The summer after my final year of junior high, I became a full-fledged British Invasion addict… some two decades after it all actually happened. I wore out a number of Beatles tapes that summer while on vacation. I’d read about them too, and when you read enough about one band, you start to see references to a horde of others. Bands that your favorite band were influenced by, had an influence on, competed against, despised, what have you.

So it wasn’t long before I was awash in British Invasion bands: the Stones, Gerry and the Pacemakers, the Hollies. I liked The Animals better than anyone but The Beatles, because their sound was tough, even tougher than the Stones.

The Animals had finesse too, like the Beatles, though not nearly as much range. The Beatles would come at you from a number of directions; you never knew how they’d build up their sound. Sometimes, a track hung everything on the drums: the riff, the melody, the vocals. Other times, a song was all voices, one harmony leading into another. They’d serve up plenty of guitar cuts too, with cheeky licks, and avant-garde flourishes – feedback, backwards solos, guitar parts filtered through Leslie organ speakers.

The Animals built everything up from the organ and Eric Burdon’s voice. They were so good that you could listen to them again and again and not get bored, but they also felt primitive to me. Or industrial, maybe, like The Animals – who hailed from the far northern English industrial and mining city of Newcastle – were the rock ‘n’ roll equivalent of a 19th century factory novel, jammed with hulking edifices, chary smoke on the horizon, grubby fingers and row houses.

All of those bands played electric music, of course, but I wanted something more electrical still, like it was made out of dancing lighting, all bendy and flashy and protean. Something that could practically make you hear the protons and neutrons bouncing off each other.

I remember reading one quote in some music book I’ve never been able to find again that said – and I think this might be exact – “There are exactly four rock bands that matter, and The Yardbirds are one of them.” Hmmm. The Beatles and the Stones must have been two of them; I didn’t know who the third was – Kinks? Beach Boys? The Who? – but The Yardbirds, eh?

If you’re a new Best Classic Bands reader, we’d be grateful if you would Like our Facebook page and/or bookmark our Home page.

A Different Breed of British Band

They were another British band, but not really a British Invasion one. As far as I could gather, they were too out there for that. Not sufficiently poppy. The Stones weren’t all that poppy, but they made for a good contrast with the Beatles, and everyone could say the Beatles are angelic and kind while the Stones were salacious and filthy. Total hogwash on both sides of that ledger, but there was a very workable schism there for journalists who probably didn’t care for either group.

What you mostly read about the Yardbirds was this blather about how they served as a preparatory school, of sorts, for three guitar gods: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. The prep school angle suggested, of course, that the Yardbirds weren’t the end-all-be-all, but rather something skilled players passed through, on their way to that eventual end-all-be-all. As misleading as it gets.

The rest of the band could bring it, too: Jim McCarty was a fine blues-rock drummer, Paul Samwell-Smith had a melodic touch on the bass, and rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja freed-up space for the band’s various guitar titans to do what they did.

But classic rock fans who are into Clapton tend to gravitate to Cream or his solo work. Page admirers nearly all fall in with the hordes who worship Led Zeppelin. Beck followers tend to be more open to variations from following his wide-ranging musical path through a host of stylistic realm. But it seems most people treasure what all three did after The Yardbirds. Yet The Yardbirds are what captivated me, and where the three esteemed English rock guitar heroes did much of their most exciting and innovative work.

Clapton, whose Yardbirds tenure went from 1963 into the early spring of 1965, would go on to blues purism with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and then form Cream with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker – a juggernaut of a supergroup if there ever was one (and a band, ironically, that fostered the same kind of longterm fan base as the Yardbirds; i.e., a legion made up of loads of musicians), and then eventually toss off lots of solo career twaddle that pleased plenty of housewives and Foreigner fans.

Enter Jeff Beck, who was more of a renegade, a drifter, a hired gun who frequently was not for sale, save when he wanted to follow his own idiosyncratic career path. Page, who came on board and played bass for a while with Beck in the band, would of course later launch Led Zeppelin, and there was even a brief period where Beck and Page co-teamed on lead guitar for the Yardbirds until Beck dropped out in 1966 and Page saw the band through to their end in 1968.

Related: Our Album Rewind of Jeff Beck’s 1968 solo debut, Truth

Untangling The Yardbirds Legacy

Even as a teenager who was new to all of it, I could tell how messed up their discography was. It was like no one in the band or managing them had ever thought to record proper albums, like everyone else was doing by then, or put the Yardbirds in a studio that was up to snuff in terms of helping them get their sound down on tape. So there were a lot of gappy greatest hits tapes.

You’ve probably heard a song like “For Your Love” on the radio. Oldies stations love it. Clapton, though, hated it, and absconded, slagging the band off as a bunch of pop merchants who didn’t want to make blues music so much as climb the charts and cause some teenyboppers to scream and wet themselves in the process.

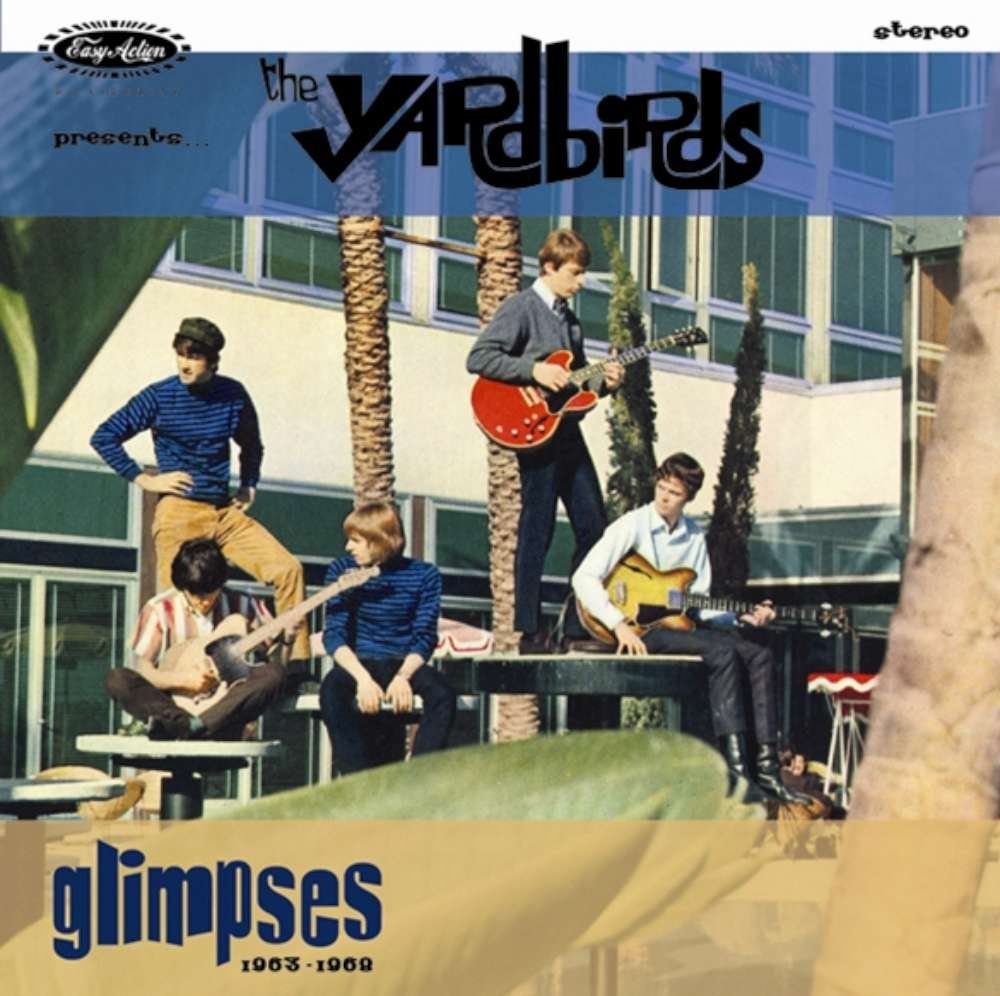

The band then asked Jimmy Page to join. He turned them down, given how much success he was having as a session guitar player. But he was kind enough to recommend his buddy, Jeff Beck, and it is the Jeff Beck incarnation of the Yardbirds that we can hear as we’ve never heard it before on a 2011 boxed set called Glimpses: 1963-1968.

The band then asked Jimmy Page to join. He turned them down, given how much success he was having as a session guitar player. But he was kind enough to recommend his buddy, Jeff Beck, and it is the Jeff Beck incarnation of the Yardbirds that we can hear as we’ve never heard it before on a 2011 boxed set called Glimpses: 1963-1968.

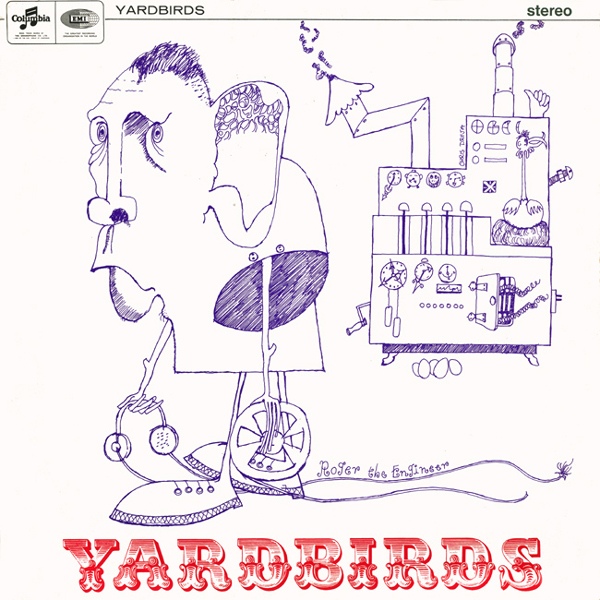

Basically, here’s what we had, pre-Glimpses: a live set recorded at London’s Marquee Club in 1964, additional live cuts from ’63 (all with Clapton); a number of studio tracks from ’64 and ’65 (the latter featuring Beck) that were shoe-horned into a couple of spotty albums with the earlier live material thrown in; some vanguard singles from ’66 that would have blown someone like John Coltrane’s mind, plus the band’s one proper studio album with Beck, Roger The Engineer, from the same year. A second studio album, Little Games, with Page, from ’67, plus some more live material as the band became more and more Zeppelin-like, culminating Live Yardbirds Featuring Jimmy Page, one of the rarest LPs of the 1960s – because Page had it suppressed, basically – waxed at NYC’s Anderson Theatre, with canned applause.

There were also a number of cuts recorded live on BBC radio. Most of these feature Beck, and, as they are live recordings, after a fashion, Yardbirds zealots have regarded them as manna over the years. You ain’t a Yardbirds buff unless you delight in the BBC material. It’s the big boy stuff.

In recent years, the discovery of another ‘64 live tape from the Marquee (which is included on the Glimpses box) has bolstered the discography, but back when I got into the Yardbirds, it was pretty easy to be confused as to what all the fuss was about.

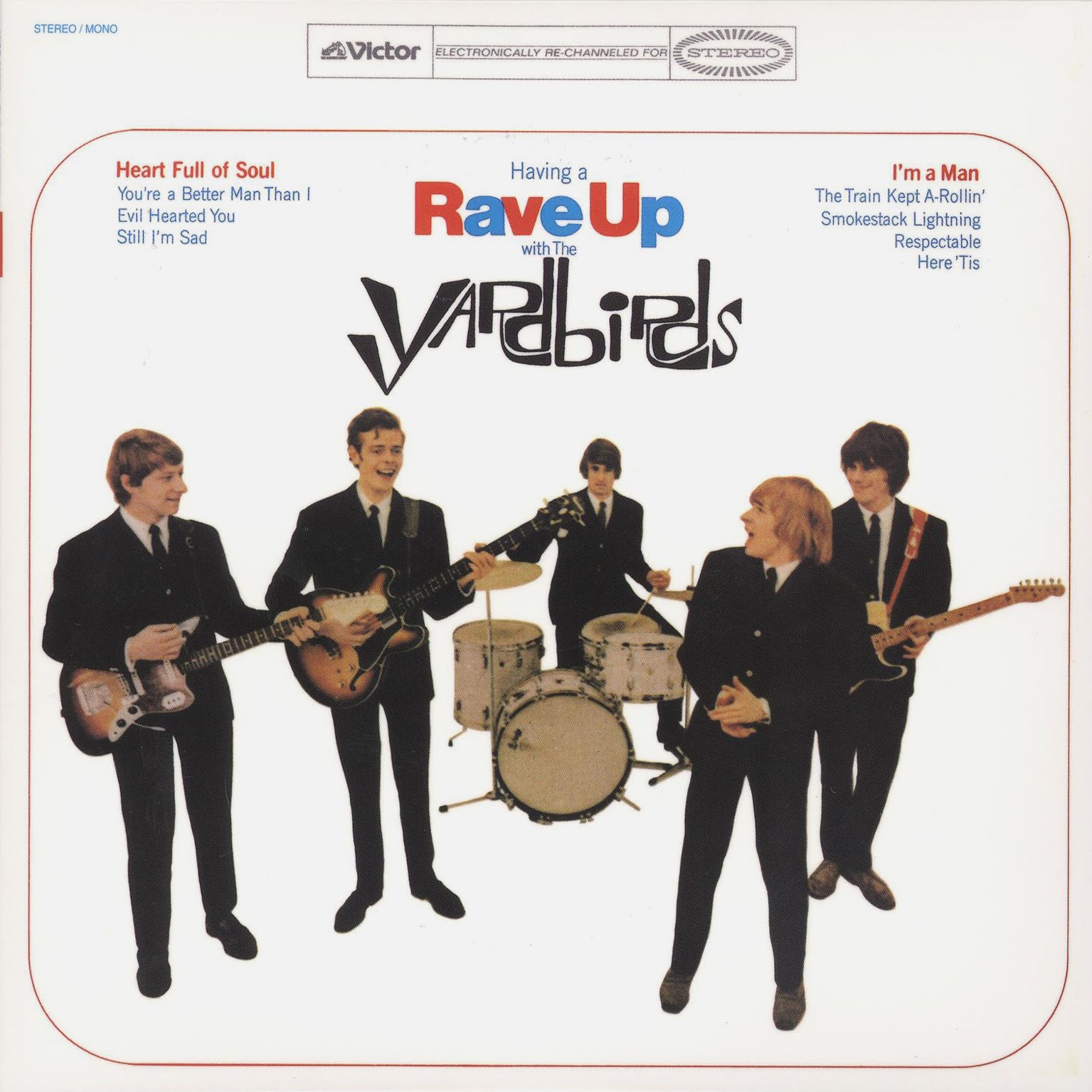

Not that they couldn’t bring it. Only the Beatles – and we’re talking vanguard Revolver/Sgt. Pepper’s era Beatles – to my ears, brought it like the Yardbirds brought it on the singles that Beck lashed along. Tracks like “Heart Full of Soul,” with its riff that sounded like someone had plugged in a sitar and uncorked the most serpentine ostinato figure that anyone had ever heard. “Shapes of Things” and “I’m a Man” were so out there as to be off the musical grid.

“Shapes of Things” had a solo that defied you to identify how anyone could even play it, let alone play it yourself. Singer Keith Relf might as well have been some Yeatsian sage, the herald of the future of sound itself, or maybe some prophet who’d lately been hanging out in the Book of Revelation. There was prescience in his voice, something supernal.

“Shapes of Things” had a solo that defied you to identify how anyone could even play it, let alone play it yourself. Singer Keith Relf might as well have been some Yeatsian sage, the herald of the future of sound itself, or maybe some prophet who’d lately been hanging out in the Book of Revelation. There was prescience in his voice, something supernal.

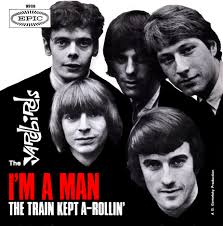

“I’m a Man” was the old Bo Diddley number, but the latter’s machismo had been replaced by what you might think of as something out of H.G. Wells, a kind of rock ‘n’ roll sci-fi. We get to the end of the song, and then it’s s rave-up time, a Yardbirds speciality. You can hear the band’s patented rave-up technique on the early Clapton material. Normally, the so-called rave-up is instigated in the middle of the song. The verse checks out, and each musician starts playing louder, faster, and on and on and on, until you think the music itself is going to explode, at which point, the rave-up cuts off and the song proper resumes.

“I’m a Man” is as orgastic as anything you’ll ever hear, and on the studio version we get a two man rave-up, almost a rave-up duet with Relf blowing hot harmonica lick, and then Beck responding with a faster guitar solo, which Relf answers, and so on, until Beck starts smashing strings, like he had become hell bent to turn his guitar into a percussion instrument. Fuck the strings, basically.

The rave-ups would continue into the Page era. Well, they weren’t so much in evidence on Little Games, a slice of pop fluff helmed by Mickie Most, who had helped make Herman’s Hermits – a pleasing but twee band – into stars.

The Sole Landmark Yardbirds Album

Discounting the BBC material, there was one bona fide, full-length masterpiece in the entire Yardbirds discography: 1966’s Roger the Engineer.

The LP featured a generous helping of rave-ups, but as people would say to me in used record stores – where the Yardbirds have always been kings and such matters are discussed fervently – if you wanted to experience the true genius of the band, you needed to hear them live. And they didn’t mean on the early Clapton material, or even the BBC tracks, where Beck did things on the guitar that Hendrix couldn’t better, on those same airwaves, a year later. Nope. You needed to have heard them in some sweaty beat club, or a now long gone auditorium, where the Yardbirds, simply, shredded, and shredded like no one ever had before.

The LP featured a generous helping of rave-ups, but as people would say to me in used record stores – where the Yardbirds have always been kings and such matters are discussed fervently – if you wanted to experience the true genius of the band, you needed to hear them live. And they didn’t mean on the early Clapton material, or even the BBC tracks, where Beck did things on the guitar that Hendrix couldn’t better, on those same airwaves, a year later. Nope. You needed to have heard them in some sweaty beat club, or a now long gone auditorium, where the Yardbirds, simply, shredded, and shredded like no one ever had before.

Related: Making sense of the Yardbirds’ album releases

Glimpses provides plenty of examples of such shredding across a range of settings. There are numerous takes on “I’m a Man,” with one of the rawest coming from the fifth English National Jazz & Blues Festival in summer 1965. This was an English gig, and I remember watching the video back in my mid-teens.

Relf was all nose in his vocals; that is, he might as well been singing through it, such was the twang of his voice, which was oddly and pleasingly, sinister but beckoning at the same time. I loved how he didn’t give a damn that he didn’t sing in a traditional manner, and one can imagine all of the eventual punk rockers who heard Relf and heard fresh possibilities open up to them. His life was cut short on May 14, 1976, at just 33.

Taking Blues-Rock Into the Stratosphere

“I Wish You Would” – which had been the band’s first single back in the Clapton days – starts in medias res – that’s Latin for “in the middle of everything,” kids – on the National Jazz & Blues Festival tape, making it sound all the more interplanetary. Clapton riffed hard on the song, both in the studio and on a 1963 Crawdaddy Club date. But whereas Clapton’s playing was measured, like he was trying to work himself into a tradition of electric bluesman like Elmore James, Buddy Guy and Freddie King, Beck has no interest in a tradition save the one he might be starting in that very moment. The riff is made up of serrated lines, and you start to wonder if this music is somehow about to become physical and capable of scoring flesh.

Another version of “I Wish You Would” dates to a June 1965 gig in Paris, when the Yardbirds opened for the Beatles. They must have sensed a battle of the bands element at play, and while I’ve never been able to find anything but this one song from their set, it’s louder and punchier on Glimpses than it’s ever been on any bootleg I have heard. The rapidity of Beck’s playing is almost disorienting, and Relf riffs right along with him, on harmonica punctuating the intervals with those beguiling vocals of his.

The BBC cuts have always been in good fidelity, but they’ve been burnished some more for this package, and while they’re not often as intense as the material that was cut in front of an audience – even though they are, strictly speaking, live – it’s rather remarkable that the clutch of “lost” Beeb cuts presented on Glimpses possess something more endemically Yardbirdsian than any other material on the set.

The fidelity is rougher, scrappier, like they been recorded by a schoolboy with a tape recorder pressed up to the radio, which may be what happened. There is a remarkable rendition of “Jeff’s Boogie,” which I’d number as one of the premier guitar cuts ever recorded, however unprofessionally. One might think of it as a guitar epic in miniature, akin to a condensed version of something like Hendrix’s Woodstock take on “The Star-Spangled Banner” or the famous Fillmore East rendition of “Machine Gun.”

The Beck material leads into a number of sessions with Jimmy Page on lead guitar. If you’re a Led Zeppelin buff, this is the stuff for you, with songs and arrangements that would feature in the early phase of the Zep’s career. Personally, I’ve always thought of Zeppelin as a much more cumbersome, lumbering version of the Yardbirds, without the nuance, humor and panache. The Yardbirds were liquid-y and pliable; Zeppelin, brittle and metallic.

A/B-ing any of the live Yardbirds versions of “Dazed and Confused” with one by Zeppelin will give you some idea. There’s more mystery to be had with any of the Yardbirds cuts, while Zeppelin is all out in the open, bashing away, throttling you with the riff. The Yardbirds, meanwhile, seem to be trying to haunt you with it, and, in large part, they succeed, even if this iteration of the band had no intention of innovating like the Jeff Beck one did.

You wonder what must have been going through Jimmy Page’s head when he first joined the group, on bass, and Jeff Beck was already deep in what I’d argue was the most significant phase – in terms of influence – for any guitarist since Robert Johnson and before Jimi Hendrix. One of my favorite performances here comes from Paris, but in the summer of 1966 this time. “The Train Kept A-Rollin’” was always one of the most exciting Yardbirds numbers, which is saying something.

Beck kicks off the song by imitating a train whistle with his guitar, and then serves up the crunchiest, filthiest riff. The distortion thrilled me as a kid, as I thought, “wait – can you do that? Is that allowed?” Just dead brilliant. This particular version is faster than its studio counterpart, and because of the guitar, the lyric – which is putatively about lighting out on the rails – is transformed, in the best Yardbirds style, to suggest that here is a force beyond this world, hell bent upon altering it at the same time. “Train kept a’rollin all night long,” Relf declares, as Beck riffs, and you realize that, to the band, anyway, the Yardbirds are the train, and the night is limitless. They were probably on to something there.

The Yardbirds’ recordings are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Pete Townshend: 10 Great Guitar Solos With The Who - 05/19/2024

- Digging In to The Yardbirds History - 05/12/2024

- 10 Great Classic Rock Live Bootlegs - 05/11/2024

10 Comments

It was their manager Simon Napier-Bell who made the comment that there were only 4 rock bands on the planet worth managing…and one of them was The Yardbirds.

Russ – What were the three other bands?

He has managed: Ultravox, T Rex, Marc Bolan, Japan, Asia, Candi Staton, Boney M, and Wham!

You failed to mention the album they did with Jimmy Page-Little Games.

Great article. I see by the comments it was published awhile ago. Little Games is mentioned in there so I’m not sure what the above poster was reading. Growing up I was first into Zeppelin. Cream and the Jeff Beck group before the Yardbirds but certainly went back and learned my share of where all the guitar gods came from. The film Blow Up also really upped my interest in the band. I happened to catch Blow up 3 times in the last year on cable and I still love seeing the movie every time as its a great film with or without the band. It’s awesome to see Beck go bonkers in it as Page smiles and keeps on playing. To this day Beck is still my all around favorite guitar player along with John McLaughlin. Though I have plenty of American guitar greats I’d have to put up there as close seconds like Duane Allman, Jerry Garcia, Jimi etc. This article really makes me wanna go seek out those live BBC sessions so I’m looking them up later on YouTube. Thanks for a great read.

No mention of The Yardbirds 1st guitarist. ..Tony Top Topham …???

Nice write-up, Colin. I’m assuming you have the Chris May/Tim Phillips book “British Beat.” My sister gave me a copy when I was 13. Somewhat dog-eared now, it’s still an indispensable part of my library to this day.

I don’t currently care too much about Yardbirds’ music per se, but would have been fun to be at their gig, the feeling, the excitement, the dancing.

I was reading along just fine until the “f” word.

Surely a substitute word could’ve been used to

accent/describe what you were trying to say.

Keep it clean please (use at least 60% isopropyl)

The 1966 LP is NOT titled “Roger the Engineer”, but “Yardbirds”. On the jacket, spine and record label.

The YARDBIRDS wiith the Electricity of the Band Being Keith Relf, VOCALS/Harmonica in Intro of Songs. The YARDBIRDS would Not be Complete without the Guitar Fretting of the Three Guitar KINGS…

Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck who ALL Moved On to their Own Individual Success Stories… Everyone Needs to Listen to their Talent in Hearing.. “The Train Kept A-Rollin'” and

“I’m a Man”. DOESN’T GET ANY BETTER!!!