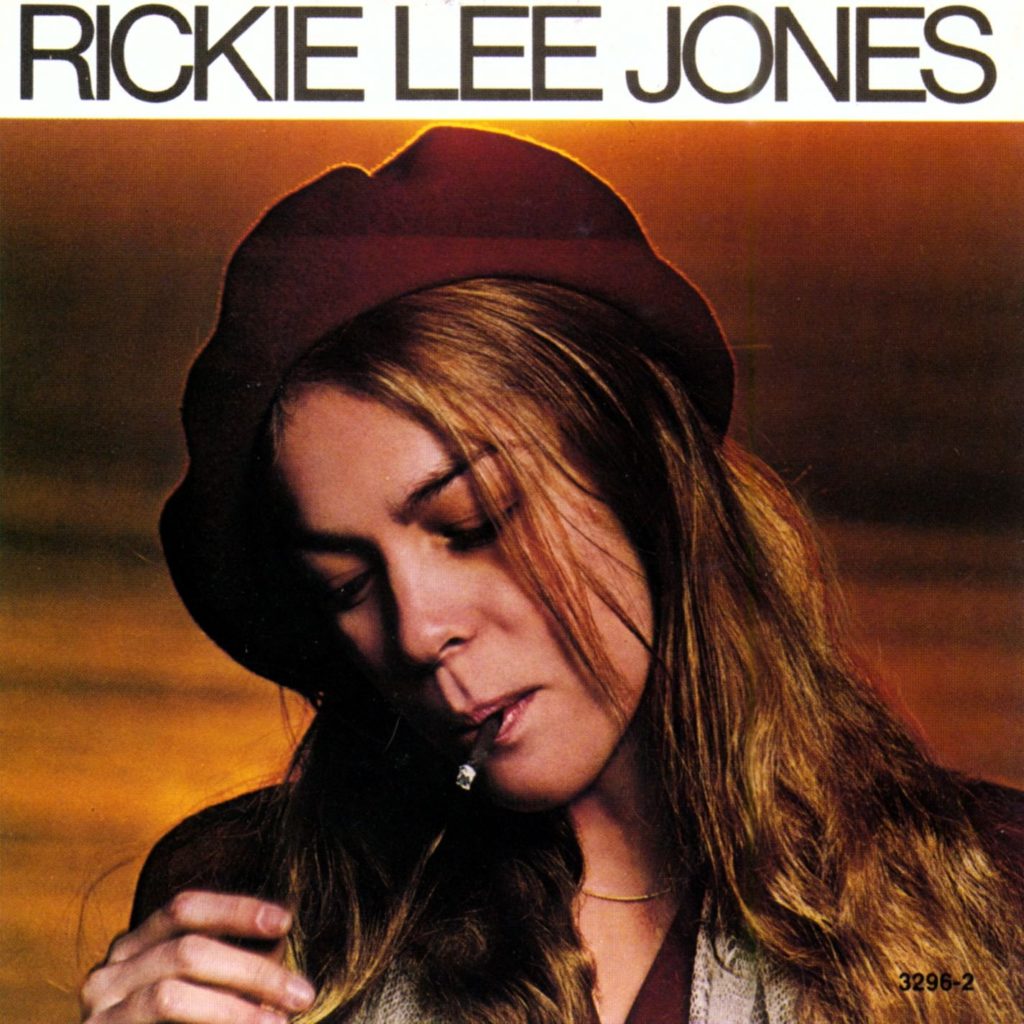

On her self-titled 1979 debut album, Rickie Lee Jones reached beyond folk, rock and blues influences then dominant among Los Angeles’ singer-songwriters, looking to earlier generations of songsmiths. Moving to Southern California earlier in the decade, the Chicago native distilled jazz, swing and mid-20th century pop lyricism into her songs, honing her material in gigs from Orange County to Venice as she cultivated a playfully bohemian persona set at a gritty, urban distance from Laurel Canyon.

On her self-titled 1979 debut album, Rickie Lee Jones reached beyond folk, rock and blues influences then dominant among Los Angeles’ singer-songwriters, looking to earlier generations of songsmiths. Moving to Southern California earlier in the decade, the Chicago native distilled jazz, swing and mid-20th century pop lyricism into her songs, honing her material in gigs from Orange County to Venice as she cultivated a playfully bohemian persona set at a gritty, urban distance from Laurel Canyon.

As a singer, she was mesmerizing, gliding from teasing whisper to urgent, full voice effortlessly, controlling her vibrato with the sureness of a great horn player. That sensibility, rooted in jazz, reveled in a love of pure sound coupled with an actress’ sense of timing as she served a varied menu of shaggy dog stories, jubilant uptempo romps, and introspective ballads with equal conviction.

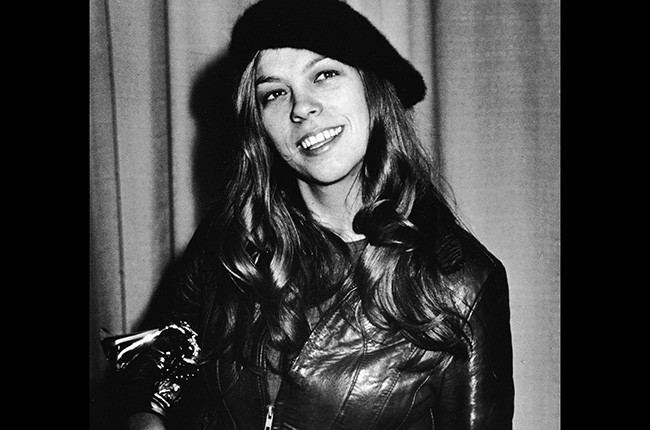

At 24, Rickie Lee Jones was a streetwise nomad raised in a troubled family with music in its DNA. Her grandparents were vaudevillians; her father, a World War II veteran, was a singer, songwriter, painter and trumpet player from whom she learned jazz and pop standards. The family moved to Arizona when she was five, then to Olympia, Wash., five years later, where her father abandoned them. At 14, she ran away to join him in Kansas City, Mo., before returning to the Northwest, dropping out of high school, then taking the GED exam to enter college in Tacoma. On her 18th birthday, in 1972, she moved to Huntington Beach, Calif.

Within a year, she was performing at showcases, in cover bands, or sitting in on local jazz sessions before making a fateful connection with Tom Waits, whom she met in 1977 at West Hollywood’s Troubadour, ground-zero for SoCal’s singer-songwriters. Their relationship underlined a shared embrace of Beat aesthetics and post-bop jazz. Together with Chuck E. Weiss, a sympathetic peer, they posed a retro contrast to the city’s reigning pop and rock cliques, more comfortable hanging with the punks at the Tropicana Motel than the cocaine cowboys at the Troub.

By 1978, Jones had gained significant fans in Dr. John and Little Feat’s Lowell George, readying his solo debut LP, on which he covered Jones’ “Easy Money.” Jones’ four-song demo stirred a buzz, followed by a bidding war, with Warner Bros. signing her. The timing was ideal for both artist and label: The Burbank label was already home to an impressive slate of singer-songwriters rivaled only Elektra/Asylum, while then building out a parallel roster of contemporary jazz artists with crossover clout. Rickie Lee Jones bridged both arenas.

Lenny Waronker, the Warner A&R chief who signed her, and staff producer Russ Titelman teamed up to produce Jones’ sessions, booking a phalanx of first-call pop and rock session veterans and seasoned jazz players. Jones played guitars, keyboards and percussion, and arranged the horn sections, while arranger Nick DeCaro and composer/arranger Johnny Mandel wrote string charts for sessions that ran from September through December of ’78.

From the opening downbeat, Rickie Lee Jones unspools with arresting confidence. A jaunty acoustic guitar figure, snare rolls and snapped fingers set up her sly, conversational vocal, a second-person address as she ponders whether “Chuck E.’s in Love” while sketching characters and wandering from poolhall to drugstore to “the Pantages” (theater), trying to identify the object of his affection. Curiosity gives way to confusion and then a grinning epiphany that he’s “in love with the little girl who’s singin’ this song.” Vocally, Jones pulls focus throughout, a deft storyteller aided by a spacious arrangement edged by Jones’ crisp horn charts and a solid jazz rhythm section that sound both fresh and timeless, anchoring the album in an opening track that would earn two Grammy nominations on its own and clinch her win as Best New Artist at the 1980 awards.

In pacing and mood, Jones and the producers pull off an impressive balancing act, moving between exuberance and melancholy, passion and amusement, adjusting the scale of the settings from larger ensembles to small groups without any missteps as she shifts from solitary vignettes to urban tableaux. “On Saturday Afternoons in 1963” is a hushed meditation on childhood, memory and identity, an interior dialogue with her nine-year-old self sung softly against a tolling piano and a haze of strings and subdued horns. Its graceful melody and spare chamber setting evoke the haunted ballads of Randy Newman, an acknowledged influence who repaid the compliment by playing on her album.

Jones’ cast of characters then introduces a young mother on “Night Train,” fleeing the threat of losing her child in song fusing nightmare with lullaby and conjuring the solitude of an empty train station in the middle of the night. “Young Blood” turns toward a nominally brighter cityscape peopled by the singer and her friends beneath the streetlights as they take “a walk around midnight in the city,” one where the streets are still mean but there’s a promise that “Love will wash you clean in the night’s disgrace.”

Characters like Pepe and Bragger, name-checked both in “Young Blood” and later on “Coolsville,” suggest a fellowship of street people inhabiting Jones’ neighborhood. “Easy Money” introduces “a couple Jills with eyes on a couple bills” and “an old Black cat…in an old black Cadillac” in a back-alley farce built around a con job that backfires in a karmic comeuppance part punchline, part parable. “Danny’s All-Star Joint” and “Weasel and the White Boys Cool” populate the set with another half-dozen denizens of the sleazy streets that run through her urban demimonde, a neighborhood that comes alive through Jones’ vivacious performance and the richly detailed arrangements.

Related: What were the best-selling albums of 1979?

Yet, if hipster camaraderie buoys Jones’ cityscapes, she also paints a desolate desert vista on “The Last Chance Texaco,” the album’s most dramatic performance. A daring poetic design riffs on “a long stretch of headlights,” truck stops, “sleepy diesel eyes” and an extended metaphor conflating a failing automobile with a doomed romance: “It’s her last chance/her timing’s all wrong/Her last chance/She can’t idle this long…”

Imagery that might invite a smile on the printed page is transformed by her performance and the stark yet elegant arrangement into authentic pathos, further establishing a command of dark, emotionally vulnerable ballads that provides Rickie Lee Jones with an enduring depth beautifully served by Waronker and Titelman’s bespoke production. The album, released on February 28, 1979, would ultimately reach #1 on the U.S. albums chart.

Jones would go on to further explore the emotional and stylistic poles established on her debut on her subsequent ’80s albums while sustaining a nomadic impulse in both her personal and musical lives, often leaning further into jazz whether on her own material or eclectic cover performances, a restless penchant for experimentation ultimately eroding her mainstream acceptance.

Bonus Video: Hear Lowell George’s performance of Jones’ “Easy Money,” recorded for the ex-Little Feat singer, songwriter and guitarist’s 1979 solo album

Jones’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024

1 Comment

One the best “first” albums ever. A masterpiece. What a band she had.