Tom Waits middle-period albums–released on Island Records between 1983 and 1993—have been newly remastered from the original tapes and will be reissued on CD and 180g vinyl this fall via Island/UMe. The series kicked off on September 1, 2023, with Waits’ transformative creative breakthrough, Swordfishtrombones (1983), its sprawling sequel, Rain Dogs (1985), and the trilogy-completing, tragi-comic stage musical, Franks Wild Years (1987), 40 years to the day that Swordfishtrombones was released, ushering in a new and critically acclaimed musical era for Waits and his longtime songwriting and production partner, Kathleen Brennan. The epic song-cycle, Bone Machine (1992) and the under-appreciated Waits (with Robert Wilson and William S. Burroughs) musical fable, The Black Rider (1993), will follow Oct. 6.

The campaign has been personally overseen by Waits and Brennan. Ahead of their physical releases, all of the albums are available to stream now featuring the newly remastered audio. Stream the albums here.

All albums were mastered by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering under the guidance of Waits’ longtime audio engineer, Karl Derfler. The new vinyl editions will come with specially made labels featuring photos of Waits from each era in addition to artwork and packaging that has been painstakingly recreated to replicate the original LPs, which have been out of print since their initial release.

All albums were mastered by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering under the guidance of Waits’ longtime audio engineer, Karl Derfler. The new vinyl editions will come with specially made labels featuring photos of Waits from each era in addition to artwork and packaging that has been painstakingly recreated to replicate the original LPs, which have been out of print since their initial release.

More from the July 11 announcement: Waits went from ‘70’s-era “bluesy, boozy” wordsmith and melodist with seven albums behind him to sound sculptor, miner of the subconscious, abstract orchestrator, sonic cubist—while retaining his innate lyricism, melodic invention, humanity. A rough analogy: Picasso switching from exquisite literal depictions to pouring his brain and id out onto canvas. Waits was still painting, in other words, but the frames were made of blood and bone and feathers and old carburetors.

Working with experimental composer Francis Thumm, and taking inspiration from the music of found-object composer Harry Partch—plus Waits’ friend, Captain Beefheart—the renowned singer-songwriter reinvented his sound, album by album. As he put it in a 1983 interview: “I tried to listen to the noise in my head and invent some junkyard orchestral deviation—a mutant apparatus to drive this noise into a wreck collection.”

More details on each title appear below the Amazon links.

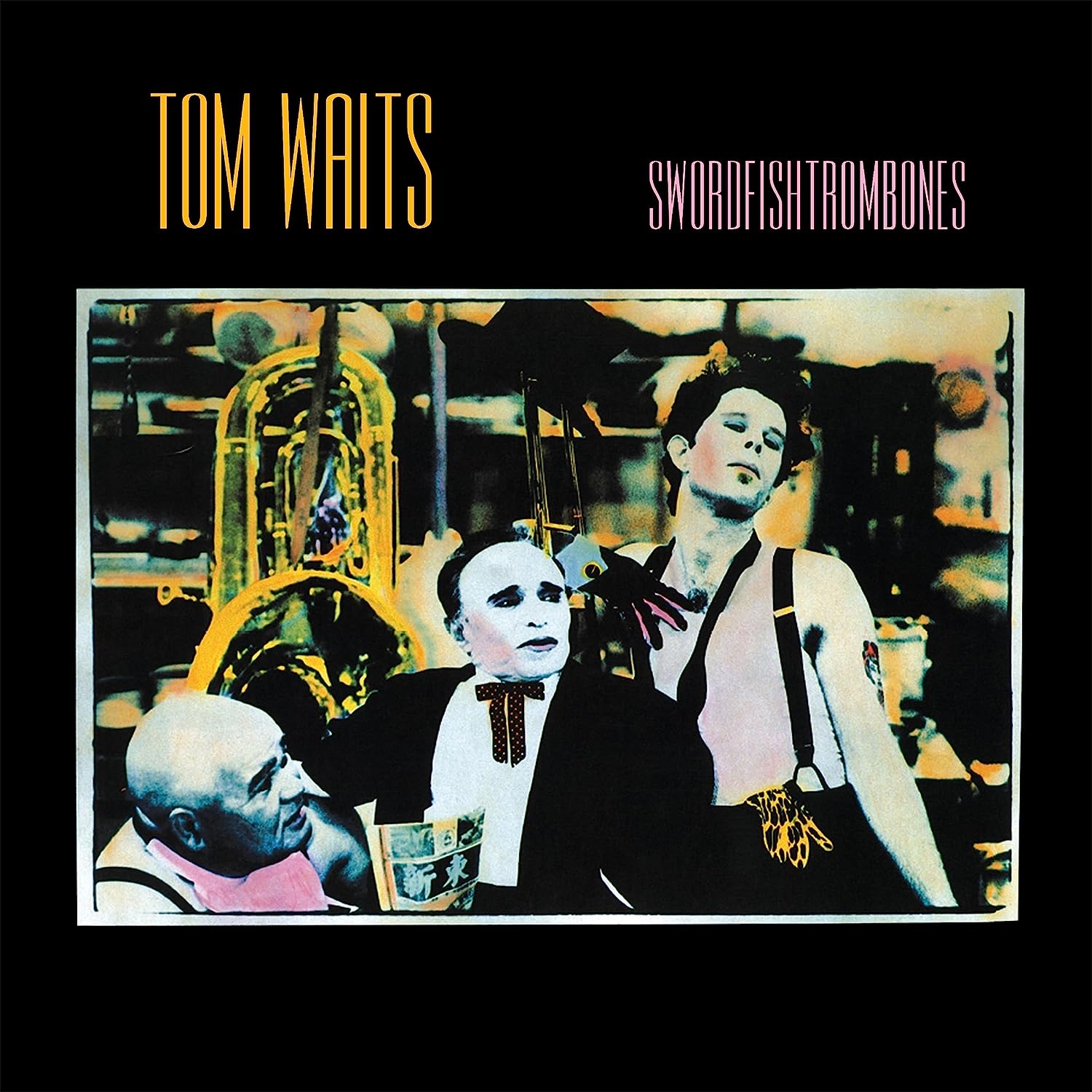

1983’s Swordfishtrombones (the title a winking tribute to Beefheart’s magnum opus, Trout Mask Replica) was a Waits-arranged pastiche, a variety of atmospheres from different sound planets. There is the warped, marching-army-ants music of “Underground,” an impressionist chant about people living below cities, but there was also the poignancy of the spare piano ballad, “Soldier’s Things,” the good bar yarn, “Frank’s Wild Years” (pre-figuring the musical of the same name), and the raggedy anthem to neighborhood chaos, “In the Neighborhood.” Yet the album was rejected by his long-standing record label, Asylum.

Waits was fresh off a 1982 Academy Award nomination for the “Tin Pan Alley”-style songs for Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart. Island Records founder Chris Blackwell promptly signed him and released the album, the first Waits produced. It earned rave reviews from Spin, Rolling Stone and the New York Times.

Rain Dogs came next—written in a Lower Manhattan basement and recorded in New York City. Waits and Brennan moved there in 1984, when Brennan suggested it might be good for creativity. She was right. The 53-minute, 19-track album was a kind of mutant, late 20th century musical “Canterbury Tales” with a shape-shifting band. There were banjos and marimbas and bowed saw and parade drum and howling horns (and Keith Richards and Marc Ribot) on this rollicking, rough-hewn opus—and Waits was using his voice in increasingly weird-and-wild ways. The songs were stories, sagas, laments, breakdowns, character studies, comedies, cabaret numbers, and the moving anthem, “Downtown Train,” which was later covered by Patty Smyth and Rod Stewart.

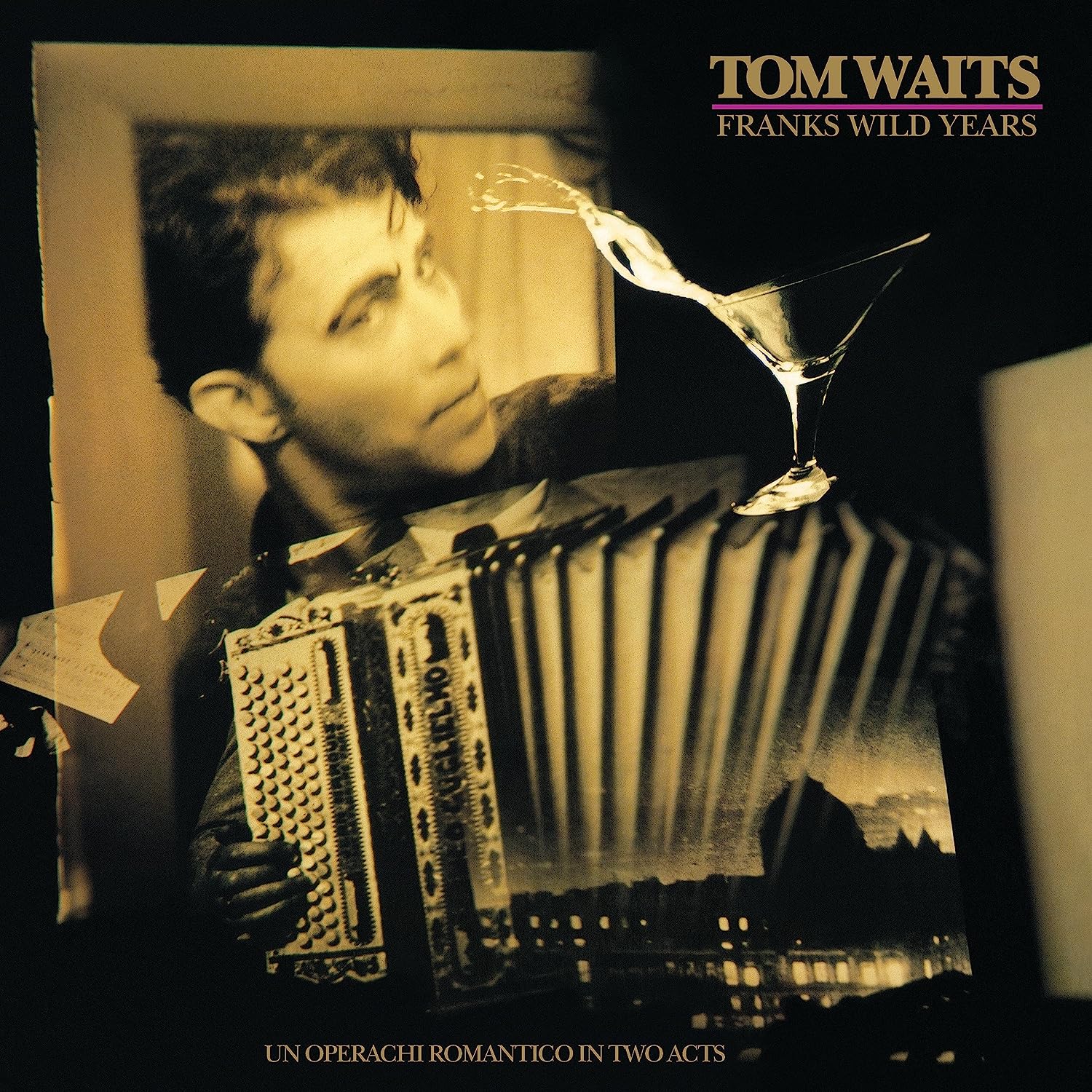

Franks Wild Years, the album, is based on the Waits musical of the same name, performed with Waits in the lead role by Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater (directed by Gary Sinise) during the summer of 1986. Recorded mostly in Hollywood, the idea for Franks came from the Swordfishtrombones spoken-word piece in which a used-furniture salesman (Frank), suffocating in middle-class existence with a “spent piece of used jet trash” wife and her blind Chihuahua, Carlos, burns down his house. With smoking rubble in his rear-view mirror, he hits the freeway with the parting quip, “Never could stand that dog.”

Franks Wild Years, the album, is based on the Waits musical of the same name, performed with Waits in the lead role by Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater (directed by Gary Sinise) during the summer of 1986. Recorded mostly in Hollywood, the idea for Franks came from the Swordfishtrombones spoken-word piece in which a used-furniture salesman (Frank), suffocating in middle-class existence with a “spent piece of used jet trash” wife and her blind Chihuahua, Carlos, burns down his house. With smoking rubble in his rear-view mirror, he hits the freeway with the parting quip, “Never could stand that dog.”

Waits and Brennan developed this into Frank as an accordion player escaping the mythical town of Rainville for a calamitous but noble journey to Las Vegas and New York, in search of stardom. In the end, broke and bewildered, Frank—“a guy who stepped in every bucket on the road,” as Waits put it—dreams his way back to Rainville, while freezing on a park bench in St. Louis. Until he suddenly wakes up and finds himself home in the saloon where it all started.

Waits’ vocal character varies wildly throughout the work’s 17 songs, and is no more impressive than when the gruff, growly singer turns to impeccable Sinatra-esque phrasing on the Vegas number, “Straight to the Top.”

“It closes a chapter, I guess,” Waits said when Franks was released. “Somehow the three albums seem to go together. Frank took off in Swordfishtrombones, had a good time in Rain Dogs and he’s all grown up in Franks Wild Years.”

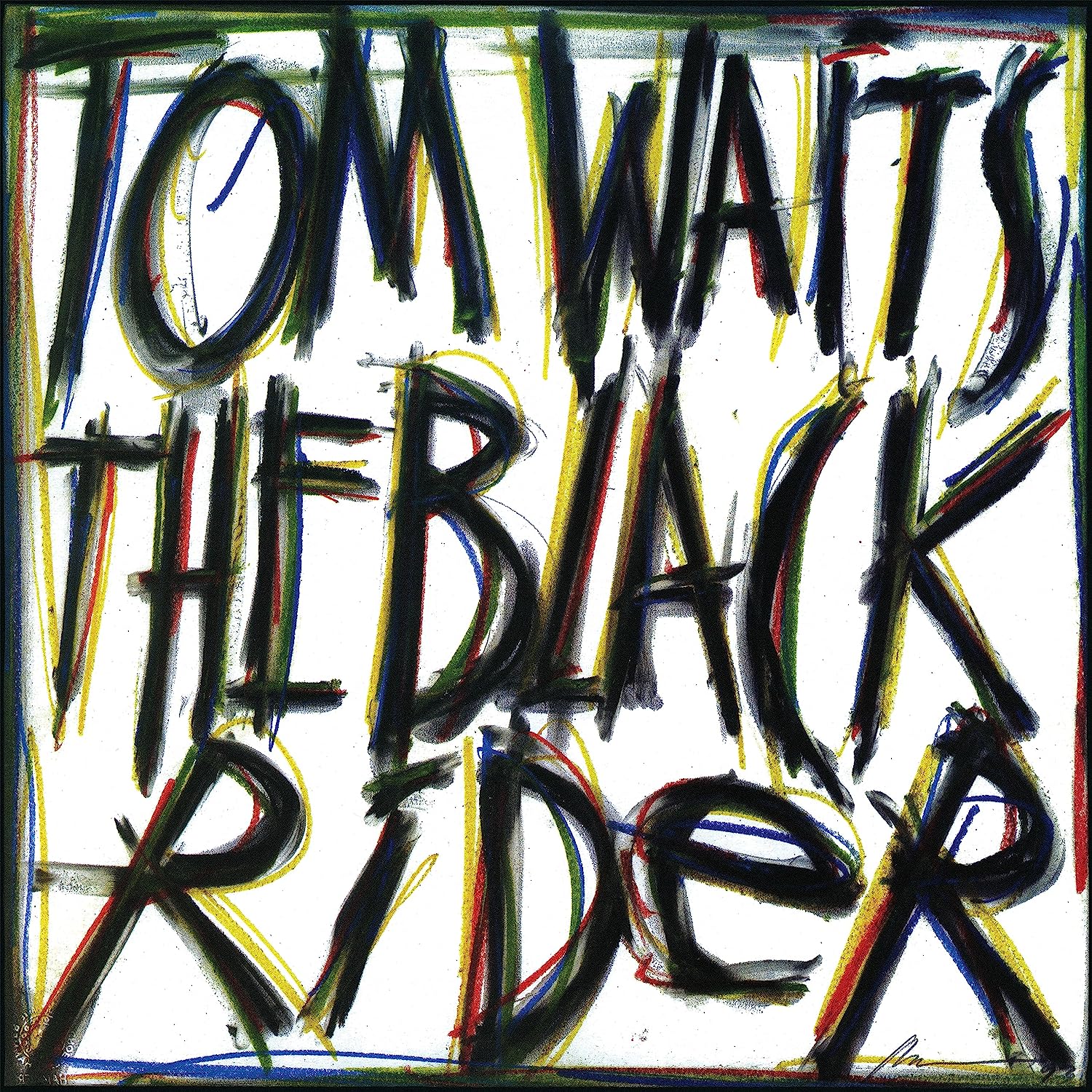

The Black Rider is an extraordinary melding of the art of three extraordinary persons: Waits, experimental director Robert Wilson, and the late legendary writer, William S. Burroughs.

The Black Rider is an extraordinary melding of the art of three extraordinary persons: Waits, experimental director Robert Wilson, and the late legendary writer, William S. Burroughs.

It’s is a nearly hour-long rabbit hole of grim narratives, hellacious carnival barking, fragile ballads, the eerie declamation of Burroughs poetry recited by both the author and Waits, and instrumentals. The “house band,” dubbed “The Devil’s Rhubato,” makes liberal use of horns, viola, cello, oddball keyboards, train whistle, contrabassoon, and sinister bass clarinet. The flavor of the music falls between the extremes of the poignant serenade, “The Briar and the Rose,” and Burroughs’ spooky “Tain’t No Sin,” which features a lyric that inspired Waits’ overall approach to the project:

“’Tain’t no sin to take off your skin / And dance around in your bones… ”

Bone Machine was a success—released in 1992 to universal critical acclaim, followed by a GRAMMY® for “Best Alternative Music Album.” Waits co-wrote half of the album’s sixteen works with Brennan, and special guests included David Hidalgo, Les Claypool (bass), and Keith Richards (who co-wrote “That Feel.”)

Recorded in Prairie Sun Studios in Cotati, Calif.—described by Waits as “just a cement floor and a hot water heater”—the album was a radical redesign of Waits’ soundscapes and writing technique. The songs weren’t composed—they sound more forged, hammered, chiseled, bent. Waits and Brennan seem to have conjured the record out of dirt, cracked pavement, broken tree branches, and bird song. Their move to a rural area of Northern California heavily influenced the ideas and music of the record.

Some of the press: Musician: “a raw-boned masterpiece.” New York Times: “Nothing short of breathtaking.” Chicago Tribune: “bursts with color and emotion.” Washington Post: “His finest album.” New Musical Express: “Scary, mournful, morbid and easily one of Tom’s best.”

Waits called the songs on Bone Machine “little movies for the ears.” He sometimes wrote them entirely from a percussion pattern, which he played on an array of largely homemade instruments.

Mortality is a recurrent theme, from “Dirt In the Ground” (“We’re all gonna be. . .”) to “All Stripped Down,” “The Ocean Doesn’t Want Me” (a tale of contemplated suicide), “Jesus Gonna Be Here,” the rambunctious paean to childhood, “I Don’t Wanna Grow Up,” and certainly the broken-hearted, confessional classic Waits ballad, “Whistle Down the Wind,” which was beautifully covered by Joan Baez. Waits explained at the time: “Yeah, ultimately, it will be a subject that you deal with. Some deal with it earlier than others, but it will be dealt with. Eventually we’ll all have to line up and kiss the devil’s arse.”

2 Comments

Just a correction: “Downtown Train” was covered by Patti Smyth (formerly of Scandal), NOT Patti Smith (the poet/rocker). Bob Seger also did it later on. .

Thanks for the catch, DGP. We copied-and-pasted that part of the announcement and should’ve caught that.