Musical revolutions typically are not long on subtlety. New directions are heralded by impactful moments, colorful gear shifts that reshape expectations with grandeur. Landmarks in every genre—rock to hip-hop to classical, Memphis to Liverpool to the Bronx to Vienna—reset standards with boldness and drama. True as that may be, every so often that pattern is upended by the rare sensation that demonstrates it is possible to be revolutionary by doing less, not least among them Willie Nelson and Red Headed Stranger.

Musical revolutions typically are not long on subtlety. New directions are heralded by impactful moments, colorful gear shifts that reshape expectations with grandeur. Landmarks in every genre—rock to hip-hop to classical, Memphis to Liverpool to the Bronx to Vienna—reset standards with boldness and drama. True as that may be, every so often that pattern is upended by the rare sensation that demonstrates it is possible to be revolutionary by doing less, not least among them Willie Nelson and Red Headed Stranger.

Watch a clip of Nelson singing a hits medley at the Grand Ole Opry in 1965

When the 1970s dawned, Nelson was a mid-tier country music performer who had transitioned to recording artist from Houston DJ with an all-world side hustle as a songwriter that yielded such standards as “Crazy” and “Funny How Time Slips Away.” His dissatisfaction with his recording path led him in 1972 to announce his retirement from making music, but it wouldn’t last—he soon negotiated an exit from his RCA deal to sign as the first country artist at Atlantic, which offered him the freedom to use his own band in recording rather than the session musicians RCA had mandated. He soon delivered 1973’s Shotgun Willie and the following year’s concept album Phases and Stages, each of which found Nelson stretching the boundaries of traditional country music with tastes of folk, jazz and blues. Sales were soft, but the records connected with younger listeners, and there clearly was something to what Nelson and like-minded artists, including Waylon Jennings, were doing.

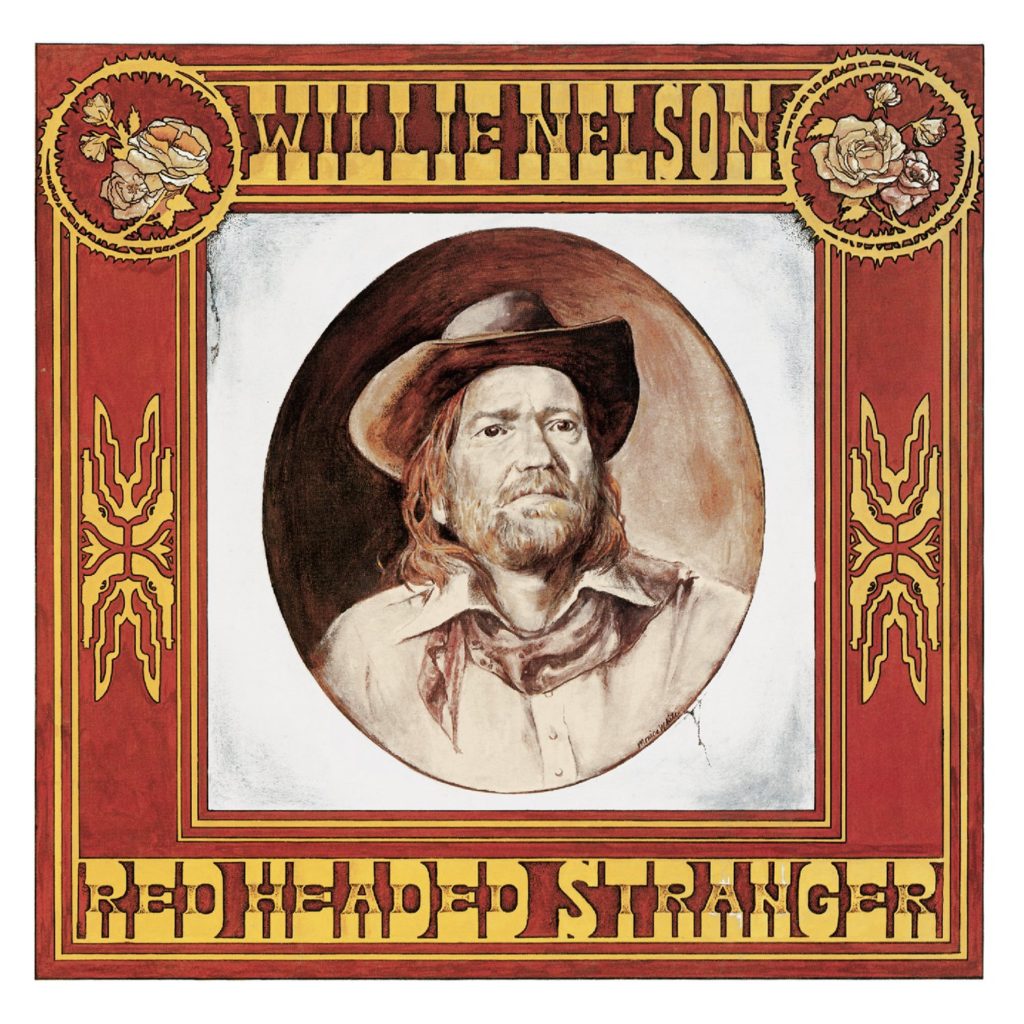

Nelson hopped labels again, to Columbia, which offered even greater latitude, guaranteeing Nelson full control over his album content. Emboldened by the opportunity, Nelson took advantage with a record that immediately put his new label’s commitment to the test: 1975’s Red Headed Stranger.

Music history is rife with success stories that begin with labels not knowing what to make of a visionary project, but in the case of Red Headed Stranger, Columbia executives were not so much puzzled as unimpressed. To their ears, it sounded like Nelson had turned in little more than a demo, a minimalistic cowboy concept record for which there was little market. They resisted when Nelson stood firm, and only after some cajoling on the part of Jennings did the label relent and agree to release it, which they did in May 1975.

There is always fun to be had in mocking hapless executives who couldn’t recognize greatness, but the fact is Columbia was right to wonder who was going to buy the record they received, for which there was no obvious audience. As it would turn out, Red Headed Stranger created its own market on its way to becoming a classic and helping fuel a wave of what would come to be termed outlaw country.

Red Headed Stranger ties together Nelson compositions with material from diverse sources to develop an overarching narrative; it is a concept album, but also a story cycle. The title character believes his woman to be unfaithful, tracks and then shoots her and the man she’s with, then moves on with his wife’s horse in tow, later shooting another woman who touches it—and that’s just on side one.

Shepherded by Nelson’s gentle quaver, the album’s stories are spun with a directness that evokes simplicity, yet sport an undeniable sophistication in their design. Album opener “Time of the Preacher” starts as a slow-walking cowboy tune but soon evolves, setting the stage when Nelson’s sister Bobbie floats lightly decorative piano alongside his acoustic playing, with dollops of Mickey Raphael’s soft harmonica checking in to evoke the sound of a panther in the night. Soon after his accompanists are established, Nelson heads off in a different direction with understated jazz inflections, subtly adding cool shading to its deliberate gait.

The set’s overarching thematic aims are bolstered by tracks called back along the way. “Time of the Preacher” shows up twice more, first as a minute-long contemplation and later in a 30-second interlude that by then is akin to a high-concept grace note as side one nears its conclusion. It’s similar to the way the title track rolls out, first entwined with the darkness and sorrow of “Blue Rock Montana,” and two tracks later in a fuller presentation of the song at which Nelson had previously hinted, a stout cowboy jazz. “Red Headed Stranger” is a killing song told in a cool tonal flow with thoughtful embellishments, ala Bobbie Nelson’s late-arriving piano trickle that subtly enlivens its gait before evaporating just as quickly for the final verse and chorus.

Nelson’s even-keeled delivery is the constant to combine material that doesn’t necessarily belong anywhere near together otherwise, forging common ground in the easygoing bounce of “I Couldn’t Believe It Was True” and a silky rendition of Fred Rose’s “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” The latter is a mesmerizing reverie arranged with a remarkably light touch, including a jazz-flecked guitar interlude that softly ornaments its middle portions, and a blink-and-you’ll-miss it snippet of choral backup on exactly one line—“We’ll stroll hand in hand again”—that quietly highlights how effectively sparse is the rest of the song’s vocal. It would become a hit that helped drive the record’s commercial success, topping the Billboard country singles chart and reaching as high as #21 on the all-comers Hot 100 in 1975.

An album long on subtleties is inevitably altered by modern playback. In its original conception, the 19th-century hymn “Just As I Am” finishes side one, an elegant, accordion-trimmed waltz to drop the curtain on the first act. On a continuous playlist, it serves as one of two instrumentals (the other being harmonica-and piano-dolloped Mexican classic “O’er the Waves”) between which the story vignette “Denver” is sandwiched. Beyond erasing the obvious breather that comes from having to physically flip vinyl, putting everything in sequence blurs the border to what is a very different second side.

Side two is less obviously of a piece than its obverse—Nelson’s mastery of understated emphasis intertwines everything, but gone are the repeating motifs and callbacks from the early going. It’s a distinction without a difference in terms of quality, as there is plentiful allure in the old-timey spring of “Down Yonder,” with Bobbie Nelson’s piano adding insistence to an airy concoction while Raphael’s harmonica buzzes around its edges.

Sparse, smartly targeted production enlivens a version of Hank Cochran’s “Can I Sleep in Your Arms,” which opens with a slender Bee Spears bass line behind Nelson’s wistful vocal before adding flowing acoustic guitar and piano a minute later. A chorus employed economically emphasizes rich individual moments rather than ongoing depth, part of a gentle journey that gives way to another breezy harmonica float to the finish. Similarly restrained is the design of “Hands on the Wheel,” where adornments serve as accents to a delicate alloy of Nelson and his jazz guitar that quietly lends the material power and poise.

Hardly overdone but certainly more full-bodied than most of the record is “Remember Me (When the Candle Lights are Gleaming),” a toe-tapper that swings atop Paul English’s drum rattle. Nelson’s vocal is nearly playful alongside its supple, piano-prodded bounce, tied to but never carried away by its energy. It was an obvious choice as a single, and proved to be a good one, reaching #2 on the country chart in 1976 and climbing as high as #67 on the Hot 100.

The record closes in self-assured refinement with “Bandera,” a lovely coalescing of keening harmonica, a deliberate bass underbelly and Nelson’s comfortable acoustic jazz alongside sister Bobbie’s decorative piano, helping the record’s cowboy story ride off into the sunset in a mellow finale. It’s a cap to a remarkable journey, one that listeners proved avidly interested in taking despite the label’s initial reservations.

Red Headed Stranger was an enormous success and a lasting one, topping Billboard’s country album chart and climbing as high as #28 on the all-genres chart, and proving an evergreen success that would achieve sales of more than two million by 1986. It also helped define Nelson as an iconoclast comfortable on his own path, which he would follow in singular fashion for decades to come.

Related: What were the other great albums of 1975?

Watch Willie and Shania Twain duet on “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”

Nelson has a typically busy concert schedule planned for 2024. Tickets are available here and here. His vast catalog is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

Related: Our Album Rewind of 1978’s Waylon & Willie

2 Comments

Great review. I can’t remember exactly when I picked up this album, but I played it incessantly for years and never tired of it. Willies unique voice coupled with the remarkable tone of Trigger are a national treasure. Another great concept album that never got the recognition it deserved was Domino Joe by a Tucson group called the Dusty Chaps. A bit more honky tonk but cowboy poetry none the less.

Willie is Willie! There will never be another.

I have worn out many needles listening to Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. (You youngsters probably don’t know what a needle is). Willie Nelson has done more to promote country music than anyone . Either you like him or you don’t. If you don’t, well we Texans say don’t let the door hit you in the butt on the way out! Willie is a national treasure.