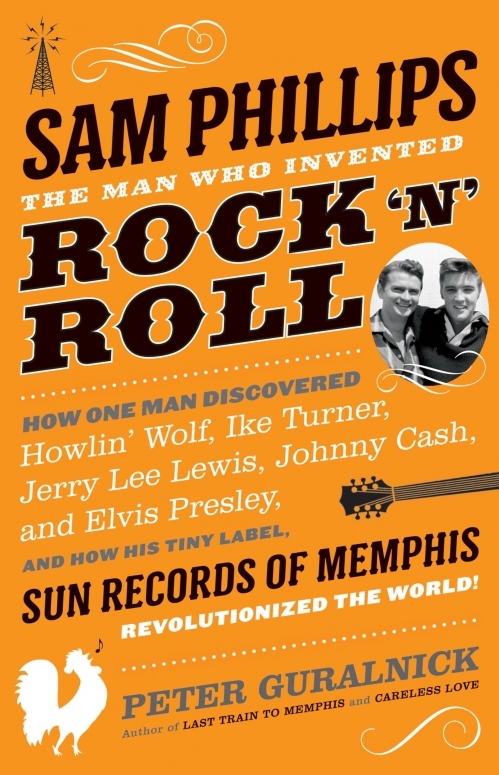

If his two-volume life of Elvis Presley, biography of Sam Cooke, Dream Boogie, and trilogy on southern roots music haven’t convinced you that Peter Guralnick is our finest chronicler of American music, his 2015 book, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll, should do the trick. A magisterial yet lively life of the founder of Sun Records, the label that arguably had a greater impact on what was heard in the latter half of the 20th Century than any other, it’s a book that places Guralnick in some pretty heady company. Arguably, he is to music what Robert Caro – author of The Power Broker and the five-volume life of LBJ – is to politics: a dogged researcher and graceful writer who has a genuine feel for his subjects and the knowledge to place them in a larger context. [Guralnick’s book is available to order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

If his two-volume life of Elvis Presley, biography of Sam Cooke, Dream Boogie, and trilogy on southern roots music haven’t convinced you that Peter Guralnick is our finest chronicler of American music, his 2015 book, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll, should do the trick. A magisterial yet lively life of the founder of Sun Records, the label that arguably had a greater impact on what was heard in the latter half of the 20th Century than any other, it’s a book that places Guralnick in some pretty heady company. Arguably, he is to music what Robert Caro – author of The Power Broker and the five-volume life of LBJ – is to politics: a dogged researcher and graceful writer who has a genuine feel for his subjects and the knowledge to place them in a larger context. [Guralnick’s book is available to order in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Phillips was born on January 5, 1923 and died at age 80 on July 30, 2003.

Guralnick, who was given a charge by his subject to “put it all in focus and filter out the bullshit,” succeeds admirably. He’s immensely helped by his subject, an indomitable, larger-than-life figure who was obsessed with sound (his first love was radio, and he was worked at or owned radio stations both before and after Sun) and his belief that “there was great art to be discovered in the experience of those who had been marginalized because of their race, the class, or their lack of a formal education.” It’s a wonderfully democratic vision for American music, and one that puts the contention by Phillips – whose views on race were very progressive given the time and place – that if he could find a white singer “with a negro feel,” he could make a million dollars into context. Or, as then-Billboard editor Paul Ackerman told him, “you’ve either got to be crazy or a genius” to release Elvis’ debut single.

It was a belief that led him to open the Memphis Recording Service, and brought him into contact with B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf (Phillips held the singer in great affection, and believed him to the the most profound performer he ever recorded), Ike Turner, and into business with the Bihari brothers, the shady owners of Modern Records, the perhaps shadier Don Robey of the Peacock and Duke labels, and the Chess brothers. These early forays into the music business don’t pan out financially, but they make for fascinating reading, as does Phillips’ messy and unconventional family life, where he remained married to his wife, Becky, while openly carrying on affairs, even setting up one mistress in the house next door, an arrangement that led to his often strained relationship with his sons, Knox and Jerry (but not so strained that they didn’t follow him into the family business).

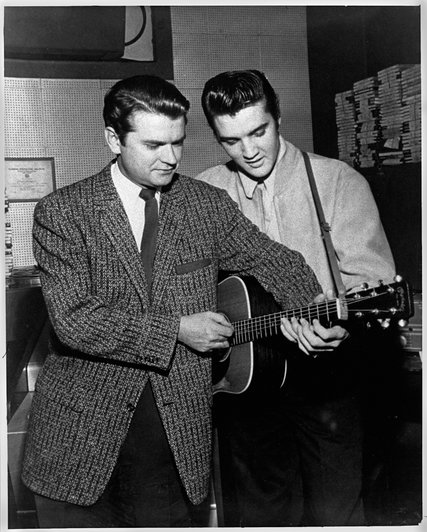

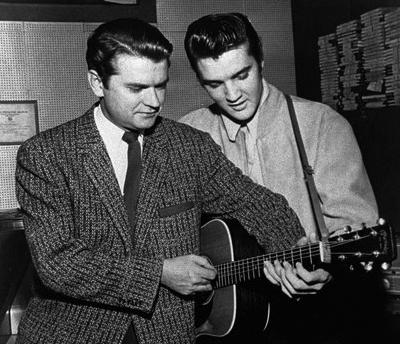

Guralnick is especially fine in documenting the work that went into the sessions, and how Phillips’ hands-off, let the performer find their own voice philosophy helped midwife some of the greatest music this country ever produced. A believer in in the perfect imperfection, he would record anyone who caught his interest, and had no problem keeping bad notes (Luther Perkins, whose deliberate picking was an integral part of Johnny Cash’s records, was barely able to play one note at a time), outside sounds, and even the musicians’ reactions (he talked Carl Perkins into keeping his enthusiastic “go, cat go!” in “Blue Suede Shoes”). And, of course, at Elvis’ first session, allowing Presley, Bill Black, and Scotty Moore time to run through nearly every song Elvis knew, until they hit on the magic of “That’s All Right.”

Related: Scotty Moore died in 2016

The story of Elvis and Sun has been told many times (including by Guralnick); the major points – Elvis showing up to record a song for his mother, Gladys, Jerry Lee Lewis and Phillips arguing over theology and “Great Balls of Fire,” the Million Dollar Quartet – are not ignored, but are shown to be very much of a piece. When “That’s All Right” becomes an immediate local sensation, Phillips doesn’t have time to bask in the glory: his first thought is that he needs to record a B-side. And the stories of Phillips driving through the south, trying to convince DJs and record stores to play and stock his discovery, only to be repeatedly discouraged, show the hard work behind the overnight success.

Related: Details of the “That’s All Right” recording session

And Phillips’ business dealings should resonate with independent labels and bands. One of the surprising aspects of the book is how briefly Sun was a going concern. It was barely a decade between Elvis’ first single in 1953 and 1962 when, stung by the decisions of Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash to leave Sun for major labels, he pulled back from everyday decision making, finally selling the label in 1970.

It’s a testament to Guralnick’s talent that he keeps your interest even when chronicling Phillips’ post-Sun career in radio. The sections devoted to studio designs and FCC licenses make more compelling reading than they have any right to be. But then Phillips was not a man who found success with WHER, featuring the first all-female on-air staff (when he recreated the format in Florida, the call-letters were WLIZ, in honor of Liz Taylor. The station’s slogan: You’ll Love LIZ, LIZ loves you”). It was also headquartered at one of the first Holiday Inns, and the relationship between Phillips and Kemmons Wilson, the motel chain’s founder, is one of the book’s many unexpected byways.

In addition to detailed and rounded portraits of Perkins, Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis, Guralnick populates the book with the eccentrics and castoffs Phillips collected. Dewey Phillips (no relation), the first DJ to play Elvis, Hank Williams’ widow Audrey, producer and musician Jack Clements, Billy Riley, and just about anyone who worked, recorded or just passed through 706 Union Street gets a vivid thumbnail bio.

He’s just as thorough when it comes to the music. To get an idea of how beautifully and economically he gets, he describes Jerry Lee Lewis’ “Great Balls of Fire,” as a “masterpiece, a song that in anyone else’s hands would have been little more than an exuberant novelty number but through the controlled application of energy and belief became a triumph of technique, an exquisitely etched miniature of epic proportions.”

Guralnick met Phillips in 1979, which leads Guralnick to an unexpected choice for Phillips’ final years: the book changes from a third-person, omniscient narrative, to Guralnick’s personal dealings with Phillips. This change of focal length is initially jarring, but eventually makes sense. By portraying the full force of Phillips personality first-hand, it gives a sense of the charm and energy that drove the man. It’s part of the warts and all history that Phillips demanded from Guralnick, and despite his own obvious personal affection for the Phillips, he admirably delivers.

It’s such a wonderfully nuanced and shaded portrait, that when you come to the end, you recall Paul Ackerman’s description of Phillips as being “either crazy or a genius,” and think, why not both?

To commemorate Sun’s 70th anniversary, in 2022, Guralnick published The Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Illustrated Story of Sun Records and the 70 Recordings That Changed the World.

- 10 Times the Beatles Used Pseudonyms on Records - 04/15/2024

- 10 Top Second Albums From Classic Rockers - 12/23/2023

- 10 Memorable Rock Concert Riots - 12/09/2023

2 Comments

Big Joe Turner invented Rock and Roll. I believe he had a patent.

I say “How High the Moon” was the first rock n roll tune. You had a sweet singer, and one of the baddest guitar players on the planet.

Give Ike and Jackie second place with Rocket 88. A song about an Oldsmobile can’t be number one.