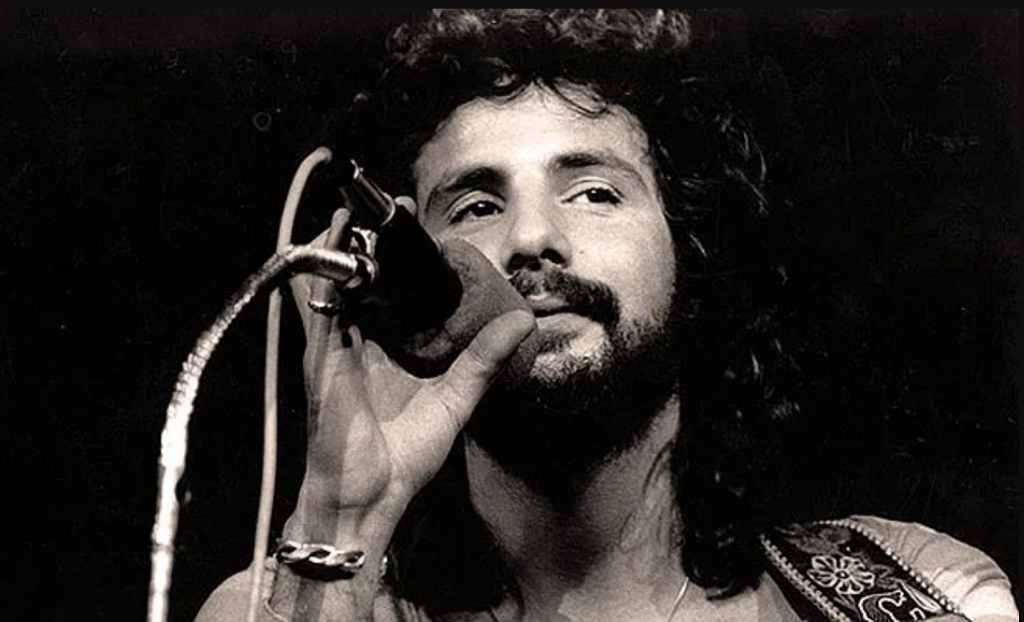

Despite his success on the pop charts of the 1960s in his native England with original songs including “Matthew and Son” and “I Love My Dog,” Cat Stevens (born Steven Demetre Georgiou on July 21, 1948) found himself questioning his musical career while hospitalized for tuberculosis in 1969. He’d not only become a potent stage performer himself, touring with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Engelbert Humperdinck, but a sensitive songwriter who supplied hits to other artists, such as the Tremeloes’ “Here Comes My Baby” and P.P. Arnold’s “The First Cut Is the Deepest.”

Despite his success on the pop charts of the 1960s in his native England with original songs including “Matthew and Son” and “I Love My Dog,” Cat Stevens (born Steven Demetre Georgiou on July 21, 1948) found himself questioning his musical career while hospitalized for tuberculosis in 1969. He’d not only become a potent stage performer himself, touring with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Engelbert Humperdinck, but a sensitive songwriter who supplied hits to other artists, such as the Tremeloes’ “Here Comes My Baby” and P.P. Arnold’s “The First Cut Is the Deepest.”

In the British Isles he was viewed as a “teen idol,” with regular appearances on Top Of the Pops. “To go from the show business environment and find you are in hospital, getting injections day in and day out, and people around you are dying, it certainly changes your perspective,” he later said. “I got down to thinking about myself. It seemed almost as if I had my eyes shut.” Finally recovered during a year of convalescence, he was meditating and doing yoga; his spiritual investigations informed the dozens of new songs that flowed. Stevens left his label Deram for the more artist-friendly Island Records (licensed to A&M in the U.S.), and enlisted ex-Yardbirds bassist Paul Samwell-Smith to produce his recordings.

Mona Bone Jakon and Tea for the Tillerman (released a mere six months apart in 1970) placed him firmly in the burgeoning and lucrative “singer-songwriter” category along with the likes of James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne, Carole King and Neil Young. Pop radio and the Billboard charts somewhat unexpectedly made ample room for confessional, quieter, acoustic-based music for the first time since the “folk scare” a decade earlier. It was a time when large arenas could host a solo performer one night, and the thunder of Led Zeppelin or Emerson, Lake and Palmer the next.

Review: For the album that became Teaser and the Firecat, Stevens demoed tunes in February 1971 and recorded final versions at Morgan Recording Studios and Island Basing Street in March. (He was also working on a children’s book of the same name, which he wrote and illustrated, publishing it in 1972.) Much of the album consisted of small-group “live in the studio” takes, with minimal overdubbed percussion, keyboards or vocals. Stevens and the guitarist Alun Davies had by this time established a deeply sympatico relationship, playing, in the words of one observer, “like one brain with four hands.” Samwell-Smith has also expressed amazement at Stevens’ ability to “double” a guitar part he just played, matching it perfectly.

“The Wind” begins the 10-song, 32-minute album, with the intimate, close-mic’d lead vocal sung live as Stevens and Davies play chimed acoustic guitars during an informal afternoon session at Morgan. Stevens’ voice is smoothly tender, and the words minimal, evocative and mysterious (“I listen to my words but they fall far below/I let my music take me where my heart wants to go/I swam upon the devil’s lake/But never, never, never, never/I’ll never make the same mistake”). Often played as a set-opener, Davies said, “It could calm an auditorium.”

The bouncy “Rubylove” was originally titled “Who’ll Be My Love?” before Davies’ four-year-old daughter renamed it. Two friends of Stevens’ Greek-Cypriot father play six-string bouzoukis, in an unusual dancing time signature, and Stevens even sings one verse in Greek. Larry Steele is on bass. The swooping background vocals are an inspired touch, with singer Linda Lewis blending in with Samwell-Smith, Davies and Stevens. “If I Laugh” features Stevens’ doubled acoustic (on the demo included with 2008’s deluxe CD reissue he plays 12-string) and lyrics which for the normally super-optimistic Stevens pass for melancholy: “If I laugh just a little bit/Maybe I can forget the chance/That I didn’t have to know you/And live in peace.”

“Changes IV” fades in on a quasi-flamenco rhythm, and Stevens sings much more aggressively than on most other cuts. The expert drummer is Gerry Conway (who’d played with Steeleye Span and Al Stewart and was a solid branch of the Fairport Convention family tree). He gets help from some percussion instruments rented for the session, including Alun Davies on claves; there’s also some nicely executed off-beat handclaps arranged by Stevens. The lyrics are once more optimistic and impressionistic, conjuring a time when “the beauty of all things is uncovered again.” Davies sings harmony, and there’s another effective overdubbed vocal chorus.

The slow and gentle love song “How Can I Tell You” ends the LP side. According to Samwell-Smith, Davies and guest guitarist Andy Roberts put down the acoustic guitars first, and Stevens overdubbed his vocal later. At the mid-point Roberts solos on a Kriwaczek String Organ, something like a pedal steel guitar, and Stevens adds very quiet harpsichord, fulfilling Samwell-Smith’s long-time wish to use the instrument as he did on the Yardbirds’ “For Your Love.” Linda Lewis does a little improvised flourish near the end.

The second side of the LP is where the set’s three biggest hits reside: “Morning Has Broken,” “Moonshadow” and “Peace Train” (all three were released in 45 rpm form). Eleanor Farjeon wrote the words to “Morning Has Broken” as a hymn in 1931, setting them to an old Gaelic tune. Stevens worked out the piano-led arrangement in the studio with Rick Wakeman, who by chance was working at another studio down the street and was invited spontaneously to join the session. Wakeman wasn’t credited on the album due to worries about “contractual issues,” which is unfortunate as his work on “Morning Has Broken” went on to become quite famous. Stevens’ vocal is a wonder, full of subtle changes in breath control and full of emotion. To add a “touch of unearthliness,” Samwell-Smith sped up the backing vocals for the last chorus.

Cat Stevens calls “Moonshadow” “the optimist’s anthem”: “If I ever lose my hands/Lose my plow, lose my land/If I ever lose my hands/I won’t have to work no more.” It’s a sweet song, with a melody inspired by a traditional Greek tune. It has a quite macabre edge, as matter-of-factly terrifying as an unexpurgated Grimm fairy tale. The instrumental arrangement is beautifully subtle; if you listen carefully you can hear the sound of coins held on fingertips clicking against each other as percussion. The track was engineered by Samwell-Smith when regular technicians Mike Bobak and Robin Black weren’t available for a hastily organized Sunday afternoon session.

Cat Stevens isn’t afraid to preach on the gospel-infused “Peace Train.” As he’s “thinking about the good things to come” he insists “everyone jump on the peace train/get your bags together/go bring your good friends too.” (Stevens later revealed he wrote the tune on a train, thinking about all the Hitchcock movies set on one, but there’s no lyrical tie-in.) Samwell-Smith pronounced the production “a bit of a mess,” but it’s hard to see what he’s driving at, except the technical challenge of finding enough room on the 16-track recording equipment for all the parts. There are dramatic builds, driven by drums, stabbing guitar parts, handclaps and a very good string section by veteran arranger Del Newman. “Peace Train” was Stevens’ first top 10 hit, reaching #7 in Billboard.

“Tuesday’s Dead,” which kicks off side two, was used as the B-side of “Peace Train” in America. It’s got a Caribbean lilt, with Conway drumming and Larry Steele playing congas as well as bass, plus singing the high harmony. Stevens plays two marimba solos, one rather buried in the mix and the other out front. “Bitterblue” has two double-tracked acoustic guitars, sleigh bells, vibraphone and organ, plus the ever-reliable Steele and Conway. Stevens also doubles his vocal this time, to somewhat harsh effect as he pushes and roughens his voice.

Teaser and the Firecat, with Stevens’ colorful and whimsical artwork on the cover, was released on Oct. 1, 1971, and eventually sold more than three million copies. His mid-’70s follow-up albums did nearly as well, with “Oh Very Young” and his version of Sam Cooke’s “Another Saturday Night” lighting up pop radio. For a while he was romantically linked to Carly Simon, and later he lived in Brazil for a spell. His career took a major turn in late 1977 when he converted to Islam, taking the name Yusuf Islam; he reduced his public appearances and musical output. Cat/Yusuf didn’t return to pop music until 2006 with his 12th studio album An Other Cup, releasing several new albums in the ensuing years, including an intriguing re-record of Tea For the Tillerman. In 2020 he oversaw excellent multi-disc CD/Blu-ray reissues of his first two Island LPs.

Related: Our 2016 live review of Stevens

Watch Cat Stevens perform live on the BBC in 1971

Related: Our review of the Teaser And the Firecat Super Deluxe Edition

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

3 Comments

For me, this is Cat Stevens best ever album. Sadly “How can i tell you” was never a hit (although in recent years, has been re discovered and “covered” by some important artists). Rick Wakeman s´piano on “Morning Has Broken” is a beauty, gentle and sublime. Alun Davies, by then, Cat Steven s´axeman did record one solo album that is really hard to find. Hope one day it is released.

great facts in there, don’t think you mentioned he was at the 9/11 memorial concert but wasn’t well-received due to some of his ‘pacifist’ comments 🙁

As great as Cat Stevens’ songs are, and as much unique and wonderful presence as his voice has, I’ve always felt like Paul Samwell-Smith really should get much more credit for making these recordings the sonically perfect things they are. There were so many singer/songwriters, who were folksinger type artists, that were becoming quite famous in those days, but none that I can think of had the AM radio perfection of Cat Stevens records. They didn’t sound like the recordings of just another folks singer, they were masterful recordings of great songs from a singer who sounded like no one else. But what they didn’t sound like were songs that were led by someone strumming an acoustic guitar. The percussive elements and choral background vocals in songs like “Peace Train” lift these recording high above most similar type artists of the day, and still sound amazing today.