Not many rock bands can sustain decades of commercial success without personnel changes. Like most love affairs or marriages, the relationship dynamics between creative musicians alter with the years; what were minor personal or aesthetic irritations in early times can become full-blown “deal-breakers” and “artistic differences” later. What worked in the days of scuffling for gigs and trying to get a record contract often doesn’t when the hit records, world tours and big money start to roll in. For the celebrated British prog-rock group, Yes, changes in their lineup were seemingly built into their DNA.

Not many rock bands can sustain decades of commercial success without personnel changes. Like most love affairs or marriages, the relationship dynamics between creative musicians alter with the years; what were minor personal or aesthetic irritations in early times can become full-blown “deal-breakers” and “artistic differences” later. What worked in the days of scuffling for gigs and trying to get a record contract often doesn’t when the hit records, world tours and big money start to roll in. For the celebrated British prog-rock group, Yes, changes in their lineup were seemingly built into their DNA.

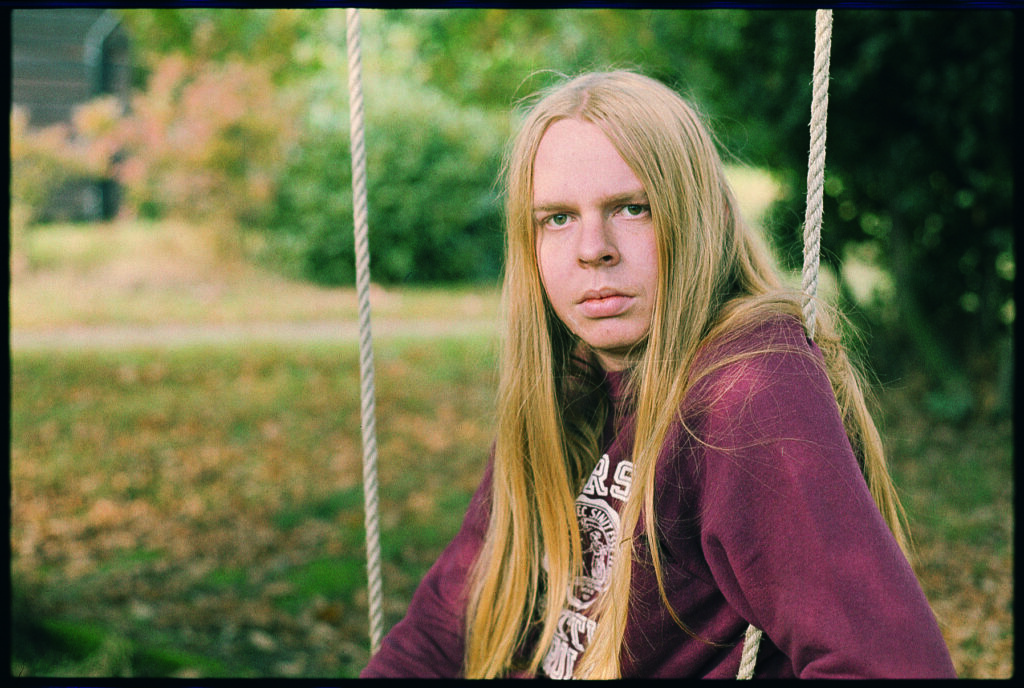

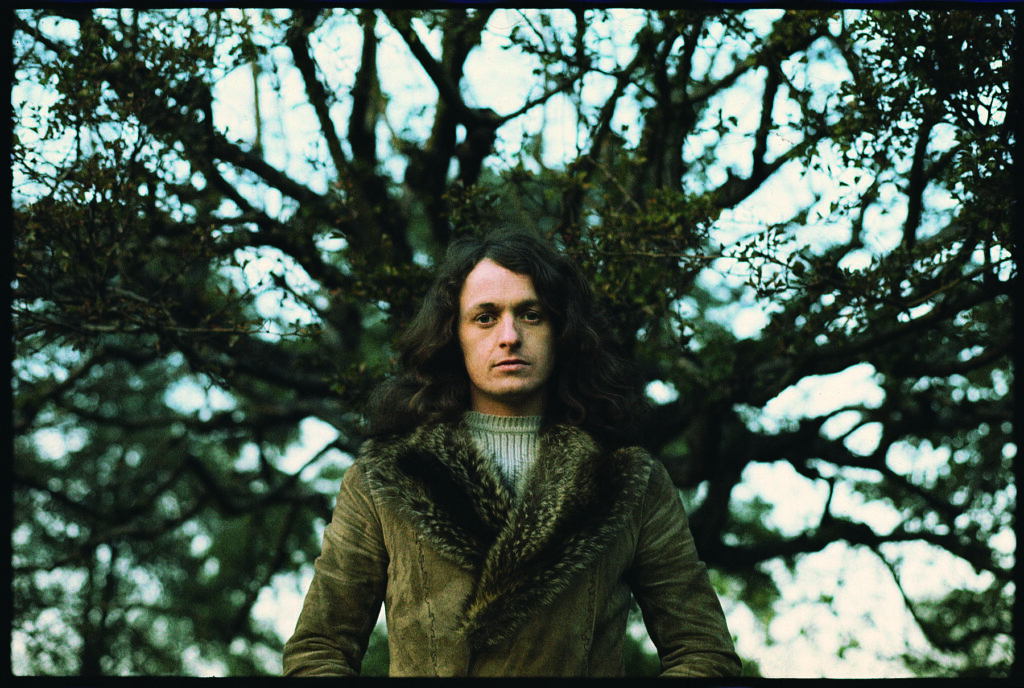

Formed by singer Jon Anderson, bassist Chris Squire, keyboardist Tony Kaye, guitarist Peter Banks and drummer Bill Bruford in 1968, they released two LPs on Atlantic Records before Banks was out and Steve Howe in for The Yes Album, their breakthrough disc, in early 1971. Yes intended to produce their follow-up with the same musicians, but Kaye reportedly balked at expanding the keyboard sound beyond his comfort zone (Hammond B-3 organ and piano), and the more adventurous Rick Wakeman was recruited after they’d already started work on the album that became their second big hit, Fragile.

Wakeman had done stellar work as a member of the folk-rock group Strawbs, and was a go-to session man who had to turn down an offer to join David Bowie’s band in order to throw in with Yes. Classically trained, Wakeman was excited by the Moog and ARP synthesizers, Mellotron and electric piano he’d added to his keyboard arsenal.

As Anderson told Penny Valentine from Sounds at the time, “I do feel we should produce an album now that will really make our position firm. I still feel that we’re not really as established as we could be—we’ve been able to play better places, we’ve been able to make our first tour of the States and all this has contributed to us becoming better known—but this album now is something of a responsibility…before we did The Yes Album we had two months to really sort out the basic ideas. This time there just hasn’t been that time and we’re still getting over the obstacles of making an album that will entertain.”

Indeed, the original idea of producing a double-LP combining live and studio tracks was ditched, and recording with Atlantic’s Tom Dowd in Miami didn’t pan out either. Instead, Yes hunkered down in London during the summer of 1971, using Advision Studios and their familiar engineer Eddie Offord as co-producer.

Pressed for time in the studio before another U.S. tour, the commercially savvy Anderson worried: “There is always a danger with any band where the musicianship is so good, that you do things that are basically showing off and lose track of the people that are going to hear an album and get satisfaction from it.”

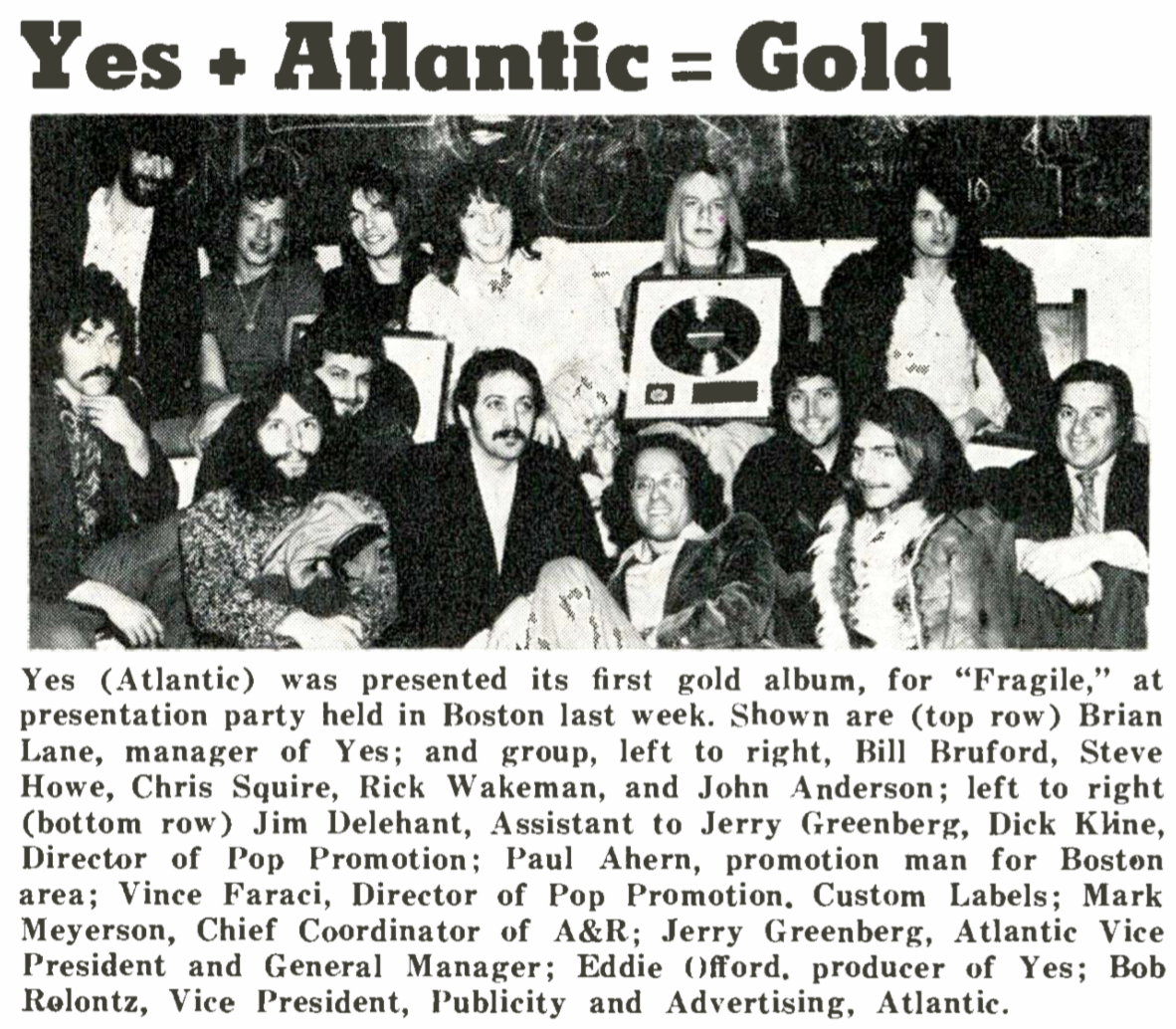

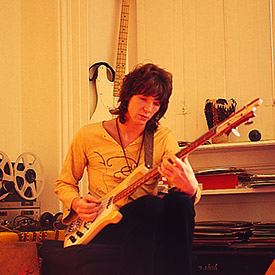

Fragile eventually included a number of “solo” pieces, with each member responsible for helming a short contribution. Even after the LP—released in November 1971 in the U.K. and Jan. 7, 1972, in the U.S.—was a hit, reaching #4 in the American Billboard album chart, Squire told journalist David Hughes, “I’d agree with people who knocked us for the solo pieces, but in a way you’ve got to appreciate the circumstances. We had to get another album out quickly from a purely financial point of view. We have a lot of mouths to feed, Rick had to buy a vast amount of new equipment when he joined, and it all costs much more money than people seem to imagine.”

“We tend to try and spend as long a time as possible working on album material,” Squire continued, “but again this just wasn’t possible, particularly as we had already spent so much time and effort on [11-minute track] ‘Heart of the Sunrise’. So we opted for the solos, which were easier to rehearse and record.”

Fragile begins with the phantasmagoric “Roundabout,” which in edited 45 rpm form hit #13 on Billboard’s Hot 100 and became one of Yes’ signature tunes. The full 8:30 is a travelogue of intriguing musical ideas, so expansive it seems impossible only five musicians perform it all. Based on Howe’s original instrumental “guitar suite,” Anderson worked it into a real song, with joyous lyrics that tantalize with trippy imagery: “In and around the lake/Mountains come out of the sky and they stand there/One mile over we’ll be there and we’ll see you/Ten true summers we’ll be there and laughing too.”

The dramatic intro features two pianos played backwards and Howe’s expert flamenco stylings. (He’s one of the few great electric guitarists who don’t lose anything switching to acoustic.) Squire plays what amounts to a propulsive “lead bass,” and Wakeman colors with a rushing swirl of keyboards, background and foreground in the deeply layered mix. Time signatures change, Bruford never falters on basic kit or expanded percussion, and complex multi-tracked vocals are captured expertly by Offord. The slow interlude at five minutes is magical, and yields to an aggressive Hammond B-3 workout from Wakeman, and another series of snaking electric guitar parts that somehow combine Wes Montgomery and Jimi Hendrix. Howe favored hollow-bodied electric guitars like the Gibson ES-175 and ES-5 Switchmaster, giving him a jazzier sonic signature.

Wakeman said it took him 15 hours to record all the parts for “Cans and Brahms,” his adaptation of material from the third movement of Brahms’ 4th Symphony, for electric and grand piano, harpsichord and synth. Unable to supply his own compositions due to a publishing dispute (he was still signed to Strawbs’ label A&M as a solo act), he turned to his classical background here. Apparently he’s always been perturbed he was never paid or credited for his part in co-writing other Fragile tracks. (Wakeman also later said he was surprised how much arguing the group did in the studio as they worked up arrangements; he slowly realized their touchiness led to some rigorous music indeed, and he learned to fit in and shut up about money.)

In Tim Morse’s Yesstories book Anderson called the brief “We Have Heaven” “a rolling idea of voices and things.” It’s an impressive roundelay which yields to the eight-minute “South Side of the Sky,” written by Anderson and Squire (and the unlisted Wakeman). Each member contributes at the top of their virtuosity, from Bruford’s ever-surprising offbeats, Wakeman’s authoritative grand piano, and the stacked Anderson-Squire-Howe vocals. At 5:30, a muscular, pounding section with Howe’s electric juxtaposed with Anderson’s high keen is a Led Zep-level cruncher. Howe’s concluding solo is one of his best. It fades into the sound of (synth) wind that began the track, ending side one.

Side two of the original LP begins with a very quick Bruford-penned intro titled “Five Per Cent for Nothing” before another Yes classic, “Long Distance Runaround,” kicks in. Although it might not be obvious, Anderson told journalist Carl Wiser he wrote the lyrics as both a critique of religion and a commentary on the shooting of students at Kent State: “I still remember the dream there/I still remember the time you said goodbye/Did we really tell lies/Letting in the sunshine” and “Cold summer listening/Hot color melting the anger to stone” are perhaps the lines that gesture in that direction.

“Long Distance Runaround” is quintessential Yes, combining delicate effects with powerful counter-streams. Howe’s jazzy dual-guitar figures open the track, quickly joined by Squire’s dominating bass. Listen to how masterfully Bruford takes his punctuation cues from both of them, finding a middle ground of support. The tempo and atmosphere change with Anderson’s entry at forty-five seconds in, as the track becomes positively poppy, and Wakeman’s piano provides a deceptively simple doo-wop accompaniment. For anyone critical of prog-rock’s experimental bona-fides, “Long Distance Runaround” is a cogent rebuttal: pithy, fun and always surprising.

If King Crimson’s Robert Fripp listened to Fragile, perhaps this cut suggested Bruford’s sly touch with percussion—what was once called his “unusual beat placement”—could fit into Crimson, which is indeed where Bruford fled the following year after getting fed up with Anderson, Squire and Howe’s constant bickering.

Related: Our Album Rewind of The Yes Album

Howe’s concluding Echoplex effect leads into Squire’s piece “The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus),” an Afro-funky one-man jam with a dazzling array of interlocking effects, with (as the album credits note) “each riff, rhythm and melody” produced by Squire on sonically manipulated basses. Anderson intones the eight-syllable Latin name of a marine creature, and there might even be some percussion by Bruford in there too.

Playing a Conde flamenco guitar, Howe performs his lovely solo instrumental “Mood for a Day” before the epic “Heart of the Sunrise,” credited to Anderson, Squire and Bruford, finishes the album. It begins with a bang, Bruford and Squire especially giving a master class, before Wakeman’s eerie mellotron puts a wide screen behind them. There’s more than a hint of the stop-start Fripp riffing of “21st Century Schizoid Man” in the first three minutes of “Heart of the Sunrise,” but Anderson’s gorgeously breathy entry with “Love comes to you and you follow,” as Howe provides delicate support, takes it in a different direction.

Wakeman’s keyboards at the six-minute mark are part of his excellent melodic additions, and by the time Anderson sings “Straight light moving and removing/Sharpness of the color sunshine,” every Yes member has had multiple moments to shine. Wakeman brings a classical structure to the track, with recapitulations of different themes circling back. The whole piece ends on an upbeat that creates an immediate anticipation of whatever Yes might have up their sleeves next. (It turned out to be Close to the Edge, an album that doubled-down on prog-rock, consisting of only three tracks, including the title cut, which runs nearly 19 minutes.)

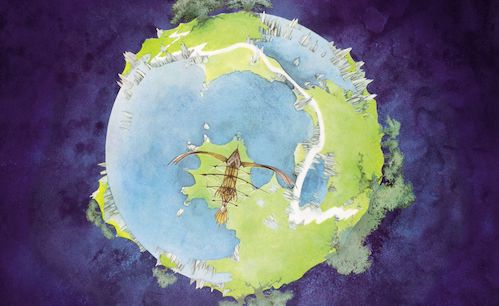

Speaking of sleeves, the album cover was the first produced for Yes by Roger Dean, who would design their logo, stage sets and posters for decades. His painting of a “fragile bonsai world” was partially based on his perception of the collective personality of the band (Bruford supposedly called them “breakable”). Others have suggested the album was titled by their manager Brian Lane, who noticed the stenciled “FRAGILE” in photos of their stage equipment. In any case, Dean’s mythological visions of outer and inner space put into optical form some of the eclecticism and wonder of Yes’ music.

After many more hits and lineup convulsions, Yes was finally inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2017, with only some of their 20-plus members officially recognized: Anderson, Howe, Squire, Wakeman, Kaye, Bruford, drummer Alan White (1972-1981, 1983-2022) and guitarist Trevor Rabin (1983-1995). Sadly, Squire had died in 2015.

Mirror to the Sky, Yes’ 23rd studio album, was released in May 2023. The group is now led by Howe and Geoff Downes, who’d first joined Yes in 1980, one of those who’ve come and gone and come back over the years. Their lead singer is Jon Davison, although Jon Anderson (who toured playing Yes music with Rabin and Wakeman from 2016 to 2020) recently told Rolling Stone, “In my mind…I’m still in Yes.”

[Yes’ extensive discography is available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.]

Watch Yes perform “Roundabout” live in 1972

- Patti Smith’s ‘Horses’: Poetry In Motion - 05/21/2024

- Elton John ‘Honky Chateau’: New Heights - 05/19/2024

- Paul Simon ‘There Goes Rhymin’ Simon’: American Tunes - 05/05/2024

2 Comments

My favorite band of all time. Such epic sweeping music that takes you on a journey. Not my favorite of their collection, but a defining album for certain with Roundabout being their crowning glory stateside. Rotation of members usually adding to their creative genius, as many as there were.

I’m glad that “Yes Album” and “Fragile” and “Close to the Edge” were released in 5.1 a few years ago. Two channels just couldn’t contain everything.