queen were consummate entertainers. The triumphs of A Day at the Races and A Night at the Opera were still to come, but they have their roots in Sheer Heart Attack’s bravado.

Bonus Video: Watch Queen perform “Killer Queen” on Top of the Pops in 1974

Related: Our Album Rewind of Queen’s A Night at the Opera

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

2 Comments

to me this is the last great QUEEN…though many are quite good….the first 3 really blew me away

Great article, Mark. This is definitely an album for headphones. Or, dust off that stereo and give your speakers a workout.