Tom Waits had already traveled some miles off the beaten path when he released his first albums, 1973’s Closing Time and 1974’s The Heart of Saturday Night. Eschewing the melodic folk-rock styles of his Southern California musical contemporaries, he offered gruff vocals, bluesy, jazz-influenced music that evoked an after-hours session in a seedy bar, and lyrics that reflected the influence of beat writers and poets like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. By the time I interviewed him in early 1975, in fact, he was confessing that he was already “getting tired of hearing myself sing” and was experimenting with “talking bits” that he referred to as “metropolitan doubletalk.” Still, he wasn’t so far from the mainstream that one of his early songs—“Ol’ 55”—couldn’t be covered by the Eagles.

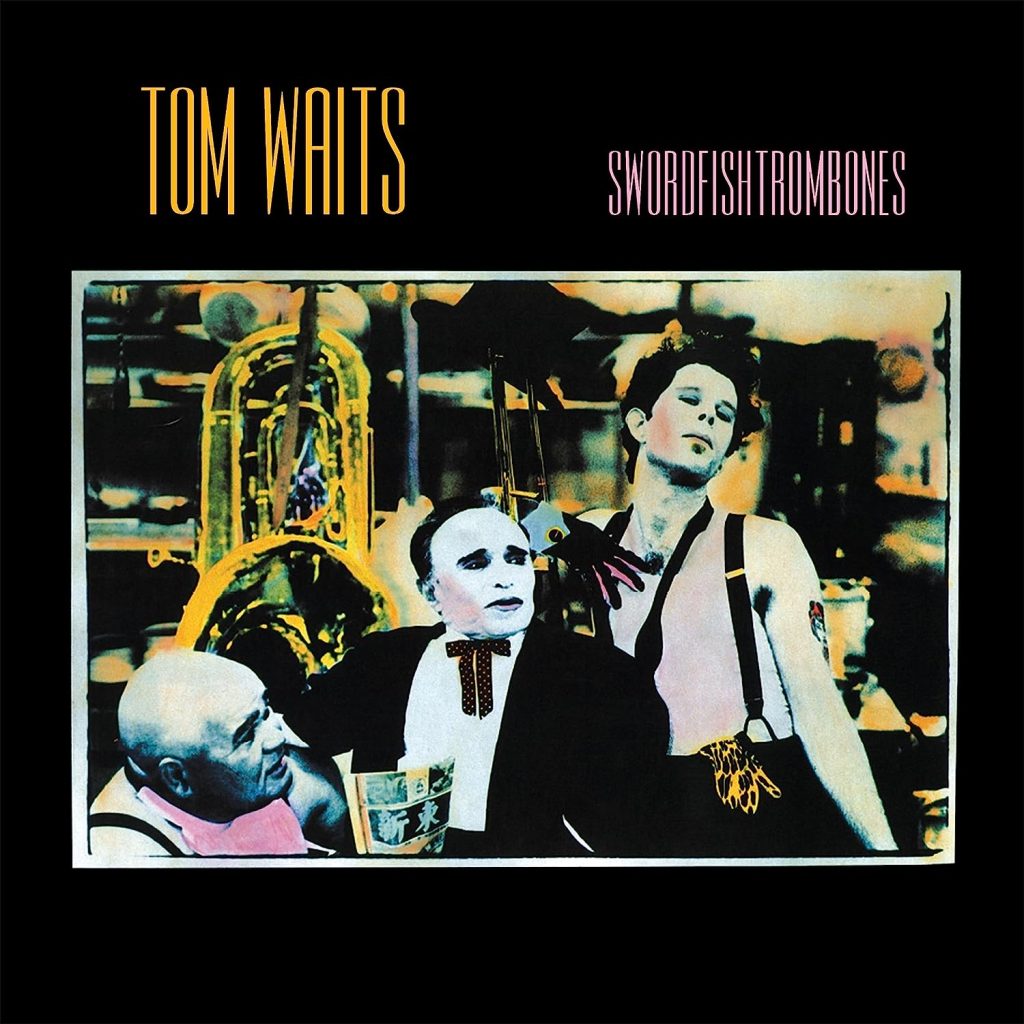

A turning point came with Swordfishtrombones. Waits’ label, Elektra/Asylum, reportedly rejected a version of the record, a decision that now seems as boneheaded as Columbia’s refusal to release in the U.S. Leonard Cohen’s Various Positions, the album with “Hallelujah.” Waits left Elektra/Asylum, signed with Island Records, stopped emphasizing piano and strings, and began producing his own LPs, starting with Swordfishtrombones.

A turning point came with Swordfishtrombones. Waits’ label, Elektra/Asylum, reportedly rejected a version of the record, a decision that now seems as boneheaded as Columbia’s refusal to release in the U.S. Leonard Cohen’s Various Positions, the album with “Hallelujah.” Waits left Elektra/Asylum, signed with Island Records, stopped emphasizing piano and strings, and began producing his own LPs, starting with Swordfishtrombones.

That album was “a line of demarcation for me,” Waits told writer Bret Kofford in 2000. “That’s right around the time I got married, and my wife [songwriter and musician Kathleen Brennan] worked on that record with me. She’s the one who said, ‘You can produce your own records. You don’t need to go in with a staff and people telling you what to do.’”

Swordfishtrombones, which came out in 1983, turned out to be part one of a loosely connected trilogy that also includes Franks Wild Years (1987) and Rain Dogs (1985). Remastered versions of all three of those LPs were reissued in September 2023, along with remasters of two subsequent albums, Bone Machine (1992) and The Black Rider (1993) in October. All five records offer evidence of Waits’ singular talent via soundscapes that draw on everything from blues, Kurt Weill and carnival music to Captain Beefheart, sea shanties and jazz.

Swordfishtrombones—which sold poorly but garnered rave reviews—is among the best of the bunch, with its novelistic tales and inventive use of instruments ranging from trombone, banjo and organ to bagpipes, marimba and African drum. One standout is “Frank’s Wild Years,” where a Hammond organ and acoustic bass provide backup while Waits speaks the story of a man who settled down with a wife and a little chihuahua in a two-bedroom house with a “thoroughly modern kitchen—self-cleaning oven, the whole bit.

“They were so happy,” Waits continues, but then: “One night, Frank was on his way home from work, stopped at the liquor store, picked up a couple Mickey’s Big Mouths, drank ’em in the car on his way to the Shell station. He got a gallon of gas in a can, drove home, doused everything in the house, torched it, parked across the street, laughing, watching it burn, all Halloween orange and chimney red. Then Frank put on a Top 40 station, got on the Hollywood freeway, headed north.” Concludes Waits: “Never could stand that dog.”

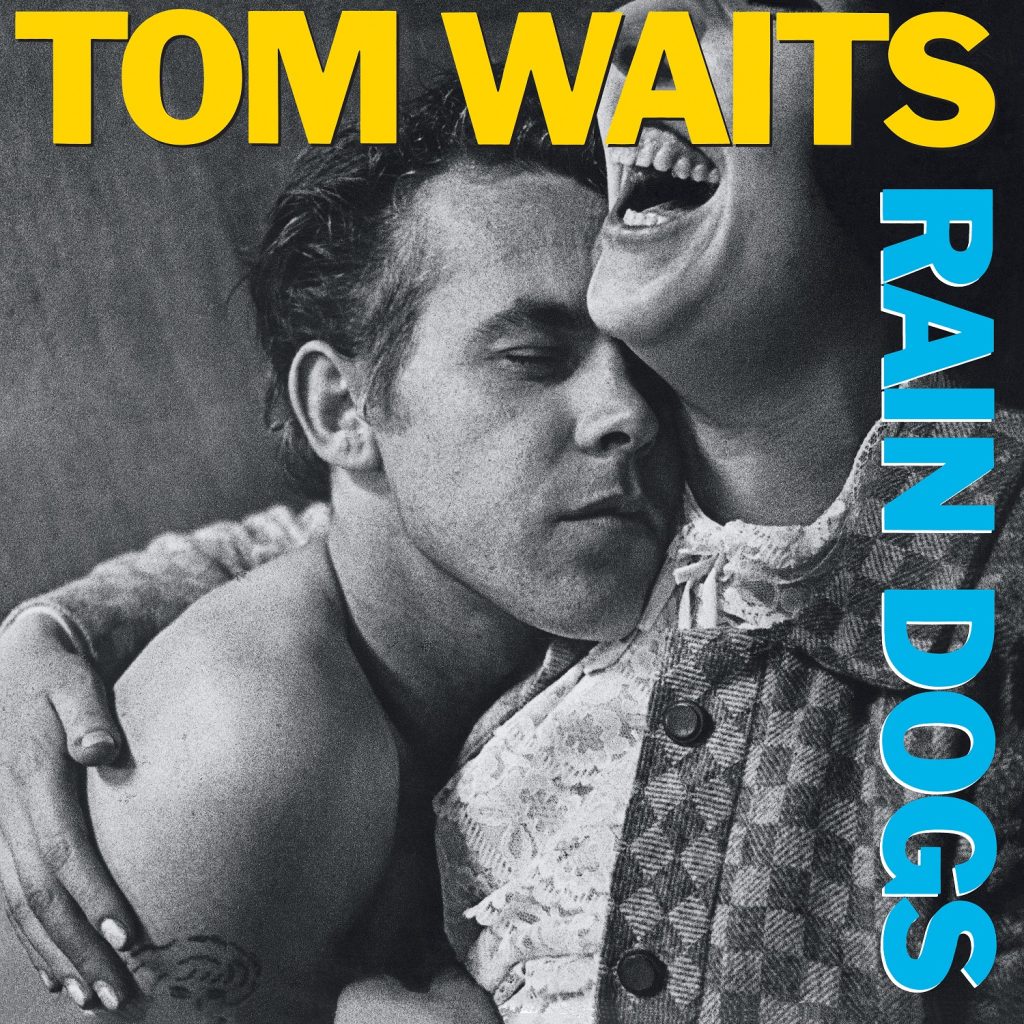

Speaking of canines, equally quirky stories imbue Rain Dogs, which is at least as good as its predecessor and employs a similarly surprising and eclectic mix of instruments. Some of the verse here is rather dense but it’s never less than colorful and the album includes at least one wonderful, accessible classic: “Downtown Train,” a number that Rod Stewart memorably rode up the charts five years later in a radically revamped version.

Speaking of canines, equally quirky stories imbue Rain Dogs, which is at least as good as its predecessor and employs a similarly surprising and eclectic mix of instruments. Some of the verse here is rather dense but it’s never less than colorful and the album includes at least one wonderful, accessible classic: “Downtown Train,” a number that Rod Stewart memorably rode up the charts five years later in a radically revamped version.

Arguably somewhat less successful but still ambitious, fascinating and occasionally brilliant are the last three albums in this reissue series: Franks Wild Years, a song cycle that evolved from a screenplay and borrows the title of the aforementioned Swordfishtrombones song (but drops its apostrophe for reasons unknown); Bone Machine, a Grammy-winning meditation on death and homicide; and The Black Rider, which features contributions from writer William Burroughs and stage director Robert Wilson.

Make no mistake: all five of these albums are challenging and not even close to anything you’d call radio-friendly (unless “radio” means freeform college stations). They’re not for everyone, but some listeners are bound to find Waits’ music rich and engrossing. Even those who are less enthralled will have to agree that it takes you to a place you can’t get to any other way.

Waits’ first seven albums were reissued in 2018.