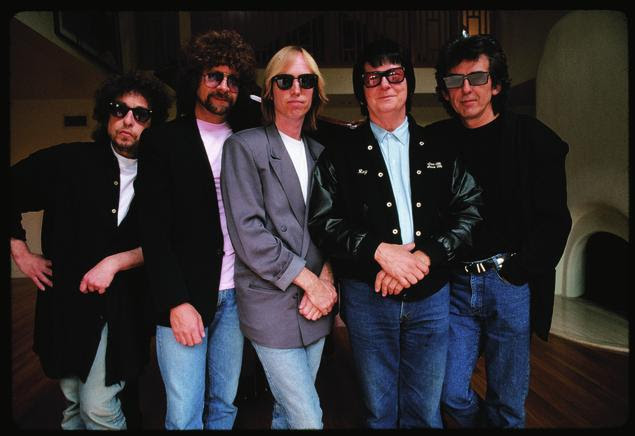

There’s no real definition of “supergroup,” but when the low man on your star-power totem pole is the bandleader of another enterprise that has sold 50 million records, it’s a safe bet you’re within its boundaries. And so it was with the Traveling Wilburys, the quintet of rock royalty whose debut, Volume 1, makes a strong case as the greatest collaborative effort ever delivered by an all-star team.

When 1988 rolled around, the five future Wilburys were all over the map professionally. Ex-Beatle George Harrison had just returned from a five-year album hiatus with the immensely successful Cloud Nine, co-produced (and given a sizable jolt of production personality) by ELO leader (and yes, future fifth-ranked Wilbury) Jeff Lynne. Legendary singer Roy Orbison was coming off a long fallow period that had run from the mid-1960s until the early ’80s, recently getting fresh notice with an album of re-recorded past hits. Tom Petty had reached a bit of a soft patch in his career, gaining little traction with his 1987 Heartbreakers set Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough). Bob Dylan was arguably at his illustrious career’s low point, coming off a string of unsuccessful records, most recent among them the light-selling and critically panned Down in the Groove.

The Wilburys’ record and band began the same way, with “Handle with Care.” In April 1988, Harrison, asked by Warner Bros. (home to his boutique Dark Horse label) for an extra track to fill out a European single release of “This is Love,” was at dinner in Los Angeles with Lynne and Orbison (who was working with Lynne on his then-forthcoming album Mystery Girl). Harrison and Lynne decided to record the track the next day, and Harrison invited Orbison to attend. By the next morning, Harrison was working up vocal parts to include Orbison in the session—waste not, want not to the nth degree.

Locating studio space proved difficult at short notice, so Harrison called on Bob Dylan to borrow his garage setup at Point Dume in Malibu. Harrison went to retrieve a guitar at Petty’s house, and asked Petty to tag along. They began collaborating soon after, with Dylan the last active participant when, if the story is to be believed, Harrison called him away from working the grill.

Although Harrison already had been mulling the idea of assembling such a band, the Wilburys felt like an organic enterprise, and its relaxed nature shows in the teamwork that resulted. The lone output of that first get-together, “Handle with Care” is an astonishing proof of concept, coalescing around the individual strengths of each band member. It’s like “We Are the World,” but with real collaboration.

Its opening is sonically in keeping with the production model of Harrison’s Cloud Nine, sporting a spacious, inviting pop/rock mesh pinned atop an inviting acoustic jangle. Harrison’s lead vocal gives way to Orbison’s plaintive touch and Dylan’s craggier presence in successive bridges before Harrison’s tangy lead takes the helm once more. It’s an array of wildly diverse voices plugged into a unified sonic vision that has room for all of them, combining to form a breezy, buoyant listen. Dylan’s harmonica floats in from the background, and by song’s end pairs with Harrison’s electric guitar in a sweet mixture. When Vol. 1 was released, “Handle With Care” was its first and most successful single, peaking at #45 on the Billboard singles chart, and reaching as high as #2 on the album rock tracks chart.

Before that could happen, the one-off needed to become a full-blown project, which developed quickly. Warner Bros. executives agreed “Handle With Care” represented too much opportunity to squander on a B-side, and with their blessing, Harrison and Lynne pitched Petty, Dylan and Orbison on uniting for a full record. The following month, they would reunite at the Los Angeles home of Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart—set up in a circle in his kitchen—where most of the recording for the album’s remainder would take place over 10 days.

The band’s second-oldest member behind Orbison, Dylan hadn’t been a surprise to listeners for a while at that point, which made the likes of “Dirty World” a revelation. Dylan leads the tune’s faux lasciviousness with uncommon playfulness, helped immensely by the other band members’ quirky, “He loves your…” responses and the throbbing structure of Lynne’s arrangement. Between honking horn accents and the cool choruses beneath Dylan’s barking, the song roams with cheerful abandon.

Lynne provides a rare vocal lead on “Rattled,” though Orbison’s enticing growls steal the show in a song whose beat is smacked out by Jim Keltner with split sticks on Stewart’s refrigerator. It fits the album’s anything-goes spirit, which also rears its head in “Last Night” as Petty leads a tune that overflows with texture from bass, drums and Jim Horn’s saxophone bounce. Along the way, Orbison’s bridges are lustrous and delightfully ominous, helping to create a song that’s as difficult to pin down as it is fun.

A descending synth pulse sets the tone for the futuristic throwback “Not Alone Any More,” with Orbison piloting it the rest of the way. His clean, singular voice matches an arrangement that’s all silk and polish until a curious drum cluster appears with 26 seconds remaining, as if throwing on the brakes for the song’s closing. Despite the rest of the group serving as an airy chorus, the slow-burn, Dylan-driven “Congratulations” is, memorable as it may be, the least collaborative-sounding song on the record, even accounting for Harrison’s lovely electric guitar decorations.

Dylan factors substantially into two other tunes, including a balancing act with Petty and Lynne in the breezy “Margarita.” An electronic pulse metamorphoses to propulsive acoustic guitars, and that wave breaks into a breezy chorus that dissects the title into individual syllables, with electric twang slathered atop it. It changes vocal gears into Dylan’s lead backed by a cooing chorus, and segues later to a comfortable Lynne interlude and Petty’s sly, “She wrote a long letter/on a short piece of paper,” using everyone differently along the way.

Dylan also propels “Tweeter and the Monkey Man,” a tale of the New Jersey badlands built solely to form a riotous parade of Bruce Springsteen clichés. Petty contributed to its writing, but Dylan sells its clever twist on Springsteen’s tropes with a smart, knowing reading full of amusing inflections. It’s the only track on the record on which Orbison doesn’t appear, but the rest of the group adds chorus punch, and the chunky arrangement benefits from Horn’s saxophone bleats and feathered keyboards that layer in spacey atmosphere.

Harrison’s leadership of the group feels more like camaraderie, even when he’s firmly in the spotlight with “Heading for the Light,” serving as a convincing steward of its uplifting message. Draped with springy guitars, big choral bridges and plentiful produced atmosphere, it’s also very much a Lynne song, sounding like a third-generation ELO track. Lynne’s signature production techniques are easy to underrate, but a listen to the unfinished outtakes “Maxine” and “Like a Ship” that appeared on the album’s 2007 CD reissue readily demonstrate how large a role his finishes played in giving the group a sonic identity.

Related: Watch Jeff Lynne sing “Handle With Care” with George’s son, Dhani Harrison

Harrison takes first watch on the set’s charming finale, “End of the Line,” propelling one last smartly designed trip around the band. Harrison and Lynne handle three chorus rounds each, Orbison takes one and Petty handles the verses in deliberate fashion, as each gives a sharp accounting of how to mold a lyric. Despite Dylan’s absence as a lead, it’s a sleek and easygoing conclusion to the set, and would serve as the album’s second single, reaching #63 on the singles chart and #2 among album rock tracks.

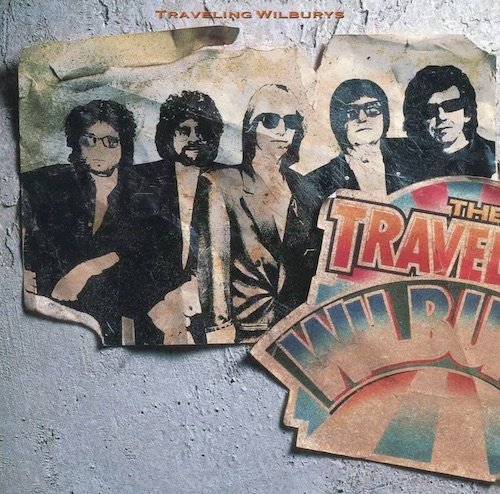

Released on October 17, 1988, Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 was an enormous worldwide success. It peaked at #3 on the Billboard album chart and was certified triple platinum. Its success would prove bittersweet when Orbison suffered a fatal heart attack December 6, just a month after completing Mystery Girl, which, when released posthumously the following January, was another big hit that climbed as high as #5 on the album chart. Three months later saw the release of Petty’s first solo album (with contributions from all fellow Wilburys except Dylan), the Lynne-produced Full Moon Fever, by far the biggest-selling non-hits record of his career. Dylan would put his solo work back on track with Oh Mercy that September, though his results would be hit-and-miss for years to come.

Harrison’s next project was a compilation of his most recent solo work to that point, and in conjunction with Lynne he set up a second Wilburys record, which the remaining four members would record in the spring of 1990. Traveling Wilburys Vol. 3 (the other members credit Harrison with the idea of skipping a number) would sell more than a million copies following its release in October of that year, and mark the end of the group’s output. Cohesive and enjoyable as the Wilburys project was, it’s a shame there wasn’t more of it, but both records—and the first one in particular—are landmarks of combining an array of distinctive voices into something no individual could create alone.

4 Comments

A few comments in this article about Jeff Lynne’s lack of starpower, yet also notes about how his input greatly affected the band’s sound.

Looks to me like a super talented guy that just avoided the spotlight.

One great computation of one of a kind artist. A must have in your library.

Dylan didn’t play harmonica on “Handle with Care.” That was Roy. My fun and fictional account of the recording of TW Vol. 1 is called Five Legends Five Guitars. Laced with facts like who played the harmonica derived from dozens of sources, five super-powered superstars write and record and album in only ten days. Google Pam Van Allen.

You omitted to mention the approach to Del Shannon.