If asked to sum up The Yardbirds in one sentence, most rock fans would probably say something like this: They introduced the world to Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page.

That is true, they did. Each of the three renowned guitarists first achieved international recognition while a member of the blues-rooted British Invasion band, which existed for a mere five years, 1963-68, but exerted an outsized impact on rock.

Clapton replaced the band’s original—and still basically unknown—guitarist, Top Topham, shortly after its birth, in October 1963. Frustrated with their musical direction, Clapton then bolted in March 1965, relinquishing his spot to Beck, who lasted until November 1966, at which time Page, who’d first joined the group as its bassist in June 1966 (and, for a brief period that summer, doubled up with Beck on guitar), took over the lead guitar spot. Page stayed on until July 1968, when he went off to start a new band with some fellows named Plant, Jones and Bonham, but that’s another story for another article.

The above paragraph tells a very abbreviated tale that, if the details were to be expanded, would easily take up several more pages, and has filled several books. (You can read one extended take on it here.) Other personnel changes took place along the way, with only lead vocalist Keith Relf, rhythm guitarist Chris Dreja and drummer Jim McCarty serving throughout the entire run. There were hit singles (“For Your Love,” “Heart Full of Soul,” “Shapes of Things”), equally superb not-so-hit singles (“Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” “Little Games”) and a handful of very different but mostly slapped-together albums. They’re all worth considering, but there’s no denying that the Yardbirds’ recorded legacy was just as convoluted as their personnel timeline, with few correlations between their American and British output.

Let’s back up again. Putting aside their U.K. and U.S. singles releases, the band’s album releases were relatively straightforward for a few years, if ill-reasoned. In December 1964, the lineup with Clapton on guitar (and Paul Samwell-Smith on bass) released Five Live Yardbirds, their debut LP, in the U.K., on Columbia Records. That album, not released in America at the time, was all about the blues and R&B: There are no original compositions on it, only covers written by the likes of Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, the Isley Brothers, John Lee Hooker and Howlin’ Wolf. Recorded at the Marquee Club in London in March 1964, around the time that the Beatles were first breaking in the U.S., this is the stuff that made Clapton’s mouth water, and he shines on it.

Listen to “Five Long Years” from Five Live Yardbirds

Not that anyone noticed: The album did not get an American release, plus it failed to chart at home. The Yardbirds may have been one of the hottest blues-rock bands in Britain, but few knew. They wouldn’t even release another LP in their homeland until well into 1966 (we’ll get to that momentarily).

Related: In 1966, the Yardbirds appeared in the Antonioni film Blow-Up, with the Beck-Page lineup

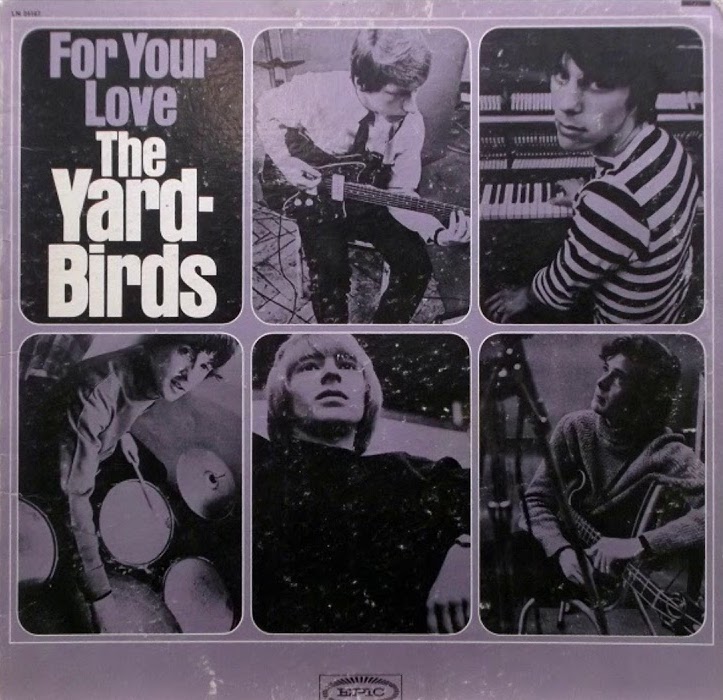

In the meantime, there would be two U.S. LPs that did not get British releases. First, in July ’65, came For Your Love, composed nearly entirely of covers, save for one Relf original, “I Ain’t Done Wrong.” The title track, penned by Graham Gouldman, featured Clapton on lead guitar and gave the band its first, and biggest, American hit single, reaching #6 in the spring of 1965.

By the time it took off though, Clapton had already vacated, pursuing his blues jones with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and then, in 1966, Cream, the band that would elevate his status so considerably that some fans took to painting the words “Clapton is God” on London walls.

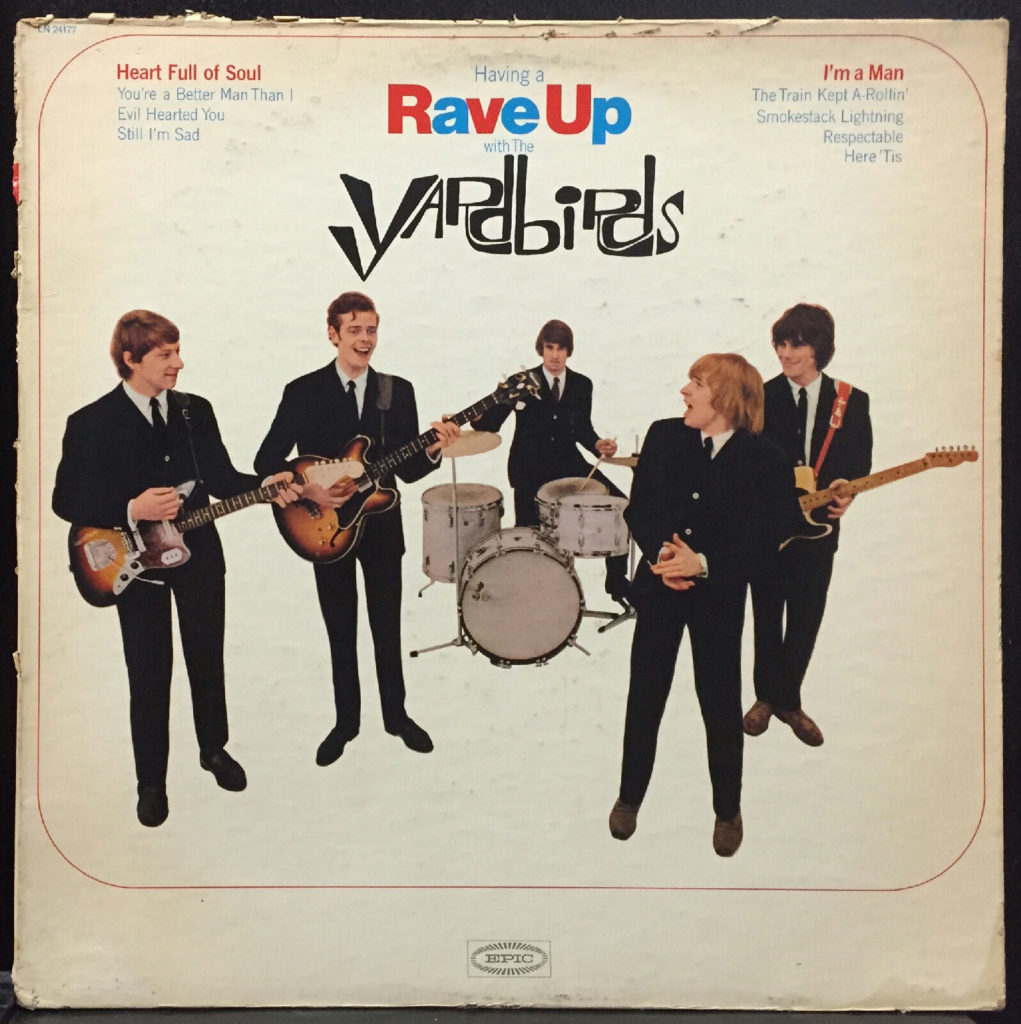

Beck was already entrenched when the For Your Love LP was released on Epic Records in America, and in fact plays lead guitar on three of its tracks. Still, when American fans were offered Having a Rave Up With the Yardbirds, in November 1965, they had every reason to believe that Clapton was still, in some manner, a presence, as he occupied the entirety of side two of the album, recorded live in ’64. Consisting of four covers, the Clapton tracks offer a formidable farewell, but the future direction of the Yardbirds was much more easily discerned by playing side one, all of it featuring Beck. Although there is only one original tune, “Still I’m Sad,” credited to Samwell-Smith and McCarty, there are strong indications—particularly on the two Gouldman compositions, “Evil Hearted You” and the top 10 single “Heart Full of Soul”—of the more experimental pop-oriented direction the band would take. Other tunes on Rave Up, notably Mike Hugg’s “You’re a Better Man Than I,” are some of the Yardbirds’ best, and again point away from the blues.

Related: Our interview with Graham Gouldman

By 1966, things had begun to stabilize—somewhat. With Clapton long gone, the quintet of Relf, Beck, Dreja, Samwell-Smith and McCarty was anxious to start joining their contemporaries by recording their own material and dressing it up in the studio with a plethora of styles and sounds. That April, with Samwell-Smith and Simon Napier-Bell co-producing, the band entered a London studio to begin work on their first proper full-length album of all-original material: The entirety of it was credited to all five musicians.

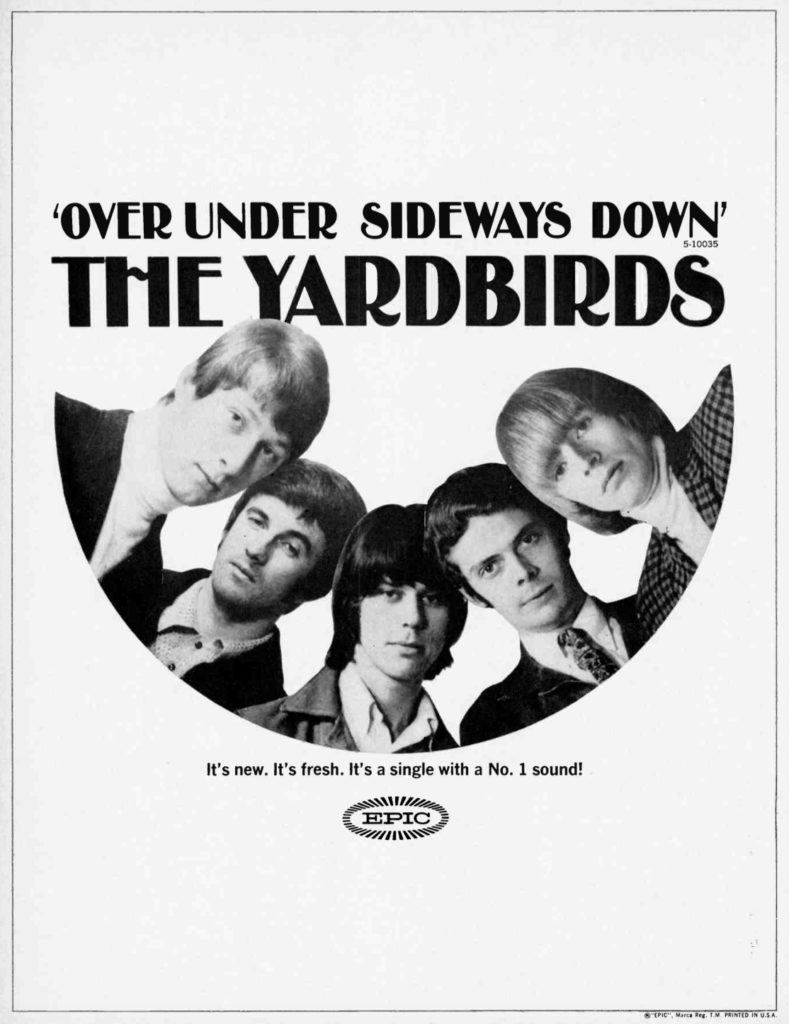

The first two tracks they laid down, “Over Under Sideways Down” and “Jeff’s Boogie,” were released as a single in both England (on May 27, 1966, where it reached #10) and America (#13, a couple of places lower than the extraordinary, non-LP track “Shapes of Things” a few months earlier).

The single revealed a new overtly psychedelic direction for the Yardbirds, with Beck’s Eastern-inspired guitar line displayed prominently, falling into a repeating pattern throughout most of the track, then exploding into a fiery barrage toward the end. Relf’s lead vocal, punctuated by the others’ restated “Hey!” chant, is one of his strongest, the lyrics falling more or less into the then-popular protest category (“When I was young people spoke of immorality/All the things they said were wrong are what I want to be”), a hypnotic tag line (“Over under sideways down, backwards forwards square and round”) breaking up the verses. “Jeff’s Boogie,” meanwhile, is just that, but on overdrive, a precursor to the kind of pyrotechnical madness Jimi Hendrix and others would be proffering shortly.

The two sides of the single were included on the finished album; the rest presented something of a guided tour of the Yardbirds’ growing versatility. The opening track, “Lost Woman,” kicks off with Samwell-Smith and McCarty swinging the intro madly, like a crazed troupe of bebop hepcats, before Beck and his wah-wah begin their total domination of the remainder (his solo is off the charts). The album’s first half also includes “I Can’t Make Your Way,” soul-infused, swaying folk-rocker with stacked vocals; the sing-songy, folkish “Farewell”; and “Hot House of Omagarashid,” little more than an endless volley of “Ya-ya-ya-ya-ya-ya”s chanted African-style while Beck and the others unleash all of the sound effects they discover in the studio. The second half of the set features the fuzz-drenched “He’s Always There”; the airy, proto-prog “Turn Into Earth”; the garage-y “What Do You Want”; and the album-closing “Ever Since the World Began,” at first echoey and mysterious, then switching gears, without notice, toward a modified rockabilly rhythm that Relf rides straight into the song’s abrupt halt.

You’d think that, having issued different albums in America and the U.K. to that point, Columbia and Epic would coordinate and release the same album in each country. But in the crazy, mixed-up world of the Yardbirds’ recording history, that would make too much sense. The U.K. release, not uncommon to the era, featured two tracks not included on the U.S. version: “The Nazz Are Blue” (sung by Beck) and “Rack My Mind,” both tossed onto the first side of the vinyl LP. The U.K. and U.S. editions also featured different mixes.

But not only did the track listings and mixes differ in each country; the albums were given different titles on each side of the Atlantic. And there’s even some confusion over that.

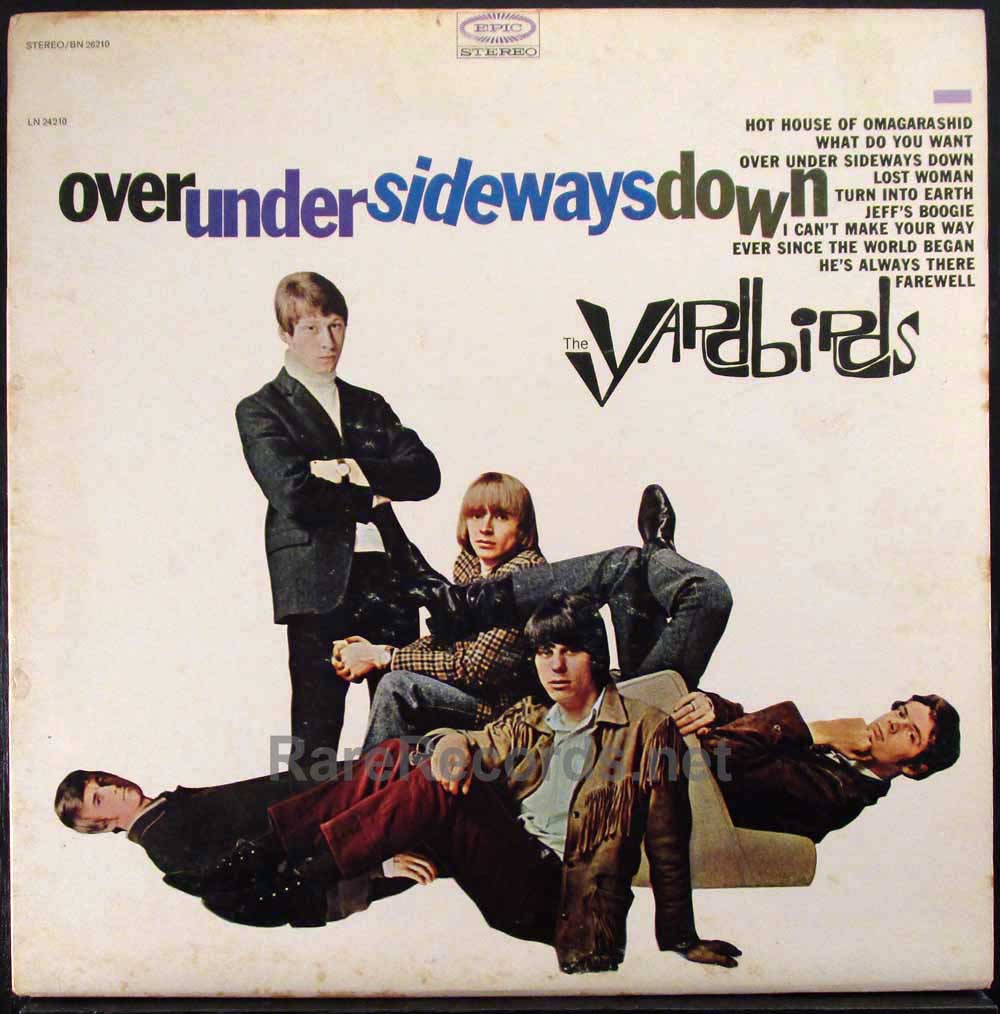

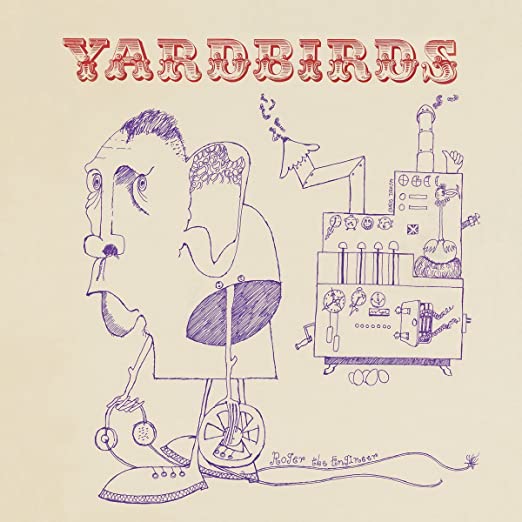

In America the LP, the group’s third in all, was unambiguously titled after the hit single, Over Under Sideways Down. The LP jacket featured a portrait of the five band members in various over-under-sideways-down positions, over a plain white background. In the UK, however, the new album was officially titled Yardbirds, with the band’s name emblazoned across the bottom; the rest of the cover, drawn by Dreja, is a pen-and-ink depiction of the album’s sound engineer Roger Cameron. With the words “Roger the Engineer” positioned subtly toward the bottom of the cover, many U.K. fans simply assumed that the album’s title was Roger the Engineer.

And so it came to pass—as the years chugged on, the album was routinely accepted as Roger the Engineer, and by the time it was re-released in England in 1983 (with two more tracks tacked on, “Psycho Daisies” and “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago”), that’s what it was now called.

There would be one more Yardbirds album in America—1967’s Little Games, recorded as a quartet with Page as the sole guitarist—as well as a briskly selling Greatest Hits collection that gave the band its highest position on the Billboard LP chart, #27. A cheapo cash-in collection, Sonny Boy Williamson and the Yardbirds, recorded in 1963, also found its way to the market in both countries (on labels they were not signed to).

But in the band’s homeland, there was nothing else to speak of: Neither the “Little Games” single nor same-titled album would see a release, and when the band called it quits, few noticed—until, that is, Jimmy Page unveiled his next move.

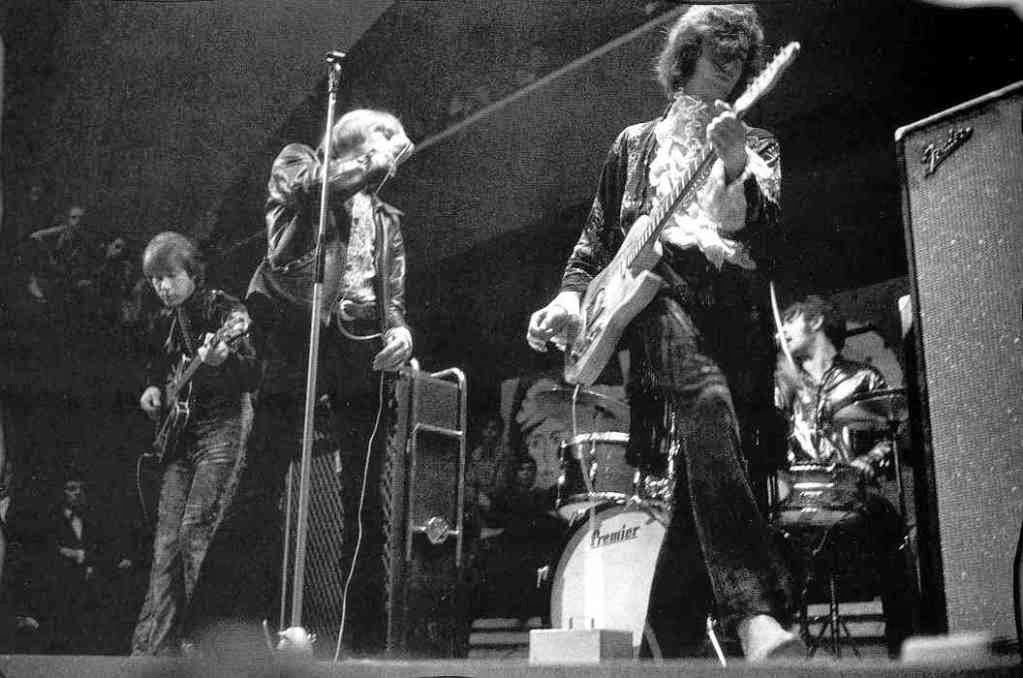

Watch a rare live video from 1966 featuring the Beck-Page lineup

The Yardbirds’ albums and collections are available in the U.S. here and in the U.K. here.

- Over Under Sideways Down: Making Sense of the Yardbirds’ Album Releases - 05/27/2024

- 17 Classic Chuck Berry Covers - 05/18/2024

- ‘Brandy’ by Looking Glass (It’s a Fine Song) - 05/18/2024

5 Comments

Live at the Anderson Theater, ?

Yes, I was going to mention the live album, but it was well after the band broke up to cash in on Zeppelin’s fame, and was quickly recalled when Page threatened to sue.

Indeed Live at the Anderson on 2nd Ave, Manhattan. Was there only about 30 in the audience, Jimmy was jaw dropping good. using the bow on the Tele, popping strings but not missing a note. Shape of real things to come!

as always, nice job, jeff. with the times what they are these days, i had to listen again to “better man than i”. still works.. still speaks…

keep it up!

Thanks!