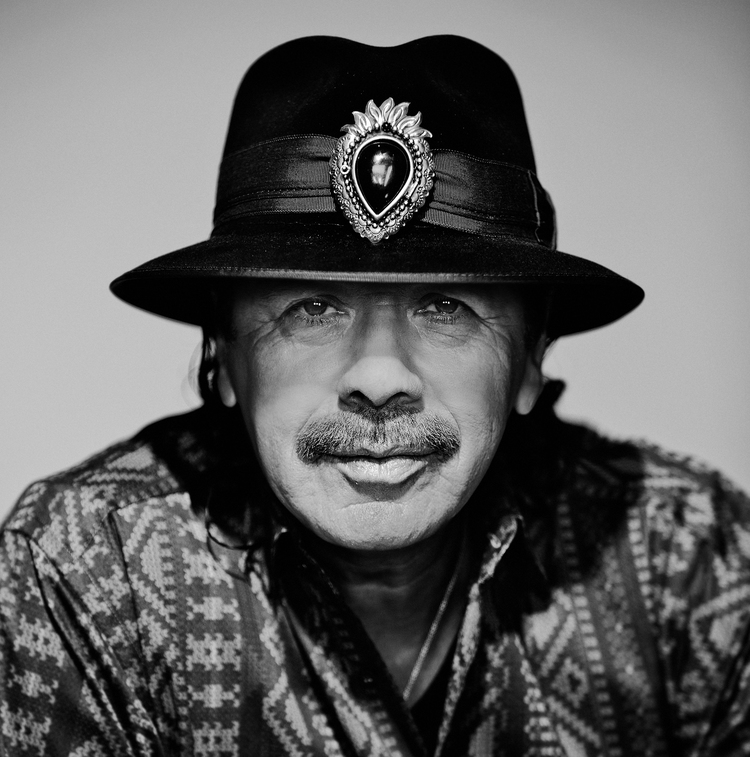

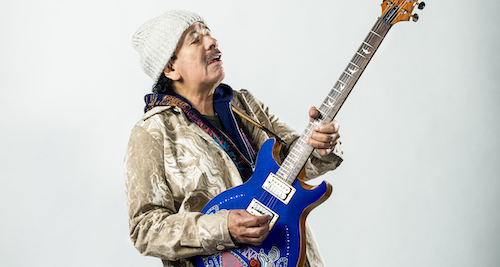

For more than five decades—from his earliest days as a groundbreaking Afro-Latin-blues-rock fusion guitarist—Carlos Santana has been the visionary force behind artistry that transcends musical genres and generational, cultural and geographical boundaries.

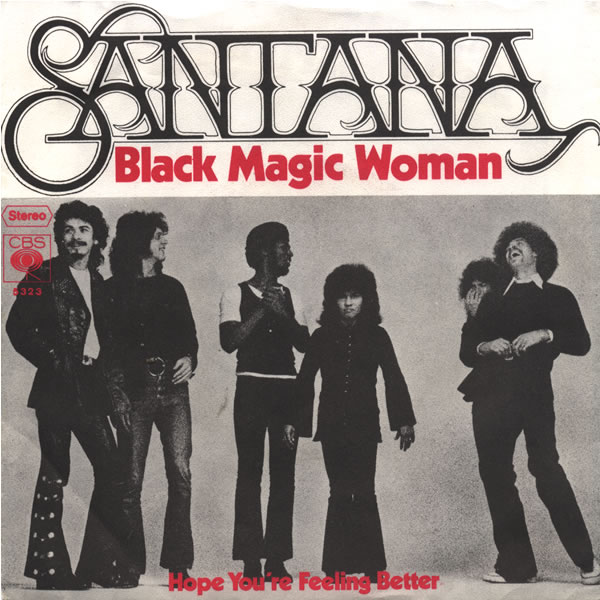

Santana arrived in the era-defining late 1960s San Francisco Bay Area music scene with historic shows at the Fillmore and other storied venues. The group emerged onto the global stage with an epic set at the Woodstock festival in 1969, the same year that its self-titled debut LP Santana came out. Introducing Santana’s first Top 10 hit, “Evil Ways,” the disc stayed on Billboard’s album chart for two years and was soon followed by two more classics—and Billboard #1 albums—Abraxas and Santana III.

More than 50 years and dozens of albums later, Santana has sold more than 100 million records and reached more than 100 million fans at concerts worldwide.

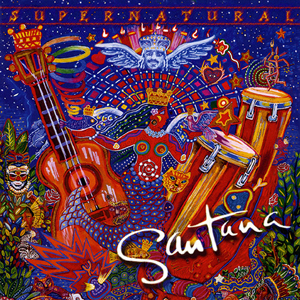

Santana has won 10 Grammy Awards, including a record-tying nine for a single project, 1999’s Supernatural (including Album of the Year and Record of the Year for “Smooth”) and three Latin Grammy Awards. In 1998, the group was ushered into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Among many other honors, Carlos Santana received Billboard Latin Music Awards’ 2009 Lifetime Achievement honor, and, he was bestowed Billboard’s Century Award in 1996.

On December 8, 2013, Carlos was the recipient of the 2013 Kennedy Center Honors Award.

The arc of Santana’s performing and recording career is complemented by a lifelong devotion to social activism and humanitarian causes. The Milagro Foundation, originally established by Carlos Santana and his family in 1998, has granted more than five million dollars to non-profit programs supporting underserved children and youth in the areas of arts, education and health. Milagro means “miracle,” and the image of children as divine miracles of light and hope—gifts to our lives—is the inspiration behind its name.

Carlos Santana was born in Mexico. He lives in Las Vegas, Nevada, with his wife, drummer Cindy Blackman Santana. Carlos turns 75 on July 20, 2022. He remains a top concert draw, but unfortunately, he collapsed onstage at a concert near Detroit on July 5, and was forced to subsequently postpone several shows.

This freewheeling Q&A is derived from interviews conducted in previous years.

Best Classic Bands: Let’s talk about the 1967 Summer of Love. You were just becoming known in the Bay Area and the Santana band had not yet formed. What do you remember most about it?

Best Classic Bands: Let’s talk about the 1967 Summer of Love. You were just becoming known in the Bay Area and the Santana band had not yet formed. What do you remember most about it?

Carlos Santana: The Summer of 1967 was about awakening. It was through music and doing what Jesus did at the mountain with bread and fish. It was gluten-free and mercury-free (laughs). San Francisco is very forward-thinking so lot of people from different parts of America hate San Francisco. We don’t like to follow in San Francisco. You see American Indians. African people. Young chicks (laughs). All together, man. Age don’t matter. Color don’t matter. Here’s the word: Consciousness revolution. It did not come from Liverpool or New York. I think it came from San Francisco. The psychedelic shock. Haight-Ashbury. When I first walked on it, I was like, “Man, this is like being inside one of Bob Dylan’s songs or something.” I’m very grateful that I was in San Francisco when it all hit: the Doors, Grateful Dead, Ravi Shankar, John Coltrane. There was an explosion of consciousness that made you question authority. Black power, rainbow power.

Related: Our Album Rewind review of Abraxas

I just didn’t like plastic flowers and phony people, I guess ’cause I was a hippie before I was a hippie. I didn’t want to be part of plastic Hollywood. I like Elvis when he was on Sun Records. I liked when he sounded like John Lee Hooker from Tupelo, Mississippi. That is relevant.

So, San Francisco was an affirmation to the rest of the nation: “We don’t want to be square. We don’t want to be sent to war for somebody to make profit and selling weapons.” They didn’t see the big picture. They call you “dirty hippie” and “unpatriotic, traitor.” No. I will defend this nation, especially against people within the nation who are trying to enslave us with the wrong doctrine.

In our music, before the [Columbia] record deal, 1967, [we were the] Santana Blues Band. The urgency was to realign ourselves with the American Indians, Geronimo, Apaches, Zapata, Che Guevara, Black Panthers. There’s a reason it’s called consciousness revolution. After a while, being with the hippies, there was some good stuff and some not so good stuff. Hip is Billie Holiday. Coltrane. Bob Marley. Square is a dumb-ass, self-centered, egotistical person who has no room for anyone else and themselves to admire. A hip person is all-embracing, all-encompassing for all people for the life of the planet. That’s hip! The squares are about you and your color. Or you and your scene. It’s self-centered, greedy, predictable and boring.

Watch Santana’s legendary performance of “Soul Sacrifice” at Woodstock

The only thing the Santana band never wanted to do was succumb to phony. We were watching what was unfolding with Sly Stone and Jim Morrison and it was becoming too much for all of them. [They were] becoming victims of an avalanche of illusion by not being prepared mentally to not deal with mass-quantity adulation. I’m not dependent or addicted to mass adulation. That stuff makes me feel uncomfortable. I’m not afraid of it. I have learned to balance it.

FM radio in 1967 blew my mind when I found it. They played the whole songs of Vanilla Fudge, Country Joe and the Fish, the long version of Traffic’s “Smiling Phases,” the long version of “Light My Fire.”

“Wow. This is really, really cool,” taking LSD and listening to Frank Zappa.

For me, being right out of high school, and listening, really listening, gave me a vast awareness of “Where do I belong in all this?” I looked at B.B. King on my left and Tito Puente on my right. And that was a peak on acid when I saw this. “You can do both. You can be both.”

Jerry Garcia. He didn’t assert or influence. To me there was either it’s black, it’s white or it’s grey. And he was like, “It’s all of them.” “What?!” I was very definable. I’m a thug, a punk from the [San Francisco] Mission District who is really over-opinionated about a lot of shit. I just didn’t know how to present it, even though my opinion was valid and what I want is valid.

You’ve written your autobiography, The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light. What did you want to say with it?

I wanted to share a story of how it can be done. I was at a picnic in San Jose many years ago. In one corner there was mariachi music and over at another place was Latin music, like Tito Puente, and another part was a band playing sort of blues, and I’m hearing the whole sound at the same time. “Yeah! OK. I get it.” Out of that picnic, I walked away with, my favorite word, “We can crystalize all that you can imagine.” I wanted to do songs that were slow and fast. God just gave me this mind.

I wanted to honor my mother. She’s the one who rescued me from myself many times. I was destined to be dead already or be in jail in Tijuana if I would have stayed there. But even in Tijuana, people offered me to play lead guitar rather than bass because they felt I had a feel for the guitar. The main thing is that I am grateful because out of a lot of people, I’m chosen to carry on a certain way of life, a certain way of manifesting music. A lot of people give me attention.

Your autobiography is candid and honest.

I got in trouble when I said there are only two kinds of people: artists and con artists. I really learned to balance, to take the high road. Look at the aerial view. See the big picture. Walk with grace and elegance.

Bill Graham, the late San Francisco concert promoter, is a recurring character in your book. He not only presented the band many times but also managed you for many years before his death in 1991.

Bill Graham is still present in my life every day. I make decisions thinking of him. I call it “putting on the Bill Graham hat.” I’m really grateful to him. I did learn not to say, “I’m just a guitar player and don’t have to think about that.” Copyrights, masters—that’s what I learned from Bill Graham: How to mind the store. Don’t look the other way. It’s your store. If you go broke, it’s your fault.

A big leap was made with Caravanserai, your fourth album, issued in October 1972. It was a big departure sound-wise from your first three LPs: lots of instrumentals and no hit singles.

There were also changes in band personnel. It was the last Santana album to spotlight Gregg Rolie and Neal Schon. The music shift really surprised a lot of people. “What are you doing? You’ve got the keys to every room.” Everybody thought we should just duplicate Abraxas over and over. And I said, “No. That was then. We need to move forward, even though it’s dangerous.”

Watch Santana’s 2016 reunion with Neal Schon and Gregg Rolie

After a while when the dust settled, it was just [drummer] Michael Shrieve and me. Because at the time, Gregg and Neal wanted to go a certain way and that [became] Journey. I didn’t want to go that way musically. With all respect to Journey, I want to hang out with people like [jazz saxophonist] Wayne Shorter and people to me who are like oceans. And I don’t want to be afraid of the wave.

Are you tough with the members of the band about how they conduct their lifestyles?

Are you tough with the members of the band about how they conduct their lifestyles?

No. If you want something, you don’t have to scream for it; all you have to do is long for it, like a baby crying for food. Someone comes to feed you. That’s how the musicians came to the band. They come to the band because they identify with the same thing that I need.

Related: Our interview with original Santana drummer Michael Shrieve

Do you think drug use harmed the original lineup?

I don’t think drugs, or, money, power or lust for women did it. I think what did it was lack of discipline, because all those things are steps. I’m not saying they are bad or good steps. You take them as they come, to get to a higher place. What destroyed the [classic ’60s lineup] was the main thing that destroyed the Beatles, lack of direction, lack of having a goal, lack of conviction. You all say, “Man, we’re gonna be the best. Set up a target.” And all you do is concentrate on it and get it. Once you hit that target, you have to get another target. That’s what mainly happened to the band. People started over-indulging on everything.

You are now financially secure. Coming from the barrio you must have been poor. Has the money ever been jolting?

You are now financially secure. Coming from the barrio you must have been poor. Has the money ever been jolting?

I remember poor adobe houses. I can’t remember ever being sad. I don’t think anyone denied me anything. The main thing is that I am grateful because out of a lot of people, I’m chosen to carry on a certain way of life, a certain way of manifesting music. A lot of people give me attention.

Watch Santana perform “Evil Ways” at Woodstock, in an outtake from the film

Tickets to see Santana perform are available here and here.

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

1 Comment

Above and beyond his music, Carlos is a very cool and unusual cat. I’ve heard things that he’s said at various times over his life and mine, and they’ve always made sense to me. So glad he’s still with us.