In 1980, the celebrated music journalist Harvey Kubernik sat down for an interview with Tom Petty, whose career was still very much in its beginning stage but also in flux due to legal entanglements. That conversation was published in the now-defunct British music periodical Melody Maker, and is reprinted here for the first time.

In 1980, the celebrated music journalist Harvey Kubernik sat down for an interview with Tom Petty, whose career was still very much in its beginning stage but also in flux due to legal entanglements. That conversation was published in the now-defunct British music periodical Melody Maker, and is reprinted here for the first time.

Petty later penned the introduction to Kubernik’s 2014 book Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop, and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972, which is still available for purchase.

And they said it never rains in Southern California. Like hell, it doesn’t! Day after day after day of torrential rains nearly washed us into the briny depths. It was a nightmare. Woody Allen would argue it was a warning from the gods to amend our frivolous, hedonistic L.A. ways. It nothing else, it’s a reminder that there are larger forces at work than governments, oil companies and record labels. It’s a time, as Thomas Mann would say, to “take stock.”

Up on Sunset Boulevard, in the steel and glass that houses Lookout Management, Tom Petty sits high and dry. The rains have abated; as the city dries out and reflects, so does Petty. His career has weathered the storm and stress of musical indecision, legal snafus and the delirious ride to the top of the charts.

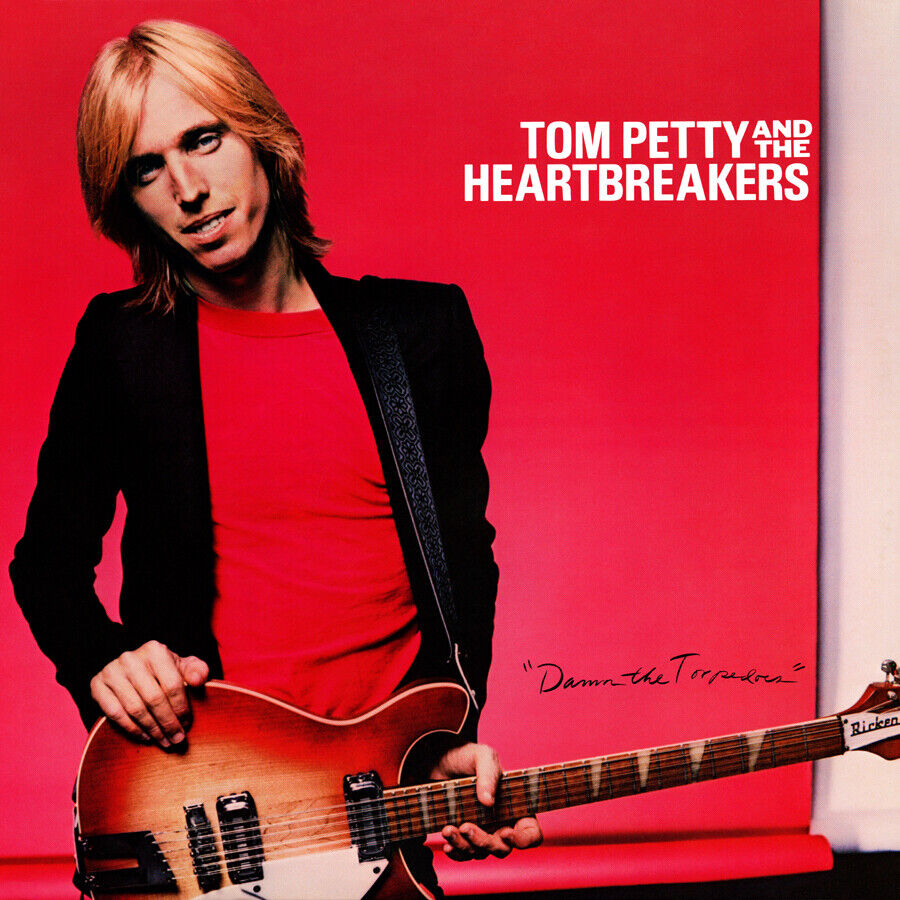

Since the release of his latest record, Damn the Torpedoes, Petty has tasted the glamour and gluttony of rock ’n’ roll superstardom. After existing for several years on the strength of a big cult following, Petty has broken through to platinum status, vindicating his unwavering commitment to authentic rock ’n’ roll values. “Somewhere, somehow, somebody must have kicked you around,” he sings on “Refugee,” his latest single. Beyond its assessment of alienation and love, it captures the true grit of rock’s primal scream. That’s the emotion that Petty taps in his music and in concert. Developing out of the “I’ll piss anywhere” school of rock ’n’ roll, first posited in American R&B music and later by the Rolling Stones, Petty and his cohorts the Heartbreakers are poised for the long haul, fully recovered from the ravages of the star-making chicanery.

Flaxen-haired, gaunt-faced, lithe, Florida-born, Angeleno by design, Petty is composed and uncommonly talkative during our conversation. And although the rock press has lavished voluminous praise upon his shoulders, he’s maintained a marked reticence in return. Now, though, fresh off a grueling tour of arenas and large halls in support of the new LP, Petty is primed for a bout of self-analysis.

“Playing large venues is both good and bad,” he says. “In one respect, it’s very flattering to the ego. The whole trick with the big rooms is to try and make them intimate. You get a whole new set of responsibilities. We did well at the Forum here in L.A. and we even managed to squeeze in a club date at the Whisky.

“My life has changed in the three years since we first played the Whisky, when we opened for Blondie. It seems like an eternity ago. I was watching the news recently and they were talking to these kids who waited hours to get in, and most of them said, ‘Wow, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers have got so big in such a short time.’ I guess to them it was a short time, but to me it’s been ages. The lawsuit alone seemed like ten years.”

He’s pleased that, wherever they go, they’re always introduced as Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. “I’ve always wanted it that way…so there was a band identity established, rather than me and whoever was in the studio at the time. Their identity is coming out more and more. It’s healthy.

Related: A live Petty box set is on the way

“Also, we’re not as uptight on stage as we used to be. On the You’re Gonna Get It tour [supporting their second LP], I noticed some things that weren’t happening. I saw a video of us on TV and it was so boring. We were all so stone-faced. Now we go out to have a good time and that shows up in every facet of the current live performance.

Listen to “I Need to Know” from You’re Gonna Get It

“Today, with the amount of money people spend going to a concert, they should get their money’s worth. You should be able to leave your conscious mind. I used to go listen at the black churches and it was amazing to watch the energy build until there was some kind of pop. From there it went upward, like a jet taking off.

“We need the feedback of the audience. I just spent a year not having contact with anyone. It was such a pleasure to come back and find that it was still there.”

The hiatus in Petty’s career occurred when his record label, Shelter/ABC, was bought by MCA Records. Petty contended that his contract entitled him to consult and cooperate in the process of selecting another record company to distribute his recordings, in the event that the pact between ABC and Shelter was ever terminated. Following the buyout, Petty believed himself to be a free agent, open to negotiate a new contract with whomever he wished, while MCA presumed him to be a new roster addition.

Push came to shove, and in a short time war was waged in the courtroom, prohibiting Petty from undertaking any musical activities. The legal entanglement was ultimately resolved by the intervention of MCA-Universal executive Danny Bramson.

Bramson, the 27-year-old booking agent for the Universal Amphitheatre and guiding force of Backstreet Records, an MCA subsidiary, proposed a compromise: Petty would sign to his label, keeping Tom under the MCA corporate umbrella while satisfying Petty’s demands for the attention and promotion he felt he’d earned. The deal was signed, vast sums of dollars changed hands, assuaging Petty’s enormous legal and personal debts, and all’s right in the world again.

Related: Our tribute to Petty, who died in 2017

“We did a small tour last summer in California, ‘The Lawsuit Tour,’ and it was great,” he continues. “I think the lawsuit tour ended the lawsuit. It contributed because it showed people that we could play in MCA’s own backyard and it could be pleasurable and in harmony. That’s when we started talking again.

“It was a bad experience being off the road, but it was good in one respect: if I’d been on the road, the record wouldn’t have sounded the same. Because all I did, to keep from going completely crazy, was write songs and get totally involved in the record. When we came back and played, I know it made us a lot closer. What the lawsuit did was bring us to a point of break-up, but we survived.”

The affair represented a crash-course in music-business ethics—“iIt was the first time I actually got to see how evil it could be, how rough they play.

“I’ve always said that there was a book in it [the lawsuit], but who’d want to read it? It’s such a miserable, ugly story that absolutely fascinated me by the sheer stupidity.

“They didn’t care if they destroyed my mentality, both emotionally and financially. I had to get mean and fight.”

Despite this, he maintains that the music business isn’t all bad. “I owe a lot to it,” he admits. “It’s fulfilled my lifelong dream. But on the other hand…musicians aren’t educated enough to deal with these people. The businessman knows how bad the kid wants the candy, but many times they don’t realize you have something equally valuable to offer them. Every kid in this town has had a dream and if it happens, where’s all the money gone? Everyone you supported has cars and a house in Switzerland, while you’re still living at the Tropicana Hotel [a sleazy hotel in West Hollywood].

“I’d like to think that our band helped pave the way for the things that are happening in town now. New bands don’t have to pay Top 40 music to get gigs. Kids will pay to see an unknown band do original material, and new attitudes will develop.”

Refreshed by that flight of candor, Petty pauses for a drink and resumes with a critique of his own music.

“In 1976 we were criticized for playing songs under three minutes. When we did our first album, we wanted a little garage sound, not a multi-track effort. Now everyone is into short songs and we’re back to stretching out.

“In 1976 we were criticized for playing songs under three minutes. When we did our first album, we wanted a little garage sound, not a multi-track effort. Now everyone is into short songs and we’re back to stretching out.

“We very rarely rehearse the tunes before recording them. ‘Shadow of a Doubt’ I wrote one night and recorded it the next morning. But now, when we play tunes on stage, we have a better understanding of what we want to do with them. We take our time and let them unfold naturally.”

Damn the Torpedoes represents a quantum leap in production values and thematic continuity for Petty. Enlisting the aid of New York fireball Jimmy Iovine to co-produce, Petty has crafted a convincing portfolio of the rigors of romantic alienation (“Refugee”), spiritual deprivation (“Century City”) and reaffirmation (“Even the Losers”).

The Heartbreakers—Mike Campbell (guitar), Benmont Tench (keyboards), Ron Blair (bass) and Stan Lynch (drums), all from Florida, as is Petty—ride roughshod over Petty’s structures, the sheer depth of their sound rivaled only by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. And Iovine, who engineered Springsteen’s last two albums, brings that same sense of immediacy and drama to T.P.’s recording.

This is a subject that Petty warms to without any probing: “I was looking for a new experience in the studio, a radical departure from the past. We did two albums in Hollywood in the same style, with Denny Cordell producing, and it was time for a change. Around the time we finished You’re Gonna Get It, Cordell played me Patti Smith’s ‘Because The Night’ and it completely blew my mind. I thought, ‘Incredible, who did it?’ Some kid named Jimmy Iovine.

“Anyway, time for the third record and I felt I needed a co-producer because I don’t feel I can keep a perspective on myself. I called Jimmy and asked him to come to L.A., and be obliged. I found out he worked on Walls and Bridges by John Lennon and, of course, [Springsteen’s] Born to Run, which are two favorite albums of mine.

“We met for the first time in the studio, and it was instant communication

“Jimmy and I agreed to have a more obvious bass sound on this album, because I missed it on the last two. I wanted to hear low end on the drums, and he knew how to get it. He taught the band a lot about rhythm; about relaxing and playing with swing. It’s one thing to play a pattern on the drums, it’s another thing to make it swing.

“The most radical change we undertook is that we moved into a large room to record. We used Sound City and Cherokee Studios rather than a small, tight one. He taught me that if you want to get that big airy type of sound you’ve got to be in a big room.”

Petty claims, too, that Iovine’s understanding of his legal predicament made the collaboration a lot easier. “Jimmy had been through the legal thing with Bruce, and he’d been through it with Lennon. Sometimes when we recorded, the legal hassles were going on in the studio. We’d have to drag out tapes and play all the things we’d recorded, and the court would log the proceedings: a vocal line here, a lead solo there. You wouldn’t believe what was going down.

“The scary thing was that I had to put all my money into that record to pay for it. I really had to over-extend myself. The lawyers would check out if we were cutting tracks and then demand we hand them over. ‘We heard you played a Chuck Berry tune, where is it?’ Then they’d take me into court and put me on the stand and really grill me for a good nine hours a day.”

Petty returned to England last week, to the scene of a triumphant tour that followed his debut LP. British bands now emulate his sound as Petty covers filter into the Isle.

Eager to return to the source of much of his musical inspiration, Petty recalls with mixed emotions his excursions to Britain: “England has always been a special place for us because they accepted us before anywhere else.

“You know, I remember when we were making this album, I kept thinking that this was an American album, the subject matter, the sound, the production. I used to read English reviews with things like, ‘He goes through women like Kleenex, a rock ’n’ roll gunslinger post!’ To me that’s a giggle. I’m not a poser. We’ve always been proud we were originally from the South before we landed in L.A. All the great rockers were from the South: Elvis, Jerry Lee, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins, Little Richard.

“Some of the English press have been trying to rub me out. Take the Knebworth gig last year. They gave us all kinds of shit…and I know the gig didn’t suck. I saw 100,000 people on their feet.

“We were at a disadvantage. The keyboard broke down on the first number, but we carried on. We played the festival because we didn’t have time for a tour, and that was the wrong thing to do.”

He enters the ’80s on a crest of critical and popular acclaim. In the few short years that constitute his recording career, Petty has experienced a roller coaster of highs and lows. Finally things have begun to stabilize, and he can settle down into the business of making music without the anxiety of being the businessmen’s next sacrifice.

“There was a sense of persecution throughout most of 1979,” he says. “I was being sued by so many people at once. Some were suing to protect themselves. I never gave in. It was so gruesome…I didn’t go over the edge with drugs. I did a little of that the year before, the ‘cocaine lifestyle,’ but I came to my senses. No drugs or drink were going to get me through the lawsuit.

“I’m finally feeling support from every level for the first time in my life. Management, record company, my family…it helps a lot. It’s bigger than I ever imagined it to be. But I want to keep a lid on it. I’m not interested in being a household word. I’m interested in making good records. I just really want to write good songs. Is that asking too much?”

Listen to Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers perform “Don’t Do Me Like That” in London in 1980

[easy_sign_up title=”Sign up for the Best Classic Bands Newsletter”]