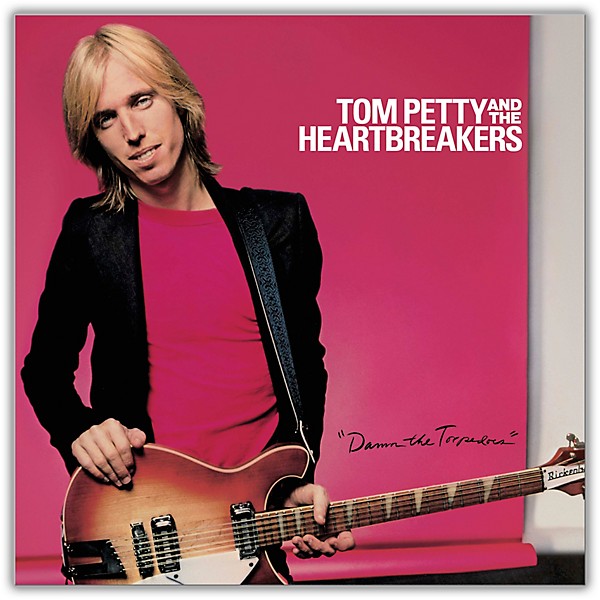

“Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.” That venerable slogan paraphrases the order Rear Admiral David Farragut gave to Union ships as they steamed through a minefield to challenge a Confederate fleet during the Battle of Mobile Bay, Alabama, in August 1864, risking disaster to seize victory. It’s a fitting title for Tom Petty’s third album with the Heartbreakers, recorded as he waged battle with a rapacious record company determined to hold the Florida rocker to a disastrous contract.

Originally signed to Shelter Records and its publishing arm, Skyhill Music, Petty had been persuaded to give away his song publishing in exchange for a small advance, recoupable against sales, and slim royalty rate. Two albums into their career, Petty and the Heartbreakers found themselves trapped in a virtual plantation system, still indebted to Shelter and its distributor, ABC Records, even as they began to carve out a fan base through radio play and live performance. When MCA Records acquired ABC and Shelter assets with it, Petty sought to void the original deal through an exit clause stipulating that right in the event of any change in ownership.

MCA’s refusal to surrender Petty’s contract triggered a lengthy legal battle as Petty took control of his career, financing the next album out of pocket. Jimmy Iovine, the ambitious New York engineer who had elevated Bruce Springsteen’s studio sound, was enlisted as co-producer, with the budget ultimately ballooning to over $500,000. Petty then held the album back, declaring bankruptcy and forcing MCA to void the earlier contract, renegotiate the overall deal and commit to major support as the first release on a new boutique subsidiary, Backstreet Records.

Petty’s confidence in holding his ground, as well as his audacity in underwriting a bank-breaking budget, was audibly vindicated seconds into Damn The Torpedoes’ defiant opening track, “Refugee,” a nominal love song laced with a sense of life as ongoing combat: “Somewhere, somehow, somebody must have kicked you around some,” he tells his lover before insisting “Everybody’s had to fight to be free.” His snarling vocal is framed by the taut interplay of the band, the arrangement pared to a coiled framework of Mike Campbell’s skeletal guitar riffs, Benmont Tench’s sweeping B-3 organ, and the locked-in rhythm section of bassist Ron Blair and drummer Stan Lynch.

Sonically, the band’s sound opens up to project both power and clarity, testifying to the band’s strength as a live unit: Petty would later tell journalist David Fricke that Iovine had driven them through over 100 takes to get a winning performance without resorting to overdubs or splicing multiple takes into a final mix.

“Refugee” would prove to be one of two top 20 singles, peaking at #15, while radio’s embrace of the album aligned with both critical and commercial acclaim and a broad consensus that Damn The Torpedoes was the band’s long-awaited breakthrough, the Heartbreakers now matching the caliber of their front man’s writing with their focused musicianship. The set’s first official single, “Don’t Do Me Like That,” was even more successful, reaching the top 10 on the singles chart.

The song was actually a holdover from Petty’s earlier band with Campbell and Tench, Mudcrutch. Written in 1974 while they were still based in Gainesville, “Don’t Do Me Like That” played to Petty’s strength in framing romantic conflict with hook-laden, upbeat elán, capped by an earworm-ready chorus that would have been a snug fit for the J. Geils Band, to whom Petty had originally considered giving the track. Peter Wolf’s loss was clearly Petty’s gain.

Petty’s sure instincts as a songwriter inform the structure of “Here Comes My Girl,” the third and final formal U.S. single release. A tough-minded valentine, the song’s verses set up their urgency through a measured ascent: Petty’s spoken delivery of the first four lines conveys a sense of defeat and hopelessness, then rises to an urgent melody as thoughts of his lover offer a renewed sense of purpose, followed by a joyful chorus in which he softens the rawness of his voice for a more lyrical attack. That three-step structure becomes a defining feature of the verses while also showcasing Petty’s dramatic range—his ease at being both street-wise and romantic, street-tough and idealistic.

The economy of Petty’s writing may have lulled some critics to underestimate his songcraft, but the level of quality on offer was measured by just how many of its nine tracks would see active rotation after its release, extended to evergreen status in the decades since. (That his songwriting peers knew better was evident early on: Having endured his own legal nightmare with prior contracts, Bruce Springsteen had counseled Petty to hang tough during the clash with MCA. Petty’s subsequent partners in the Traveling Wilburys signaled his stature as a peer.)

Thus, side one of the LP defied any impulse to lift the tonearm, following “Refugee” and “Here Comes My Girl” with “Even the Losers,” an outsider anthem every bit as powerful as the album’s singles (and released as one in Australia), followed by two full-throttle rockers, “Shadow of a Doubt (A Complex Kid)” and “Century City,” named for the westside L.A. urban cluster housing the law offices where Petty and MCA Records had dueled with opposing lawsuits.

Related: Our interview with the author of the book, Tom Petty and Los Angeles

Clocking in at a brisk 37 minutes, Damn The Torpedoes is a model of concision in both songwriting and arrangements, hewing mostly to brisker tempos that showcase the Heartbreakers’ surefooted attack and its underlying classicism. Petty and Campbell balance propulsive rhythm guitars and lead guitar filigree deftly, hewing one degree closer to Chuck Berry than, say, the Stones on vivid but brief solos, alternately cushioned and answered by Benmont Tench’s organ and piano. Their origins as a garage band schooled on the British Invasion, folk-rock and soul informed the playing, partially obscuring Southern roots otherwise explicit in Petty’s imagery and his proud drawl.

Those Southern accents emerge more prominently on the album’s majestic closer, “Louisiana Rain,” a wistful ballad that evokes Southern roots against a canopy of Tench’s organ, threaded with curving Campbell guitar lines that mimic pedal steel. The lyrics ponder the wages of experience as the singer concludes, “I may never be the same when I get to Baton Rouge.”

Released on October 19, 1979, Damn The Torpedoes brought Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers their first top 10 album, holding down the #2 rung on the Billboard album chart for seven weeks, blocked only by Pink Floyd’s epic The Wall. (The LP would finish 1980 as one of the year’s biggest sellers.) Triple platinum status would reinforce Petty’s willingness to joust with industry handlers as he would two years later over MCA’s attempt to increase album prices. On his final album for MCA, he would openly lampoon clueless record company execs on its title song, “Into the Great Wide Open,” with its rogue’s gallery of musicians and risk averse A&R men.

BONUS SONG: Damn The Torpedoes was intentionally streamlined from a larger pool of songs, including the atmospheric “Casa Dega.” Check it out here.

BONUS VIDEO: Watch Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers perform “Refugee” live at Farm Aid in 1985

Related: Tom Petty, a true rock ‘n’ roll star

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024

1 Comment

Sure miss the Gainesville Gator – Once in a generation lyricist, as well as musician, and entertainer.

Thanks for all the great songs that will live on forever.