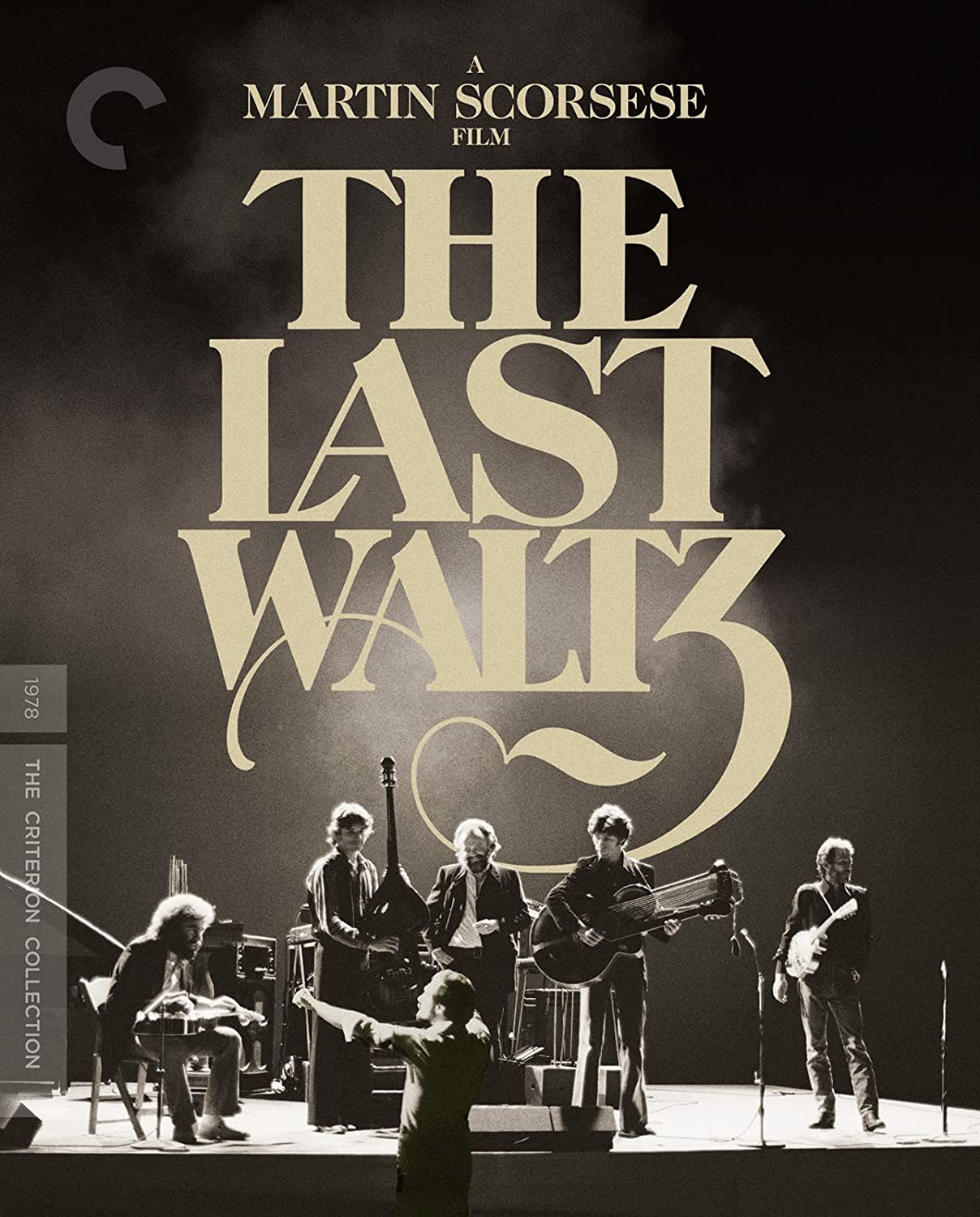

Director Martin Scorsese’s 1978 documentary The Last Waltz, capturing The Band’s 1976 farewell concert in San Francisco, received a 4K digital restoration in 2022 with audio commentary from Scorsese; the Band’s guitarist and chief songwriter, Robbie Robertson; and Mavis Staples of the Staple Singers, among others. It also includes a new interview with Scorsese conducted by critic David Fear, outtakes and additional footage. It’s available on Blu-ray and 4K UHD via the Criterion Collection.

Director Martin Scorsese’s 1978 documentary The Last Waltz, capturing The Band’s 1976 farewell concert in San Francisco, received a 4K digital restoration in 2022 with audio commentary from Scorsese; the Band’s guitarist and chief songwriter, Robbie Robertson; and Mavis Staples of the Staple Singers, among others. It also includes a new interview with Scorsese conducted by critic David Fear, outtakes and additional footage. It’s available on Blu-ray and 4K UHD via the Criterion Collection.

In the film, Scorsese and seven camera operators lensed epic performances by Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Ronnie Hawkins, Muddy Waters, Neil Young and others, in addition to The Band’s goodbye concert.

Other features of the Criterion Collection release incorporate a 1978 interview with Scorsese and Robertson, a 2002 making-of documentary about The Last Waltz, and an essay by writer and author Amanda Petrusich.

This writer had the opportunity to speak about The Last Waltz with Robertson in 2002 and 2017. The following excerpts are from those interviews.

Best Classic Bands: Did you have any doubts or fears embarking on The Last Waltz?

Robbie Robertson: Entering the event, big time, it was, “Can we pull this off?” There’s a thousand things that can go wrong, and a couple of things that can go right here. “Are we going to nail this? Is the film going to capture it? Are they going to say afterwards that the recordings are a disaster?” There’s all those technical concerns and just your ability to rise to the occasion and that moment. It wasn’t like we were stopping and doing the songs over and over, or, “I think we can do it better.” There was none of that.

The rehearsal tapes for the concert were discovered during the preparation for the re-release. What was it like to go back to those?

The rehearsals were a wonderful surprise for me, because I didn’t know that any of the rehearsals were even taped. What they were doing was testing the equipment and they just taped some of these things to make sure everything was working; they were judging whether they were using the right microphones for certain things. So, that was just a lovely surprise to hear, and also to hear the difference in what somebody might do when they’re working the thing out, and what they would do when the audience is there and the lights go on.

When did you start planning for The Last Waltz?

The idea came around probably in September [1976]. Then I needed to talk to everybody about it and it had to germinate. When I started thinking about it originally, that we were going to do this and who we were going to invite, we’d only talked about Bob Dylan and Ronnie Hawkins. Then there were other people who had been so supportive, and that we respected so much musically, that we said, “If we’re gonna invite them, we shouldn’t forget Eric [Clapton ].” Over the years I saw him a lot. The same thing with Van [Morrison]. And then there’s our countrymen (sic) from Canada, Joni [Mitchell] and Neil [Young]. The whole thing just snowballed. Then after I had an idea of the people we felt should be a part of this, I thought about the people who had been so influential, Muddy Waters and the Staple Singers. That’s one of the reasons we went back later with Marty [Scorsese], shooting on the MGM soundstages for three songs: “The Weight” with the Staples; “Evangeline” with Emmylou Harris; and “The Theme From The Last Waltz.”

Did you have discussions about specific production things, like not having a whole film of just close-ups or the camera fixed on the guitarist’s fingers?

We had conversations about the approach: what we didn’t like about things that had happened in the past. We wanted to do this in a much tastier fashion, in a classic fashion. Marty was so in tune with that. He said, “I worked on Woodstock, and that movie was about the audience. This movie is about the music. This is getting people together who will never be together in our lifetime and an event that will never happen again.” And he said, “I want to do this in a way that shows how much I care about what’s happening here, and how grateful I am to be part of this.” That’s where those choices were made. We talked about how it would be shot, where the cameras would be. He went over that because he’s a very generous artistic person, plus he wanted everybody to be on the same page so we were all in a position to do what we possibly could.

Obviously, you had interaction about repertoire with Dylan before the show.

Oh, for sure. We all tossed our thoughts into the hat and then we would try stuff, and if it felt right, then we just did it. It was one of those things like letting some higher power make the decision, because the proof was in the pudding. “Let’s play that song and see how it feels.” We would say, “That was fun. Let’s do that.” But Bob wanted to do stuff that was connected with our origins together, which is why we did “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” which we played back then, and “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Had Met),” and obviously “Hazel” and “Forever Young,” because we working together on [Dylan’s] Planet Waves [album]. So, it was trying to find a connection, and not just do something that had nothing to do with anything. We wanted it to have some thought. In mixing it up, we ran through a bunch of crazy ideas too. Like Bob said, “Should we do a Johnny Cash song?” He would start singing a Johnny song and we all knew it was never gonna fly, but it would be fun to play it. It was really like throwing things up in the air and seeing where they would fall. We knew we wanted to do “Forever Young,” because it connected to the occasion with all the people there and this generation and all of this stuff.

It’s still hard to comprehend that Dylan and your group were booed on the world tour of 1966.

There was a thing that happened between Bob and the Band when we played together; we would just go into a certain gear automatically. Whether we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger. It was like, “Just burn down the doors ’cause we’re coming through.” When we did the Dylan and the Band tour in ’74, we did a lot of the same things we did back in ’66, and the people’s response was, “This is the shit and I knew it all along.” It’s really a very interesting experiment to see, to go from something that people were so adamantly against—we didn’t change nothing—and the world revolved, and everybody came around and said, “This is brilliant.”

Muddy Waters in The Last Waltz was incredible. You captured something that people will never be able to physically see and experience again.

Now when I’m watching it, I’m also hearing the power of it. You look at him and say, “This guy…I don’t know what the Rolling Stones would have done, or if a lot of music would have existed, if it hadn’t been for this guy.” It is one of the high points for me in this [film]. He must have been about 65 or so [Ed. Note: Close, he was 63], he came out and he was the daddy of the whole Delta Blues scene, for sure, but such a gentleman. There’s a true master. Muddy Waters came out there between all of these people and rocked the very foundation of the place that night. Sometimes I had to just catch myself not to be standing there with my mouth open.

Related: An audience member revisits The Last Waltz

What was your first reaction on viewing the new cut of The Last Waltz and hearing the music on screen?

Well, it’s pretty extraordinary to be able to see this better than it’s ever been seen, and to hear it better than it’s ever been heard, and for it to be so much more encompassing. It really is such a different feeling from what it’s ever been, such a tremendous improvement.

Watch Muddy Waters sing “Mannish Boy” in The Last Waltz

Related: Our 2023 obituary of Robertson includes tributes from many fellow legends including Scorsese