If a young, unknown singer-songwriter left his small Southern town to try to break into the music business in New York City, you might expect him to at least consider the possibility that he’d be unsuccessful. But that thought apparently never entered Steve Forbert’s mind when, in 1976, at age 22 he packed up his Martin guitar and harmonica, said goodbye to his Meridian, Mississippi, hometown, and headed for the Big Apple.

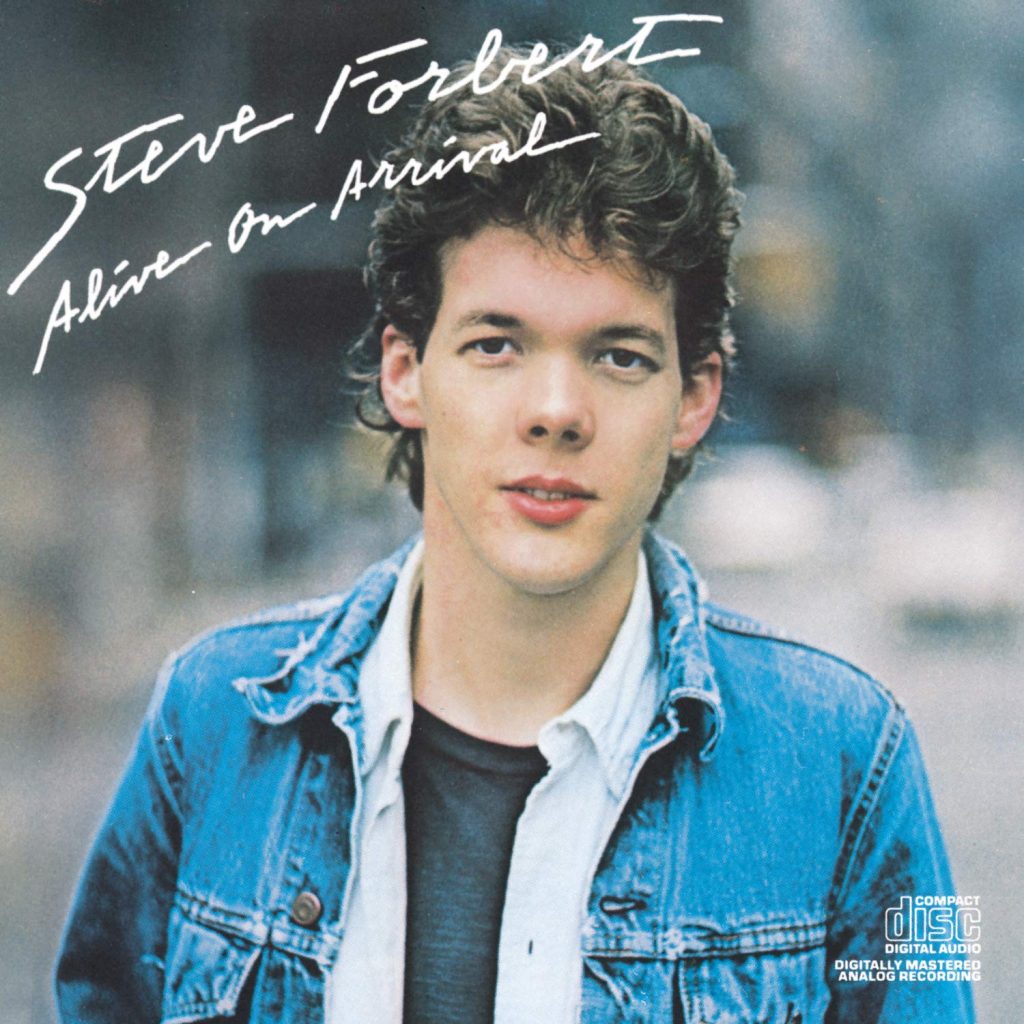

When he spoke with us in 2022 via Zoom from Asbury Park, New Jersey, where he now lives, we asked Forbert about a line in “Goin’ Down to Laurel,” the opening track on his 1977 first album, Alive on Arrival. In that tune, he proclaims that he’s “glad to take a chance and play against the odds.” Was that perhaps his feeling about making it as an artist in the highly competitive New York scene?

“No,” he told me. “I thought I was gonna get a record contract…I was pretty sure of that.”

Forbert’s comment may suggest naïveté or overconfidence—unless you’ve heard that debut album, which showcases a fully formed and considerable talent. It’s hard to imagine that any competent record company rep who heard the songs that later surfaced on that LP wouldn’t want to sign up that performer in a hurry. And sure enough, it didn’t take long for Forbert to secure his first contract, with the CBS-distributed Nemperor label, which released his first four records. The most successful of these was his sophomore recording, Jackrabbit Slim, which produced the pop hit that remains Forbert’s best-known song, “Romeo’s Tune.”

A dispute with Nemperor and other issues kept him from recording for six years in the ’80s, and there have been some relatively slow periods between then and now as well. But Forbert’s discography today includes nearly two dozen noteworthy studio albums, several live CDs and at least five compilations.

Though he says he hasn’t been as prolific in the last few years as he was in his 20s, Forbert, born Dec. 13, 1954, has lately given his fans a lot of music. The Magic Tree, for example, came out in 2018, followed by Early Morning Rain, a covers LP, in 2020, a year that also witnessed the appearance of Rodgers Revisited, a collection of live versions of songs by Jimmie Rodgers, one of Forbert’s heroes (and a fellow native of Meridian). Around the same time, he issued Jackrabbit Slim Live in Asbury Park, which features concert versions of all the songs from his second album. He has also released a memoir, Big City Cat: My Life in Folk-Pop, which came out in 2018. And now there’s a new studio CD filled with original material called Moving Through America.

We talked about that album and a lot more during our Zoom call. A lightly edited transcript follows, along with a video that includes portions of the text below and other material as well.

*****

There was a lot of youthful exuberance in your early songs. You even sang “I’m glad to be so young.” And you were young—about 23 when you recorded that first album. Now you’re 67.

There was a lot of youthful exuberance in your early songs. You even sang “I’m glad to be so young.” And you were young—about 23 when you recorded that first album. Now you’re 67.

Who told you all this? [Laughs.]

You can find out a lot on the internet. How has age changed your songwriting? Do you think there are songs you wrote then that you couldn’t write now?

There are definitely songs I wrote then that I couldn’t write now. If you listen to the new record, you see a lot of character portraits on there. Not as many personal experiences as on those earlier records. Because as you get older, you’re not out on the scene scuffling or getting thrown out of bars. And a lot of what was once new and exciting…you’ve been through it about five times. And then as you get older, you hopefully are playing it a little safer, and not “glad to be so crazy in my day” [a line from “Goin’ Down to Laurel”], and you might want to express yourself through things you see around you since you’re not out raising as much hell as you used to 40 years ago.

One of the songs I like best on the Jackrabbit Slim album is “January 23-30, 1978,” which includes one of my favorite lines: “It’s often said that life is strange/Oh yes, but compared to what?” That song sure sounds autobiographical. Is it?

Totally. Everything in there is an account of a trip back home to Meridian between January 23 through 30, ’78.

You had a slow period after the first few albums and I’ve heard you say that that was your own fault, that you lost touch with what it was all about. Can you explain what you meant?

I just felt like I had to put out a record every year. That was sort of the norm back then and that’s what I was expecting to do. I would have liked to have taken a little more time to look at the situation and say [to myself], for example, “You’ve got several outtakes from Alive on Arrival and several outtakes from Jackrabbit that you’re happy with. Why not put out a record after Jackrabbit with those and let people hear those songs while there’s a lot of interest?” Those sorts of thoughts. I was just in too big a hurry to think things like that. I wasn’t drinking so much that I lost all my teeth, like maybe some well-known guitarist you might have heard of, but I was in a little bit of a whirlwind from it all.

If you were trying to describe your music to someone who’d never heard it, what would you say?

Singer-songwriter stuff. [Laughs.]

That’s pretty vague. What’s different about Steve Forbert?

Well, it’s certainly personable stuff. It’s not presented to be loud music. I’m coming from telling stories quite often, and it’s folk-rock. It’s called Americana now, but that’s OK with me. When I started, that term wasn’t around.

Watch the author’s interview with Steve Forbert

How does a song come together for you? Do you take notes about your experiences when you’re traveling? When something catches your eye, how does it turn into a lyric and a melody?

Well, you just save these things that appeal to you. It may be years before they develop a context to be presented in. For example, on the new record, “It’s Too Bad (You Super Freak),” I’m standing outside of a hospital stomping out a cigarette. There’s irony in that to me, and I had jotted that down and it stayed with me for a while, and then I just wrote a song. So, you make use of these phrases that you think are worth singing to people. Sometimes the songs come to you on the spot, and you write them down, and sometimes you save [the phrases] for a while.

You’ve mostly worked with a producer rather than self-producing. How have producers helped you?

Almost all the ones I’ve worked with helped me a lot. There’s a whole world of stuff in the craft of making records that’s just not something I have time for. I’m not a recording engineer. And it’s good to have another opinion. There are so many decisions to make. I know what the songs are; I know when they’re finished. I’m not looking for a lot of input on those, but making records involves a lot and I don’t do a lot of technical stuff with equipment and all that. It’s not a passion of mine.

Did you approach this new project, Moving Through America, from a particular musical mindset or with a particular goal? Or is this just your latest batch of songs?

Did you approach this new project, Moving Through America, from a particular musical mindset or with a particular goal? Or is this just your latest batch of songs?

Well, I made the covers record [Early Morning Rain] with Steve Greenwell. He had mixed a previous record with me called Compromised [2015], and I liked his sonic skills. I liked working with him. So, we were able to work on the covers record and finish it here in Asbury Park, and then I just kept going. This freaking virus thing hit, but we were able to keep recording. So that’s what Moving Through America is. We just kept going from the covers record into the new one with these original songs. We used the same players.

The title cut on Moving Through America is a new version of a song that was on The Magic Tree. And that album’s title cut appeared in two versions on that CD. What makes you decide to re-record something?

Yeah, “Moving Through America” was just a vocal and guitar on Magic Tree. I had tried that song back then, and I just thought the studio recording was way too bombastic. The only way it really appealed to me then was to just present it as a vocal and guitar thing. But as these couple of years went by, I kept performing the song live and I wanted to hear it with the whole combo production.

“Fried Oysters” is one of my favorite songs on the new album. You’ve said that’s about a guy waiting for his girlfriend to go to a restaurant. Are you that guy, or is it someone you know, or did you make it up?

Well, I could be that guy. I’m not the guy who’s got a gambling problem and heading back to Atlantic City, fortunately, like the guy in “It’s Too Bad (You Super Freak),” and I’m not the guy who’s out of jail and out on the street in that song “Living the Dream” [two other songs on the new album]. But yeah, “Fried Oysters” is closest to reality.

You don’t write much topical material, but there is some on this new album, “Buffalo Nickel” and “Please Don’t Eat the Daisies.” Do you pay a lot of attention to the news? Have you ever been tempted to perform for a political candidate? And how do you feel about musicians taking political stands?

You don’t write much topical material, but there is some on this new album, “Buffalo Nickel” and “Please Don’t Eat the Daisies.” Do you pay a lot of attention to the news? Have you ever been tempted to perform for a political candidate? And how do you feel about musicians taking political stands?

It’s not something that bothers me if a person feels strongly about something. It’s still a matter of the song. Just because the message may be right or for a worthy cause doesn’t mean that I want to hear the song 15 times. I’m interested in the song and making a good record of it that you want to live with and play over and over. I’ve never been inclined to back a political candidate.

Is that just a personal decision or do you feel musicians shouldn’t use their positions to do that?

You know, they can do whatever they want if they feel strongly about it. That’s fine. I find things to be very complex and so it’s a little hard for me to just rah, rah, rah about a particular political person.

I read an interview where you said the health scare you had [which included a cancer diagnosis] didn’t change you, that you just tried to sweep it under the rug and in fact were more focused on raising a kitten.

Yeah. [Laughs.]

But I find it hard to believe that a reminder of mortality wouldn’t have some impact.

It’s not over. There are still some complications. I’m not just tiptoeing through the tulips anymore, but I tried to do that.

Your memoir had a lot about the ups and downs of your career but compared with, say, Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography, it had relatively little about personal life—childhood, parents, reasons for drinking problems. Is that stuff you just don’t like to discuss, which is fine, or did it simply not happen to make it into the memoir?

Yeah, I just don’t like to discuss it.

Writing about the songs on this new album, you said, “You probably think the subject matter sounds pretty bleak, but nevertheless it’s one of the most musically entertaining albums I’ve ever released.” It occurs to me that that’s probably because even your relatively melancholy songs tend to be melodic and at least midtempo. “Times Like These,” about the homeless person, has a bouncy melody that has me tapping my foot, for example.

Yeah, I want that to happen. Like I said, I try to make records that you’ll want to play again and again, and I hate to get too cliched, but you know, a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. I wouldn’t want to do a song about global warming and climate change and just bum you out. Just watch the news—they can do that for you. That’s not what you’re gonna look to me for. I try to make it a really good song that I’m gonna play live and have fun playing. You know, I wonder how often Leonard Cohen performed “Dress Rehearsal Rag.” Probably never. [Cohen did say in a 1992 interview that, “I would never do that song in concert,” though he has performed it live at least once.]

A few years ago, you recorded Rodgers Revisited.

That was a labor of love, having done Jimmie Rodgers’ songs in my shows, a couple every night, I just compiled some of the better versions through the decades.

You’ve said Rodgers was heroic because he kept working through tuberculosis, but what is it about his music that’s so special to you?

Rodgers was a genius. They call him the Father of Country Music but there’s a certain elemental truth to Jimmie Rodgers as a recording artist. You can learn a lot about the way life really is by listening to him. He didn’t sugarcoat things. He put a lot of things out there that were the way they really were. And he knew a lot. If you really want to get serious about it, you can even go as far as “Whippin’ That Old TB,” a song he wrote. It’s almost at times dark humor about the fact that he was dying of tuberculosis. He’s a fascinating recording artist—although he barely made the cut. I mean, he’s one of the first. If he’d been born 15 years earlier, he might not have been a recording artist.

Related: Our review of Rodgers Revisited

Some of your stuff reminds me of Woody Guthrie. Would you consider him an influence, too?

Absolutely. I liked Woody Guthrie and I studied him and listened to Library of Congress records to see what all the commotion was about. And I read his books.

How about Jesse Winchester, who grew up not far from you in northern Mississippi. Were you a fan?

Yeah. That first record he released is the one I picked up on. Everything just came together for him. With Robbie Robertson at the helm, there was a lot of interest in him. There was a lot of light on that record. I bought it and I liked it a lot.

You started at a very different time in the music business. Do you think your career would be different if you were beginning now?

Well, I’m a song guy. If I were the same guy starting now—which is impossible, you’re a product of your time—but this thing now wouldn’t interest me much really. Everything’s been done. There are still probably a few really good songs out there to be written but there are so many songs now that people have access to home studios and posting things and Facebook pages and Instagram and all. Songs are not even a dime a dozen now. I think they’re 20 for a dime. Maybe 30 for a dime.

And people don’t listen to albums anymore; they listen to individual songs.

OK, the individual song can speak for itself. Most people only know “Romeo’s Tune” [from my discography], and I’ve written hundreds of songs, so I can’t complain about that. But I don’t think there’s as much accent as there should be on living the songs and writing songs that hopefully will stand on their own beyond your recording of it. Anybody can write a song, and anybody can now record that song. That doesn’t prove a lot.

I’ve heard you talk about some of the people who were coming up when you were—people like Sammy Walker, Tom Pacheco, Elliott Murphy and Bruce Springsteen. Why do you think some very talented artists like these make it big, others make it not so big, and others don’t make it at all?

There’s certainly an element of luck in it. After that I’d say, you look at the ones that are the best known and, by and large, they’re pretty freakin’ smart. It’s amazing how smart Beatle Paul has turned out to be. It’s amazing how smart Paul Simon is. I mean, he could have done anything. So that’s a factor. And you’ve got to have a really good manager, and you’ve got to really want to be super famous. If that’s your top priority, you’ll probably achieve it, but maybe some of the people you mentioned didn’t really want that. They didn’t really want to get out of a limousine and be bombarded with people accosting them while they tried to get into the Four Seasons hotel or whatever.

I’m guessing that wasn’t your top priority.

I don’t give a flip about that stuff. It’s annoying.

Watch a full hour-long concert by Forbert from 1979

Tickets to see Steve Forbert in concert are available here and here.

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]