After an eight-year odyssey of concept albums, bleeding-edge stage and movie projects, The Who confronted the prospect of their seventh album with a mixture of exhaustion and boredom. Returning to the studio after the innovative but chaotic Quadrophenia tour, the band entered the studio in April 1975 as Pete Townshend battled writer’s block, straining to write an album’s worth of new material.

After an eight-year odyssey of concept albums, bleeding-edge stage and movie projects, The Who confronted the prospect of their seventh album with a mixture of exhaustion and boredom. Returning to the studio after the innovative but chaotic Quadrophenia tour, the band entered the studio in April 1975 as Pete Townshend battled writer’s block, straining to write an album’s worth of new material.

Having mined generational identity as a core tenet for The Who’s music, Townshend was staring down his 30th birthday midway through recording and worrying whether the group’s relevance was waning. A decade after The Who’s salad days as Mod role models, the band’s songwriter, lead guitarist and chief creative officer was at a loss for grand themes, turning his attention inward instead.

That shift veered from the conceptual and narrative scale that had shaped Townshend’s music since 1966’s “A Quick One, While He’s Away,” written as a quick fix to a tactical challenge—the need to pad a sophomore album that was still nearly 10 minutes shy of target length. To bridge that gap, he assembled a six-part suite chronicling a lover’s infidelity dubbed as a “mini-opera” that would inspire him to push past stand-alone songs over the course of the band’s next four albums.

From the phantom radio broadcast of The Who Sell Out (1967) to the band’s definitive, pioneering rock operas Tommy (1969) and Quadrophenia (1973), Townshend’s songwriting was rooted in world-building. Even the concept-free Who’s Next (1971) extracted its evergreen hits and perennial deep cuts from the rubble of the doomed, Utopian multi-media blueprint for Lifehouse, which had collapsed under the conceptual weight of its screen, stage, record and interactive ambitions.

Four years later, Townshend began the new album with another relic exhumed from Lifehouse, “Slip Kid,” a cautionary rocker conceived as “a warning to young kids getting into music that would hurt them.” Blurring schoolroom and barracks, adolescence and combat, its lyrics depicted the plight of the title protagonist as “a soldier at 13…off to the civil war” that could work as parable for literal or figurative conflict. Forty years later, its allusions to fanaticism sound prescient in an era of fundamentalist terrorists abroad or homegrown white supremacists.

Watch the 2015 lineup of The Who perform “Slip Kid”

Musically, the track retreats from the orchestral scale of previous albums, building a lean arrangement from a syncopated drum beat and cowbell accents into a shuffle stalked by Townshend’s electric guitars and guest Nicky Hopkins’ bright piano flourishes. Roger Daltrey’s defiant vocal lines are answered by Townshend’s more vulnerable laments on the price of freedom.

Any expectation that the opener’s title character will serve as avatar for a unifying narrative is banished pointedly on the succeeding track, a starkly autobiographical high point for the album that harnesses its confessional pain to Townshend’s passionate lead vocal and an energetic performance by the band. Townshend’s withering self-assessment juggles disgust, despair and ultimately fear as he castigates himself as “a faker, a paper clown” who habitually lies, exaggerates his challenges and loses sleep as he agonizes over the source of his problems, “drench[ing] myself in brandy” in an unsuccessful attempt to quell his fears, nodding to demon alcohol in a real-life detail distinct from the fashionable psychedelia that had surfaced from “Magic Bus” and “I Can See For Miles” onward. A cycle of self-recrimination and defensive justification leads him to a harrowing verdict:

“I take no blame

I just can’t face my failure

I’m nothing but a well fucked sailor

You at home can easily decide what’s right

By glancing very briefly at the songs I write

But it don’t help me that you know

This ain’t no way out…

There ain’t no way out…”

The candor and ferocity of Townshend’s singing is reinforced by a kinetic arrangement powered by The Who’s thundering rhythm section, with Keith Moon’s exuberant fusillade braided by John Entwistle’s cascading bass figures beneath Townshend’s acoustic rhythm guitar and layered electric leads and fills, lucidly captured by veteran Who producer and engineer Glyn Johns.

To follow the exhilarating fireworks of “However Much I Booze,” the album seeks lighthearted relief in “Squeeze Box,” a loping celebration of sex that unspools as a nostalgic faux folk song that winks at a couple’s hearty carnal appetites. “Mama’s got a squeeze box she wears on her chest,” Daltrey observes, “and when daddy comes home, he never gets no rest, ’cause she’s playing all night…” The wordplay is anything but subtle as Townshend multitasks a lively “knees up” of accordion, banjo and guitar.

Eros invites a less genial, more sobering examination as Townshend reverts to his confessional mien on “Dreaming From the Waist,” replacing the optimism of the lusty elders of “Squeeze Box” with first-person anxiety over sexual self-control in the present and the specter of diminished potency that lies in his future. While Roger Daltrey resumes his post as lead singer, the lyrics’ anguish over the primal drive to “hump,” “jump,” “heat up” and “cool down” echoes the internal struggle of “However Much I Booze,” as do the instrumental fireworks set off by the band, with the rhythm section again explosive in its force.

On balance, it’s The Who’s focused ensemble attack that sustains interest for much of …By Numbers in the quartet’s agile power. As with Who’s Next, the project’s thematic modesty pushes the band toward its playing, even as Townshend’s autobiographical musings pull the lyrics inward and away from any grand design. That leaves welcome room for Entwistle to vent the band’s collective anomie and have some fun in the bargain with “Success Story,” an unfiltered snapshot of a rock band’s grinding path to glory.

The Who bassist may have ceded the band’s thematic preoccupations to Townshend’s dominant role in songwriting, but Entwistle’s original songs routinely flexed arch humor, here informing an anthem that valorizes then thumbs its nose at career milestones: “Back in the studio to make our latest number one, take two-hundred-and-seventy-six, you know this used to be fun,” sings a bored Daltrey in a lyric tipping Entwistle’s hand to the same torpor felt by Townshend and his other band mates.

For the balance of the album, the focus remains internal, musing over the authenticity of love (“They Are All In Love”), grumbling about false company (“How Many Friends”) and rambling through a loose catalog of quotidian pleasures in Townshend’s solo “Blue Red and Grey,” a ukulele reverie he would later claim to revile.

That sequence adds a melancholy reserve to much of the album’s second side that gives way to “In a Hand or a Face,” a concluding rocker that regains the band’s more exuberant energy.

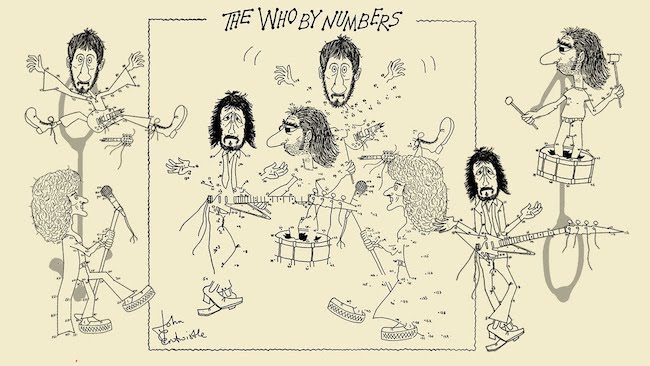

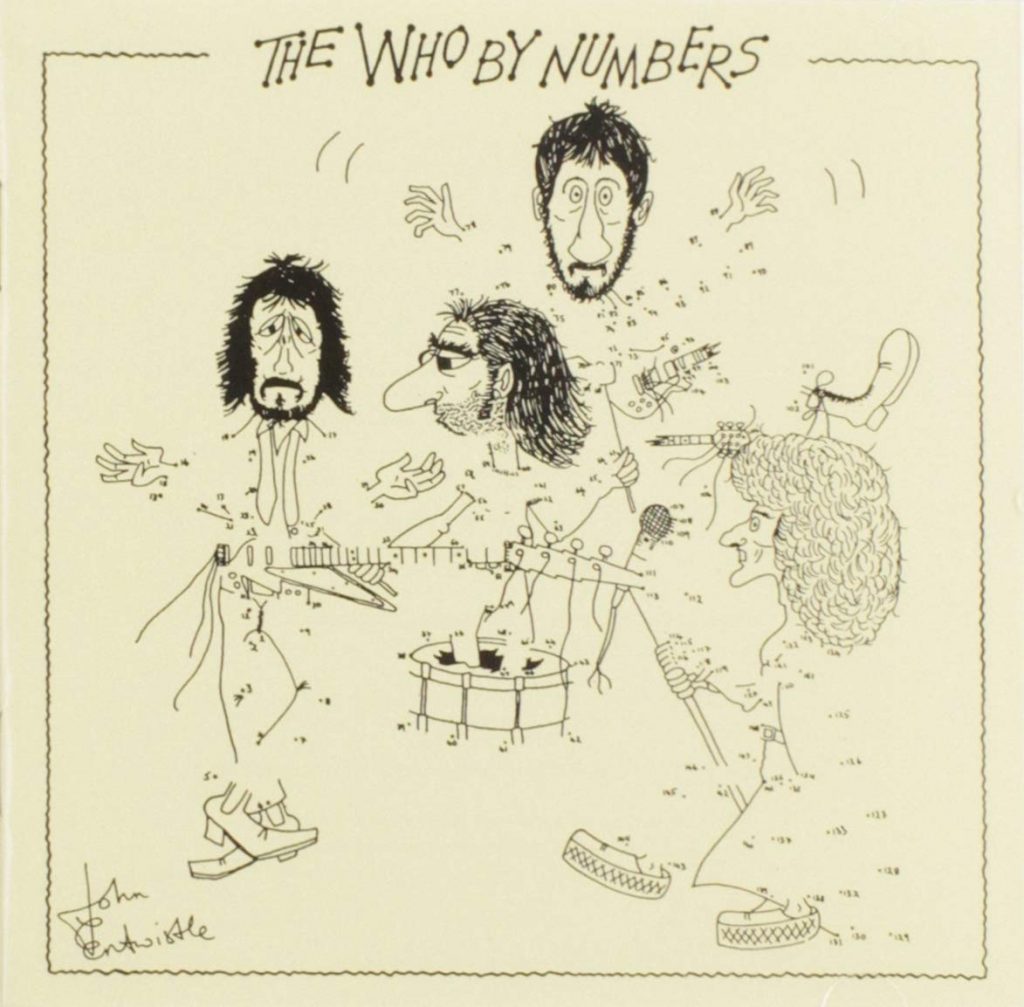

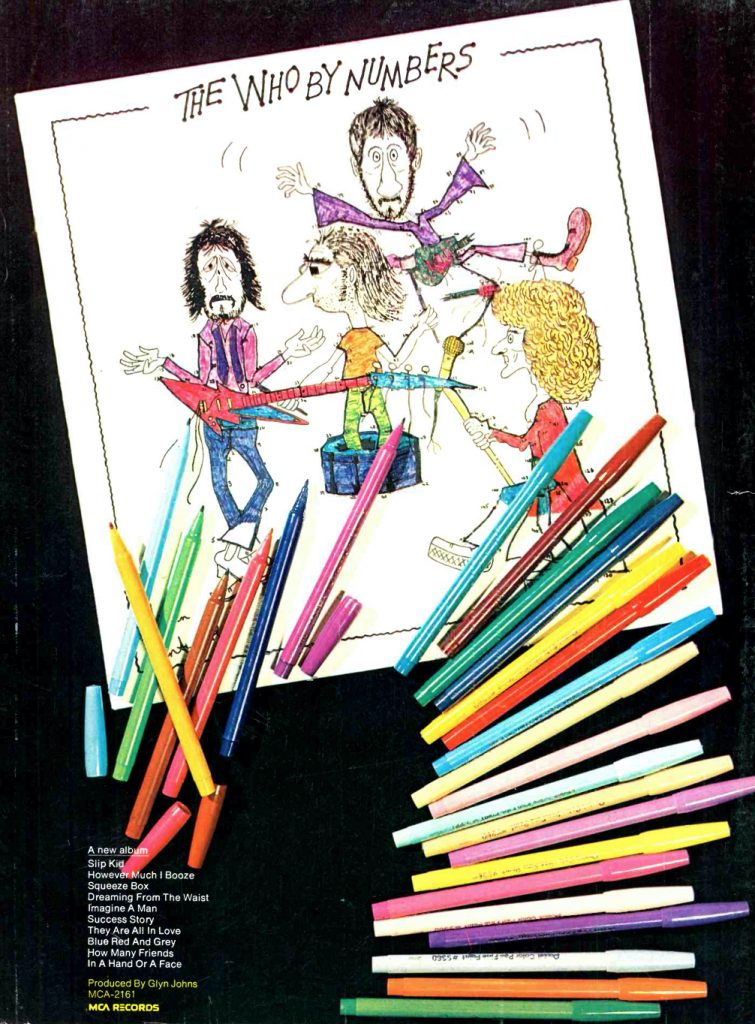

On his first solo album three years earlier, Townshend’s priorities were stipulated in the title, Who Came First. With his retreat from high concept on …By Numbers, his gravitation toward the personal would bubble up more frequently, both in subsequent Who albums and the parallel solo discography he would enrich in years ahead. The penultimate album for the original quartet, The Who By Numbers sustained the band’s reach into the top 10 on album charts upon its October 3, 1975 U.K. release (Oct. 25 in the U.S.), its modesty welcomed rather than critiqued by the rock press.

Watch The Who perform “Squeeze Box” live

Related: Our Album Rewind of The Who’s Face Dances

- Los Lobos’ ‘Kiko’: A Hallucinatory Masterpiece - 05/26/2024

- Neil Young & Crazy Horse’s Debut: Of Rivers and Cowgirls - 05/14/2024

- Steely Dan ‘The Royal Scam’: Rock on a Grand Scale - 05/10/2024