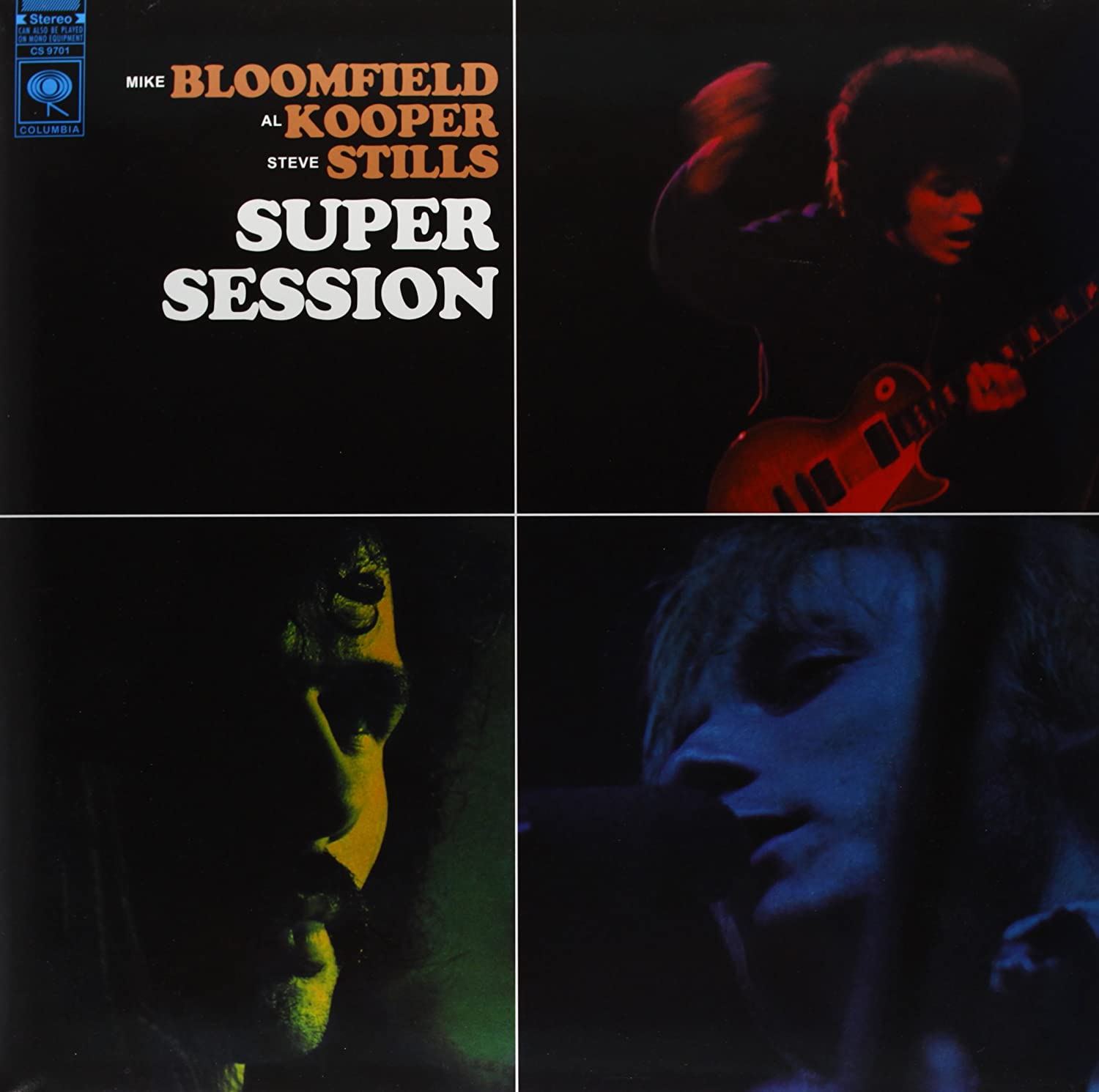

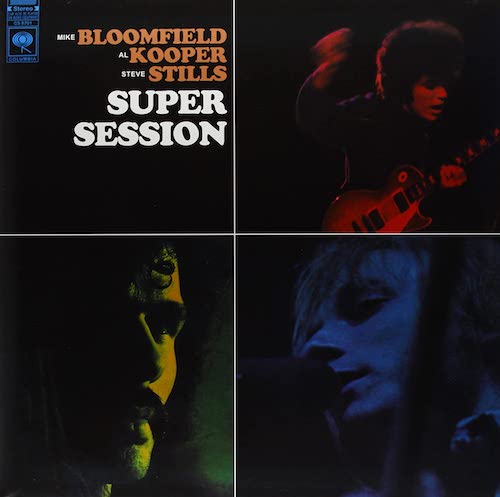

The funny thing about Super Session, the 1968 album put together by keyboardist/singer Al Kooper, featuring guitarist Mike Bloomfield on its first side and Stephen Stills on its second, is that it was such a huge success, going gold and making it well into the top 20. Funny because, Kooper once said in an interview with a publication called Bloomfield Notes, “That was the last thing on our minds, that that was going to be a successful record. I was trying to emulate the Blue Note jazz records of the ’50s in concept,” he said, “put a bunch of guys that can really play in a room and let ’em jam. Make rock ’n’ roll more of an art form, comparing it to those jazz records. And it turned out to be the most successful record of our careers.”

The funny thing about Super Session, the 1968 album put together by keyboardist/singer Al Kooper, featuring guitarist Mike Bloomfield on its first side and Stephen Stills on its second, is that it was such a huge success, going gold and making it well into the top 20. Funny because, Kooper once said in an interview with a publication called Bloomfield Notes, “That was the last thing on our minds, that that was going to be a successful record. I was trying to emulate the Blue Note jazz records of the ’50s in concept,” he said, “put a bunch of guys that can really play in a room and let ’em jam. Make rock ’n’ roll more of an art form, comparing it to those jazz records. And it turned out to be the most successful record of our careers.”

Kooper shouldn’t have been surprised, because Super Session was an album whose timing was perfect. The three principal players—who were augmented in the studio by bassist Harvey Brooks, drummer Eddie Hoh and second keyboardist Barry Goldberg (the latter on a couple of tracks), as well as a horn section arranged by Joe Scott—were all budding rock heroes. Kooper had only recently been ousted by the jazz-rock aggregation he’d created, Blood, Sweat and Tears, which admittedly went on to much greater fame without him. Bloomfield had exited the Electric Flag, the project he’d assembled after leaving the revered Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Stills had been a core member of Buffalo Springfield, another great band that had fallen apart—he’d find a cozy outlet for his music soon enough with friends Graham Nash and David Crosby.

Listen to “Season of the Witch” from Super Session

The idea of a “super session” was itself new in rock. In the 1960s, rock musicians belonged to a band; members might come and go but players from different bands rarely moonlighted or got together with cats from other bands informally, just for the sheer pleasure of it. If you happened to be in between bands, your goal was to find another group asap—that’s how you made your living. Perhaps a handful of admirers might meet up in a late-night club in New York or California for kicks, play some tunes for a few hours and then go back to their bands, but the concept of making an album, spontaneously, with a handful of peers was, at that point in time, nearly unheard of.

In retrospect, however, perhaps Super Session was more inevitable than not. Kooper, a New Yorker, and the Chicago-bred Bloomfield had been living virtually parallel lives since they’d first met up at the New York recording session for Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” on June 16, 1965. Kooper, primarily a guitarist at the time, had been invited by producer Tom Wilson to watch the proceedings, but, as he once told this author, “There was no way in hell I was going to visit a Bob Dylan session and just sit there like some reporter. I resolved that not only was I going to go to that session, I was going to play on it.”

Kooper brought his guitar with him, but once inside the studio he laid eyes on Bloomfield for the first time—and heard what the frizzy-haired marvel could do with a guitar. “I was in over my head,” Kooper later admitted. “I anonymously unplugged, packed up, and did my best to look like a reporter.”

Kooper, then 21, caught a break during the session when keyboardist Paul Griffin moved from the Hammond B-3 organ to the piano. As Wilson left the room for a while, Kooper saw his chance and took it. He’d never played a Hammond in his life, and later remarked that had Griffin not left the instrument on, he wouldn’t have known how to fire it up. Kooper snuck over to the keyboard and began improvising an organ line. To his surprise and delight, Dylan liked what he heard and told him to stay. “There is no music to read. The song is over five minutes long. The band is so loud that I can’t even hear the organ, and I’m not familiar with the instrument to begin with,” Kooper later wrote. “But the tape is going, and that is Bob fucking Dylan over there singing, so this had better be me sitting here playing something.”

Kooper’s keyboard and Bloomfield’s guitar became signatures that helped lift “Like a Rolling Stone” to the #2 position in the chart and to rock immortality—it’s often listed as the greatest, and most important, rock song of all time. Dylan invited both Kooper and Bloomfield back for the sessions that would become the album Highway 61 Revisited.

By 1966, both musicians were riding high—Bloomfield was doing spectacular, revolutionary work with the Butterfield Band on their East-West album while Kooper was creating similar miracles with the Blues Project, whose best album, Projections, was released around the same time. They’d both garnered a fan base among young rock connoisseurs who valued the higher level of musicality they trafficked in.

But by ’67, they were both gone from those bands: At the Monterey Pop Festival that June, Kooper performed solo (the Blues Project took the stage without him) while Bloomfield debuted his Electric Flag to rapturous approval. A few months later, Kooper formed Blood, Sweat and Tears and began work on their debut album, Child is Father to the Man.

Related: Our Album Rewind review of BS&T’s Child is Father to the Man

Then…you guessed it: By the following spring they were both out of work again. That’s when Kooper—who’d begun serving as an A&R (artists and repertoire) man for the label that had signed him, Columbia Records—got his brainstorm. He called Bloomfield.

“It was really a fated thing,” Kooper told this writer in an interview in the ’90s. “We had so much in common that we had to do something together. So many similarities. We had both played on the Dylan sessions and we were friends through the Butterfield and Flag period. We were both approximately the same age, we were both Jewish, we both loved blues, we both were in blues bands that we left to form horn bands. We were both thrown out of the horn bands that we formed and then there we were. There was a real genuine affection for each other. So when I started working as an A&R man at CBS, I called him and said, ‘Let’s make a jam session album,’ and he was into it.”

In the studio, the makeshift group recorded a few original tunes (“Albert’s Shuffle,” in honor of Bloomfield’s then-manager, Albert Grossman; “His Holy Modal Majesty” and “Really”) and a couple of covers (Jerry Ragovoy and Mort Shuman’s “Stop,” which had been recorded by soul singer Howard Tate, and Curtis Mayfield’s “Man’s Temptation”), and retired for the evening satisfied and eager to finish it up.

Listen to “His Holy Modal Majesty”

Listen to “Really”

The next day, Kooper awoke to find that Bloomfield had gone home. That’s how side two of Super Session came to be a Kooper-Stephen Stills collaboration. (Stills was actually billed as “Steve” Stills on the album cover; he has subsequently always used the full name Stephen.)

Listen to “Man’s Temptation”

“Bloomfield split in the middle of the night,” Kooper told this writer. “He left a note that said, ‘Couldn’t sleep, bye.’ So I called every guitar player I knew in Los Angeles and San Francisco: Jerry Garcia, Randy California, Steve Stills and I don’t even remember who else. Stills was the one who got it together.”

Listen to “Stop”

Needless to say, they had no material worked up. “We had nothing. I would’ve preferred that he sang because he was a better singer than I was but the problem was that he was signed to Atlantic,” remembered Kooper. “And as a producer I was worried about getting the rights for him to just play on it because we hadn’t talked to anybody about that. That’s actually how Atlantic got Graham Nash [who was signed to Epic with the Hollies at the time]. They swapped Steve Stills for Graham Nash. They gave CBS Steve Stills for Super Session and they got Graham Nash for CSN.”

Stills lent his guitar to covers of Dylan’s “It Takes a Lot To Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” an 11-minute jam on Donovan’s “Season of the Witch,” which became the album’s most talked-about track, and a Willie Cobb blues, “You Don’t Love Me.”

Listen to “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”

They rounded out the album with Harvey Brooks’ own “Harvey’s Tune.” (Kooper, incidentally, has stated that he absolutely despises the version of “Season of the Witch” that’s on the album. “I wouldn’t play that song if it was my dying mother’s last request,” he once told a reporter.)

Listen to “Harvey’s Tune”

Released in July 1968, the album eventually made its way to #12 and was eventually certified Gold by the RIAA on Nov. 4, 1970. It remains the best-selling album with which Kooper has been involved as a principal artist (and likely Bloomfield as well). It also led the way to a spate of like-minded “jam” albums, both from the principals involved (The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper) and seemingly countless other musicians.

“Super Session was a groundbreaking record in that it was the first real rock ’n’ roll jam session,” said Kooper in his interview with this writer. “I got the idea from [Moby Grape’s] Grape Jam album, which was really the first one. But that wasn’t really structured, it just kind of happened. Super Session was structured. Of course, there had been jazz albums where this was done, but I was really interested in trying to do it with rock ’n’ roll.”

Listen to “You Don’t Love Me”

While Bloomfield reportedly soured on his work on Super Session after it became an unexpected commercial sensation, reviews were generally kind, and it has persevered as a landmark of its era. Super Session has been reissued a number of times in various formats. The 2003 compact disc edition adds on four bonus tracks: The first two, “Albert’s Shuffle” and “Season of the Witch,” are remixes from the original session sans horns. “Blues for Nothing” is a Kooper-penned outtake from the session, and “Fat Grey Cloud” is a Bloomfield-Kooper live jam recorded at the Fillmore West in San Francisco in 1968.

Listen to “Albert’s Shuffle” without horns

Kooper, as of this writing, is in his late 70s and semi-retired, although he still surfaces for the occasional live gig and was releasing new music up until 2008. His career as a solo performer, producer, sideman and A&R executive continued to expand well after the Super Session era—he most famously discovered and produced Lynyrd Skynyrd. Bloomfield maintained a lower-key career after the ’60s, playing in various bands, often in small venues. Sadly, he died in 1981 under mysterious circumstances. He was only 37. Said Kooper, summing him up, “He was a very special guy.”

Listen to “Season of the Witch” minus horns

Listen to the bonus track “Fat Grey Cloud”

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

17 Comments

“Albert’s Shuffle” was not dedicated to Albert King, but rather to Albert Grossman, Bloomfield’s manager at the time and who had fronted him and the Electric Flag large $ums to keep the band afloat.

Thanks for that–we’ve made the correction.

For me the ultimate album fell asleep to it throughout my life went through 3 albums and 2cds would love to be able to play stop on my guitar follow up live adventures is a great double album

as is the Kooper/Bloomfield cd Fillmore East; The Lost Concert Tapes 12/13/68

Harvey’s Tune is a classic, love it 🙂

I agree that Harvey’s Tune is marvelous. I listen to it over and over again. But did it even exist before the horn arrangements were added later?

“…It remains the best-selling album with which Kooper has been involved…”. Has it really sold more than “Bringing it all Back Home”, “Highway 61 Revisited”, and “Blond on Blond”?

We meant as a principal artist, not as a sideman. We’ll clarify that in the article.

Listen to Kooper’s last couple solo albums – White Chocolate and Black Coffee. Excellent stuff

It was Bloomfield, not Kooper, who hated Season of the Witch.

I wonder why it’s never mentioned that Super Session was originally a Kooper/ Bloom project, but Bloomfield, was a hard core Speed addict who would go long periods of time without sleep many times collapsing during both live and studio performances. In the case of Super session, his collapse necessitated Kooper to find someone for a side two, Stephen stills ended up being in the studio, and was willing to finish the project for Bloomfield.

It would be cool if you would mention Kooper’s discovery and work with Shuggie Otis. (And btw, one was a nobody in my high school if you didn’t have a copy of “Projections”.)

Kooper wrote one of the greatest biographies (rock or otherwise). The brutally honest and incredibly enlightening “Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards”. Get the latest printing. It’s to his credit and strength of will that he persevered despite having the same manager as Badfinger.

I’ve read a lot of rock biographies, but I think Kooper’s is quite possibly the best. I’ve read it three times over the years!

I had both the album and the CD of the original recordings. I prefer the 2002 re-release with the horns stripped out. Bloomfield died of a heroin overdose. Can you expand on what was ‘mysterious’ about his death?

There are numerous theories about the CBS/Atlantic swap that allowed CSN to form. When I worked for the Warner Music Group, I was always told that Atlantic let Delaney & Bonnie go to CBS in exchange for Nash.

God how do I love those albums!!!!!!!!!! I used to listen to them over and over. I know every note and every lyric. I’m going right now to put Super Session on my CD player. Thanks.