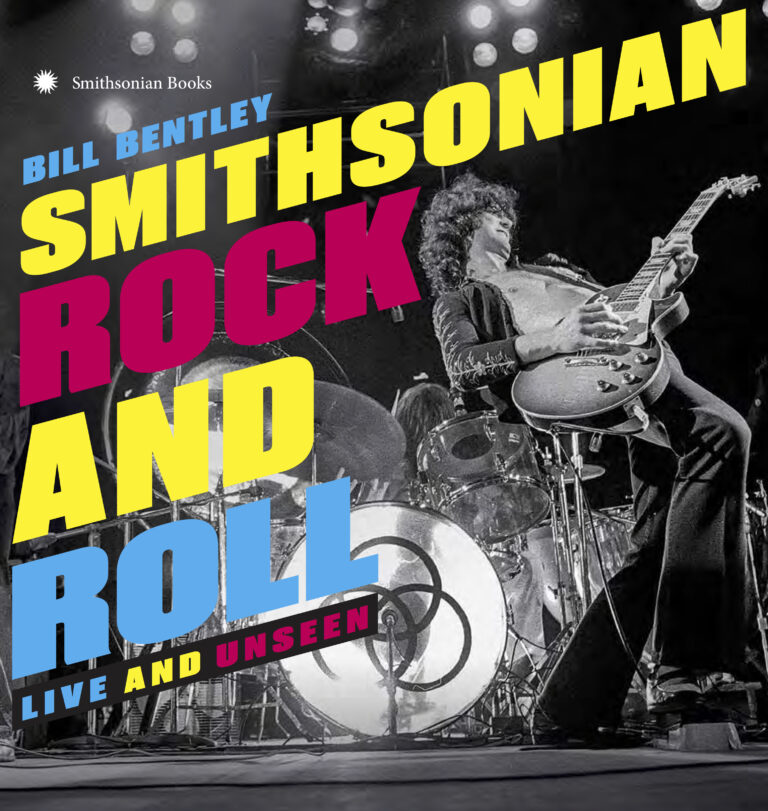

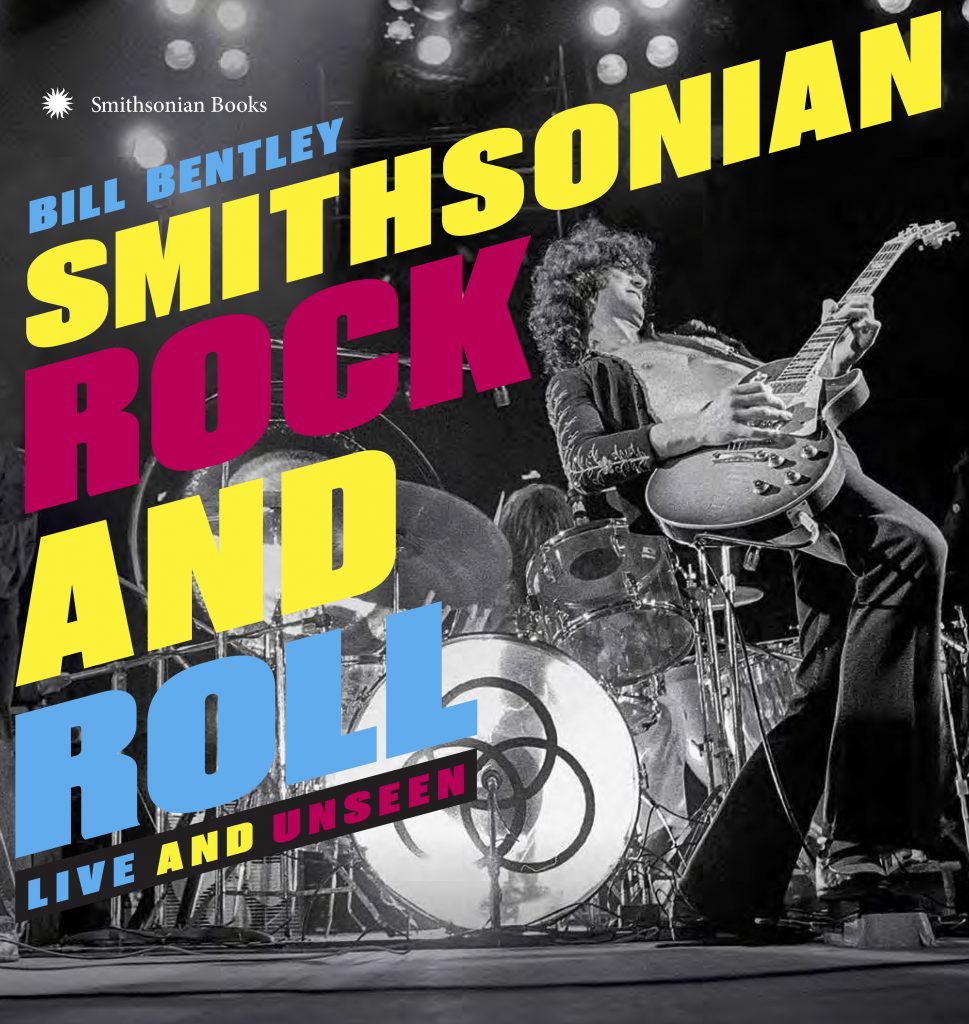

Smithsonian Rock and Roll: Live and Unseen is a recently published coffee-table book of mostly crowd-sourced rock ’n’ roll photography, showcasing unseen photographs from fans and music industry insiders. Published by Smithsonian Books, the volume features photos of many of rock’s most iconic artists through the ages, along with accompanying write-ups from music industry veteran Bill Bentley.

Smithsonian Rock and Roll: Live and Unseen is a recently published coffee-table book of mostly crowd-sourced rock ’n’ roll photography, showcasing unseen photographs from fans and music industry insiders. Published by Smithsonian Books, the volume features photos of many of rock’s most iconic artists through the ages, along with accompanying write-ups from music industry veteran Bill Bentley.

In total, the book features 142 artists spanning more than six decades of music history. Presented together, according to a press release, “These photographs create a kaleidoscopic history of the music, the concerts, and the fans. Smithsonian Rock and Roll is the perfect book for music lovers who want to see their favorite artists in new ways, both onstage and behind the scenes.” Order it here.

Best Classic Bands spoke with Bentley to find out the story behind Smithsonian Rock and Roll: Live and Unseen.

What was the genesis of the project?

Bill Bentley: The Smithsonian Books staff wanted to do a book celebrating rock ’n’ roll, but base it as much as possible on photographs taken by fans of the music over its entire history. So they put out a call on their website, which is one of the mostly heavily trafficked in the U.S., asking people to submit their photos. And once they started pouring in, we all knew we were on to something.

What is the Smithsonian’s interest in rock music?

The Smithsonian staff feels one of America’s most exciting and influential art forms has been music of all styles, with rock ’n’ roll being one of such pervasive impact. It truly speaks to all of America, so the Smithsonian Institution as a whole wanted to address the subject in a broad and hopefully democratic way.

How did the idea come up to solicit photos from fans as well as professional photographers, and what was that process like?

The original idea came from the head of the Smithsonian Books division; several staffers were massive rock ’n’ roll fans. The process was overwhelming once the photos started coming in. There were thousands and thousands, and more every day. Going through them once they’d all been collected, right up until the last day for submission, was daunting. You could feel the passion behind all the photos. People’s lives were defined by the images they’d taken and then felt strongly enough about to submit them. It was an emotional process trying to choose the ones that communicated the most emotional importance.

How many photos were received and how were they chosen?

Almost 5,000 photos were received, and several editors at Smithsonian Books, outside photo researcher Susan Brisk and I started going over them all at the start of 2016. It’s amazing how detailed it is to look at hundreds of photos a day, and then decide over a winnowing process of several months which might actually be included in the book.

How did you determine which artists were worthy of final inclusion? There were many that, of course, didn’t make it.

As in any historical overview, the ultimate deciding factor rests with the editors and writer, which would be me. We all wanted to include artists that made an impact in the music, whether it was by popularity or through influence. So it was a bit of a tightrope to finally pick who would be included. There were personal choices allowed, of course, and because of the actual pages that were going to be in the book, there were dozens and dozens of artists who we couldn’t include. But at the start of the discussions of those we had to leave out, I immediately started wishing for a Volume II sometime in the future to be published. Then maybe we can include bands like the Byrds, the Moody Blues, Radiohead and on and on. And definitely Moby Grape.

Can you talk a little about what you were seeking in the photos?

In choosing what photographs to use, I always wanted to feel a strong emotional and almost visceral reaction to the photos. I’ve been listening to rock ’n’ roll for over 60 years, since I was five years old, really, and I always get a physical sense of its power when I am listening to it, watching it live and even looking at photographs. It makes my heart beat faster and my skin start to tingle. That’s what I was looking for in the photographs we were able to use.

With few exceptions, the book covers the ’50s-early ’90s. Was there some editorializing as far as weighting the book toward certain periods of the music?

In discussing our final choices, we felt so much of what a book like this can convey is the early evolution of rock ’n’ roll, along with how it developed. Being someone who did witness its birth and evolution, so many of the early artists and then into the ’60s, ’70s and on into the ’90s made such an impact on what the music is now. And in five or 10 years we’ll be able to look at the 2000s with an overview that allows us to see who really made a difference during those years, and hopefully include them in my dreamed-about Volume II.

All artists are basically treated equally—one or two pages per artist and on to the next one.

All artists are basically treated equally—one or two pages per artist and on to the next one.

It was usually the quality of the photos that decided which artists got two pages. There had to be a visual reason that demanded they not be limited to one page. It was the hardest decision to make, actually, and likely some will question why some extremely important artists did not get a double-page spread. Like I said, it was mostly about either having or not having the kind of images needed to extend the coverage to two pages. Nobody’s perfect, and in hindsight I can see a few instances when one page just wasn’t enough to express how influential a particular artist has been to the evolution of rock & roll.

What were you looking to convey in your essays, which had to be necessarily brief? It was really hard to be succinct enough to say what needs to be said about a band like the Beatles in such a short space. So I really tried to aim my words at something less than an academic overview and hopefully try to capture the spirit of the artist in such a short space. It was almost like writing extended haikus, and my editor Raoul Hernandez, who I have worked with for almost 25 years as a contributor to the Austin Chronicle, was so good at bringing me back from going off the ledge and hopefully making the essays educational and entertaining at the same time.

Who is the target audience for the book?

I have always felt the target audience is those who totally love rock ’n’ roll, no matter what style or period, along with newcomers who want to see and read about over a 100 artists who helped create and then pave the way for the music to become the massive art form it is today. I have seen everyone from experts to neophytes look at the book and find something to like. Which makes me feel the amazing team of photographers, graphic designers and editors succeeded in our early mission: to make it fun to live with the book as a breathing thing.

While you were working on it was there a sense—because this has the Smithsonian imprint on it—that you had to make some kind of definitive statement about rock ’n’ roll?

I never felt like the book needed to be definitive, because at its very core rock ’n’ roll is all about personal passion. I tell people the music is meant to be loved, and there is no right or wrong about what you love. Love is an emotion that is unique to everyone who feels it. It’s not a competitive sport, or even a rational sport. Music is meant to move something deep down inside, and what does that for me might not do it for anyone else. Most important is to feel the spirit and let it take over. When that happens, freedom is found.

Anything else you’d like people to know about it?

I have always had the theory that we listen with our ears and our eyes. That’s why the live concert experience, which this book is based on, is such an integral part of music lovers’ lives. I’ve never met someone who only wants to listen to recorded music. They want to see it live too. It’s a bond between fans of rock ’n’ roll and blues and soul and country and jazz and any other style: sharing it with others, whether it’s in a juke joint in Mississippi or Shea Stadium in New York; it’s when levitation can occur. For me, that’s been the chase my whole live, and as they say, it’s too late to stop now.

Related: A book makes the case for 1971 as rock’s best year

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]

Listen to a Spotify playlist based on the book

Watch an interview with author Bill Bentley